North Korea 'H-bomb test': What do we know?

- Published

Seismic data from the blast will be analysed further in the coming days and weeks

North Korea says it has carried out an underground test of a hydrogen bomb, a more powerful weapon than the atomic bombs it has tested before.

The BBC spoke to nuclear and defence experts Ankit Panda, James Acton and Bruce Bennett about the latest test.

What do we know about this bomb?

At this stage, not a lot. The United States Geological Survey did say it generated seismic waves equivalent to a 5.1 magnitude earthquake, external, although analysts at the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) said it was equivalent to a 4.9 quake.

Working out exactly how powerful the blast was - also known as its "yield" - depends partly on how deep underground the test was.

Initial estimates have been in the 10 to 15 kiloton range, according to Bruce Bennett, a senior defence analyst at the Rand Corporation, making it just slightly larger than the 2013 test.

However, some reports say the yield was smaller.

What has North Korea tested in the past?

North Korea's tests in 2006 and 2009 are thought to have been plutonium fission devices, but speculation was rife that its 2013 test was of an uranium-enriched device, though this has never been confirmed.

"In general, uranium devices are much more difficult to fabricate and operate," says Ankit Panda, associate editor of The Diplomat.

A test based on a uranium device would spell new dangers because weapons-grade plutonium enrichment happens in large facilities that are easier to spot and uranium enrichment uses many, possibly small, centrifuges that can be hidden away.

North Korea has also depleted its stocks of weapons-grade plutonium but has plentiful reserves of uranium ore.

Whatever your starting material, the significance of an H-bomb is that it is more powerful and technologically advanced than atomic weapons, such as those that devastated two Japanese cities in World War II.

H-bombs use fusion - the merging of atoms - to unleash massive amounts of energy, whereas atomic bombs use nuclear fission, or the splitting of atoms.

Pyongyang residents watch news of the test outside a railway station in the capital

So was this really an H-bomb?

The estimated size of the blast suggests that they did not succeed in detonating a full thermonuclear device, experts say, because in that case you would expect a blast closer to 100 kilotons or more.

"It tentatively appears too small to be a hydrogen bomb," James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told the BBC.

Depending on the depth of the test, it is possible this explosion was partially "boosted", meaning it may have used a small amount of nuclear fusion.

Bruce Bennett says that if it was a full thermonuclear device, it should have generated a seismic measurement of "around seven on the earthquake scale".

When will we know more?

One way to know with more certainty what was detonated would be if radioactive material is released from the test site and picked up in atmospheric samples.

The US will fly its WC-135 Constant Phoenix aircraft to analyse the atmosphere off the North Korean coast. Other countries will also perform their own sampling, "but there is no guarantee that anything will leak," Mr Acton said.

Meanwhile more detailed seismic analysis, by the CTBTO and others, should give a clearer idea of the test's depth and power.

Results may come out in days or weeks. But we may never have a perfectly clear picture of what was tested and how well it went. After the 2013 test, for example, the CTBTO says it detected some radiation 55 days later. , external

The news generated similar interest outside a railway station in South Korea's capital too

What can we say about the significance of this test?

Even if North Korea failed to successfully detonate an H-bomb, the test shows its nuclear programme is continuing apace, a worry for most observers.

If it has indeed tested an H-bomb, it would be a significant advancement of its nuclear programme. Either way, it is nakedly advertising its nuclear ambitions. Earlier this year, it restarted its Yongbyon nuclear reactor, which has been the source of the plutonium used in previous tests.

Condemnation has been pouring in, but experts say the reaction of Pyongyang's allies, particularly China, is crucial.

How important is the miniaturisation claim?

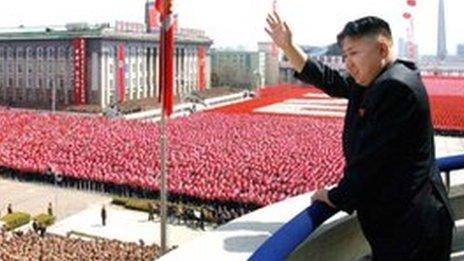

North Korea's leader, shown by state media signing documents related to the test

As in 2013, North Korea, claimed this was a successful test of a miniaturised device.

"Miniaturisation is significant because that is the difference between detonating a nuclear device on the ground and placing it on an inter-continental ballistic missile or a submarine-launched ballistic missile, says Ankit Panda.

If true, it would allowing it to hit neighbouring countries, or potentially even the US. Most experts are sceptical of the claim.

"We really don't know," says Bruce Bennett, who does point out that you can determine the size of an explosion from data, but its design is harder to verify.

Whatever the truth of this test, for diplomacy, observers say it dashes any hopes of North Korea returning to stalled talks involving the US, Russia, China and others.

The BBC spoke to Ankit Panda, associate editor of The Diplomat, James Acton, co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and Bruce Bennett, senior defence analyst at the Rand Corporation.

- Published6 January 2016

- Published3 September 2017