Kiribati's climate change Catch-22

- Published

Kiribati's fight to survive amid climate change

As world leaders try to hammer out a deal on climate change in Paris, a number of Pacific nations will be watching with interest. The impoverished country of Kiribati is one of them, having little resources to combat the issue. The BBC's Tim McDonald details its dilemma.

Bwebweata Atiana ties his tiny hut to a pandanus tree. Almost every month, the high tide batters the beach next to it.

Water washes all the way up to the main road that runs through his village here on Marakei, a small atoll about a 20-minute flight from Kiribati's main island, Tarawa.

"During the high tide, the waves come and the strong winds and these ropes are to make it steady. To keep it in place during the high tide," he says.

Even by Kiribati's basic standards, it's a rudimentary fix. But the people here have little to work with. And really, that's the problem at the heart of Kiribati's climate dilemma.

Kiribati's President Anote Tong is seriously considering the option of abandoning the country

The notion that Kiribati will sink because of rising sea levels is a narrative that's powerful in its simplicity. But scientists have their doubts. , external

Atolls constantly expand and erode. Storms and tides deposit material on one side of the island even as they wash it away on the other.

If more washes up than washes away, the atolls grow, and Kiribati will rise with the tide. In short, many scientists think the islands will shift rather than sink, and climate change will speed up the process.

President Anote Tong insists that the risk of sinking is real. But he points out that even if it's not, Kiribati will still have great difficulty keeping up, as islands erode in some places and grow in others.

"It doesn't matter, because you can't keep moving houses," says Mr Tong.

The main island of Tarawa is overcrowded and faces sanitation issues

Kiribati faces a Catch-22: it needs to advance economically to defend itself, but sea-level rise is certain to slow or even stop its progress.

It's a dilemma the president struggles with. The option of abandoning the country altogether is squarely on the table, although he still holds out hope.

"There is no doubt in my mind that it is doable. But I think where the doubt is, will the resources required be available," he says.

At the moment, the answer appears to be no.

The only significant industry here is fishing, and even then, an alarmingly small amount of the wealth that it generates stays in the country.

The World Bank puts per capita GDP at about $1,500 (£996), which is below Laos and Zambia. Add to that high infant mortality rates, a dearth of university graduates, unemployment that tops 30% and slapdash infrastructure.

The Kiribati atolls rely on sandbags - filled from the beach - to construct some seawalls

Water crisis

Life is simple on Marakei, the ring-shaped atoll where Mr Atiana lives, but it's becoming more difficult.

Those who cut toddy (sap from the palm leaves) are losing trees to high tides and erosion. Others who grow giant taro in ponds known as bwaibai pits worry about salinity.

Mr Atiana drinks a handful from one and spits it out again to demonstrate.

Bwebweata Atiana is one of many I-Kiribati worried about the rising salinity of bwaibai pits used to grow food

Down the road at the Kiribati Uniting Church, Pastor Teieka Iaabeitie says his flock sees the changes, and they worry.

"The people here are afraid. The effects of the climate change are more dangerous to our community. Because in our village, more people live in the coastal area, but the high tides are [higher than they were] years ago." he says.

A few reject climate change, or at least the threat it poses, saying the Bible lays it out in black and white. After the great flood, God told Noah that "neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of a flood; neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth".

But if that prophecy is true, there's a loophole.

Because Kiribati might become unliveable, even if it never goes under. The great fear is there could be mass migration to Tarawa, the main island, and the fragile, already-stressed environment there could collapse.

Many in Tarawa worry about more migrating over from other islands

The UN says, external more than 70% of households in Kiribati and Tuvalu would consider leaving home if droughts, sea level rise or floods get worse. In Kiribati most would end up in Tarawa, and the population there could grow by 72%.

That's a huge problem for the water supply, which is already under immense pressure.

Tarawa's groundwater sits a little more than a metre below the surface. On an overcrowded island where everyone has pigs and dogs, and open defecation is still a problem, that means it's contaminated to the point of being undrinkable.

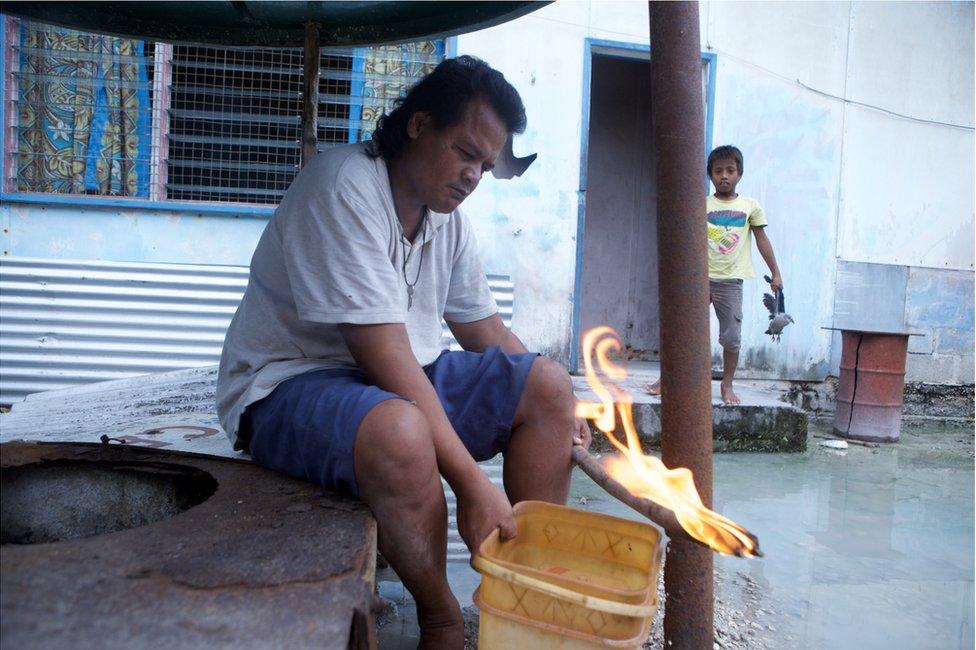

One man, who lives next to a fuel depot, can even set his water on fire, because it's so contaminated with petrol. The depot told the BBC it was unaware of the problem, and it didn't know of any leaks.

The man demonstrated the flammability of groundwater by dipping a stick in water and setting it on fire

A report commissioned by the New Zealand government suggests Tarawa might run dry, as the water supply won't keep up with the population growth.

Already, many people are down to rainwater only, and during a dry spell they have trouble getting enough. Desalination is an option, but public servants say there aren't enough skilled personnel to keep it working properly.

One estimate puts the coastal protection, external alone at about $2bn, which is roughly four times the country's GDP. And money that's spent on seawalls can't be spent on health, education, new business or indeed fixing the water system.

Some countries have found a climate change silver lining in the form of a renewables industry, for example.

But patching up seawalls does little to generate new streams of income or build new skills. It's often a dead loss, and the walls themselves are almost always a temporary fix.

Seawall irony

"Look at this! How many more years will we build these things. How much more money will we spend and waste that we will build these seawalls?" says Claire Anterea from the Kiribati Climate Action Network.

"This is a very big question for us, and I think we will come to the stage that we can't build more seawalls around the place."

She's sitting atop a seawall that collapsed during a monthly high tide, and destroyed a large community hall. This kind of damage is extremely common.

This shipwreck washed onto a seawall during a high tide earlier this year

And it's a terrible irony that the seawalls themselves often contribute to erosion - because they're made from sandbags filled from the beach.

Local factors like poorly engineered causeways and sloppy land reclamation also affect the tides here, and at the moment they're a more significant problem than climate change.

But the tides are a harbinger too. They're likely to get worse with sea-level rise, and changes in weather patterns could add to the problem.

On islands that are just a few hundred metres wide and just a few metres above sea level, it's abundantly clear why people are worried.

"It's happening faster than I thought it would happen. I mean Cyclone Pam that hit Vanuatu hit our southern islands. We don't have cyclones, or we thought we didn't and that is a change in the weather pattern, and that might be a more immediate danger than the sea-level rise," says President Tong.

Tarawans have to constantly patch up seawalls after high tides cause them to collapse

He's not giving up hope though. He points to the Netherlands, a country that's densely populated and mostly below sea level, as an example of a country that has overcome its vulnerabilities.

It aspires to coastal defences that can protect against weather events so severe they're only likely to occur once every 10,000 years.

But like most wealthy countries, the Netherlands has everything Kiribati lacks.

Recently, these pictures, external did the rounds on social media, purporting to show what London, New York, Sydney and Shanghai would look like with after the sea level rise caused by two or four degrees. Engineers have their doubts.

"Flooding of this severity in major cities that are economically important and densely populated is highly unlikely due to the level of protection that is already in place, or would be built in the face of rapid sea-level rise," says climate and environmental risks professor Jim Hall of Oxford University.

Kiribati, by contrast, is a nation of amateur civil engineers, without the skills, materials or money they need - forever locked in battle with the ocean.

- Published5 November 2015

- Published24 November 2015