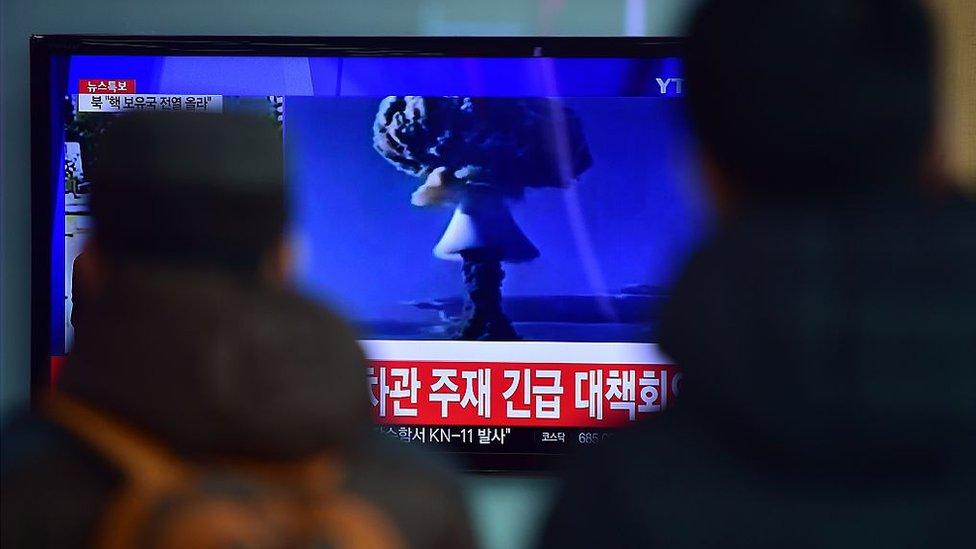

Can North Korea's nuclear expansion be stopped?

- Published

When President Trump (as he will then be) enters the White House, he will have an item flashing as urgent in his email inbox: North Korea. In the election campaign, he offered to sit down with the country's leader Kim Jong-un over a burger, but that generosity seems less likely now.

Eight years ago, when President Obama moved in, the tone was similarly helpful. Right at the start of his tenure, the new president made a gesture of conciliation to the North Korean leader, not quite an offer of friendship but an indication that nose-to-nose threats need not be the way.

In his inaugural address in 2009, President Obama said he would offer an outstretched hand to those who would "unclench their fists".

A few months later, Kim Jong-un responded with the launch of a substantial, multi-stage rocket and an underground explosion of a nuclear device. Both tests were seen by the United Nations as a defiant contravention of the policy of the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Some presidents talk tough but trip over realities. George W Bush said in 2006 that North Korea launching a long-range missile would be "unacceptable" - just before one was launched.

A year earlier, he had said that "a nuclear armed Korea will not be tolerated."

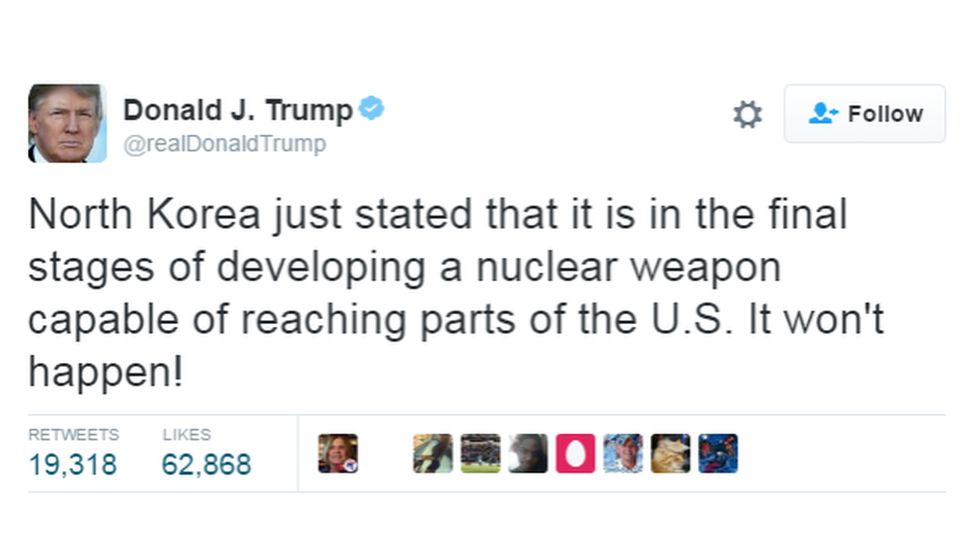

Donald Trump recently tweeted about North Korea's nuclear ambitions

Yet, on all expert estimates, North Korea has made substantial progress in achieving that aim, of having a nuclear arsenal capable of devastating cities in the United States at very short notice. The ability is not there yet but many technology experts think it is getting there.

So the Obama (and Hillary Clinton) policy of strategic patience is giving way to louder talk of military impatience. The doctrine of squeezing North Korea with sanctions and waiting for change is being supplemented by military plans.

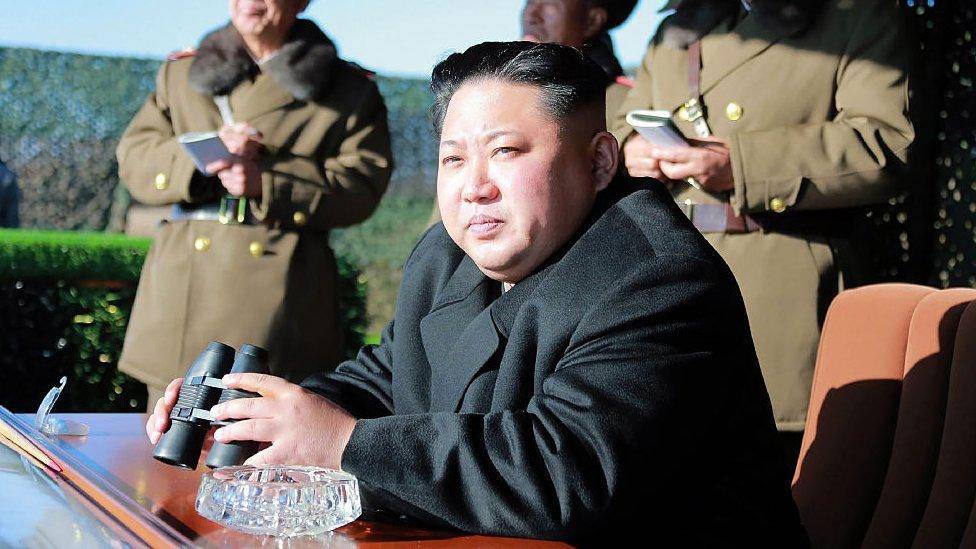

South Korea said it was bringing forward plans to form army units trained to "decapitate" the regime - in plain English, to kill Kim Jong-un. The outgoing secretary of defence in Washington said that any test of a long-range missile which threatened the United States or its allies (South Korea and Japan) would result in it being shot down.

The Pentagon planners are working overtime. But what are the military options?

Not many, is the answer of most experts. Dr Jeffrey Lewis, of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey in California, said that shooting down a test missile fired by North Korea would be very difficult to do and the attempt might lead to massive retaliation by conventional artillery against Seoul, the outskirts of which are within sight of North Korea.

He told the BBC that North Korea's nuclear and missile sites were scattered and that, in any case, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) could be launched from mobile trucks.

Another expert echoed that view. Rodger Baker, an analyst of the region with Stratfor, a global consultancy on geo-politics, said that the trouble with any limited military action against North Korea was that it could easily trigger all-out conflict.

South Korea's capital, Seoul, is within range of North Korean artillery

"They could fire additional short range missiles into South Korea and US military facilities," he explained.

There is similar scepticism about the idea of assassinating Kim Jong-un in the absence of open war. Dr Heather Williams, who lectures at the Defence Studies Department at King's College London, said: "If South Korea pursues this option, they are really playing with fire and might be testing whether or not North Korea really will retaliate - but it would be retaliation against South Korea."

She is annoyed at Mr Trump's tweeting - after Kim Jong-un's assertion that North Korea might get ICBM, the president-elect tweeted: "It won't happen."

Dr Williams added that "so much of nuclear strategy is about signalling and what type of message you are sending. Deterrence is rooted in signalling, so changing from a very carefully-crafted, nuanced nuclear messaging to nuclear messaging in 140 characters is incredibly dangerous."

Much more likely military options than overt aggression, according to the experts, are attempts to slow the nuclear programme by, say, assassinating scientists or inserting viruses into the industry's computer systems (as was apparently done in the case of Iran).

It is worth noting, too, that Iran and North Korea are very different. Iran did not have nuclear devices, whereas North Korea has already detonated five of them and has a well-developed and large testing site (3D images courtesy of the Nuclear Threat Initiative)., external

South Korea says it will form army units to "decapitate" - assassinate - North Korea's leadership

Iran had elections and so the leadership had to take more account of the economic discontent of the people. It had a much more open society, internally and towards the outside world. All this makes the North Korean nut so much harder to crack.

Some experts - and not just from dovish institutions - say that there may come a time soon when the reality of a nuclear North Korea has to be accepted.

Eric Gomez, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute in the United States, told the BBC: "The US long-term goal is de-nuclearisation and that is a noble long-term goal and I think it should remain a long-term goal.

"But, given the status of their nuclear programme now, I just don't think it's a very realistic goal in the immediate term.

"If we can come to the table over some sort of limitation to the current arsenal in terms of delivery systems, that might be the first step towards a larger agreement down the road."

But there are difficulties with that:

Kim Jong-un might not buy it

Japan and South Korea would have to accept a nuclear power on their doorstep, albeit one which could not under a deal expand its arsenal to hit the United States

Mr "It won't happen" Trump might regard accepting a nuclear North Korea as wimpish

It is not a word he likes.

- Published19 July 2023

- Published11 September 2023