How might Donald Trump do a deal with North Korea?

- Published

The world has been consumed by the fear of war in Korea over the past week - everywhere, it seems, except Korea. The BBC's correspondent in the South Korean capital says there is a disconnect between the hyped-up atmosphere and the reality on the ground.

I get emails from people in Europe asking me whether nuclear war is about to start - and then I look out of the window, in Seoul, and see a market where people amble gently between the stalls, sampling street food.

Around the world, headlines scream "danger" - but at what would be the epicentre of any war, there's not the slightest sign of fear.

While tension mounts far away, street dancers in Seoul accost passers-by with pamphlets advertising a concert.

Who's right? The headline writers or the putative war victims? Has the world suddenly got much more dangerous?

In one way, it obviously has.

North Korea is closer to possessing effective nuclear warheads and missiles, simply because it's had longer to sort out the problems.

North Korea tests missiles every one or two weeks to learn from their mistakes.

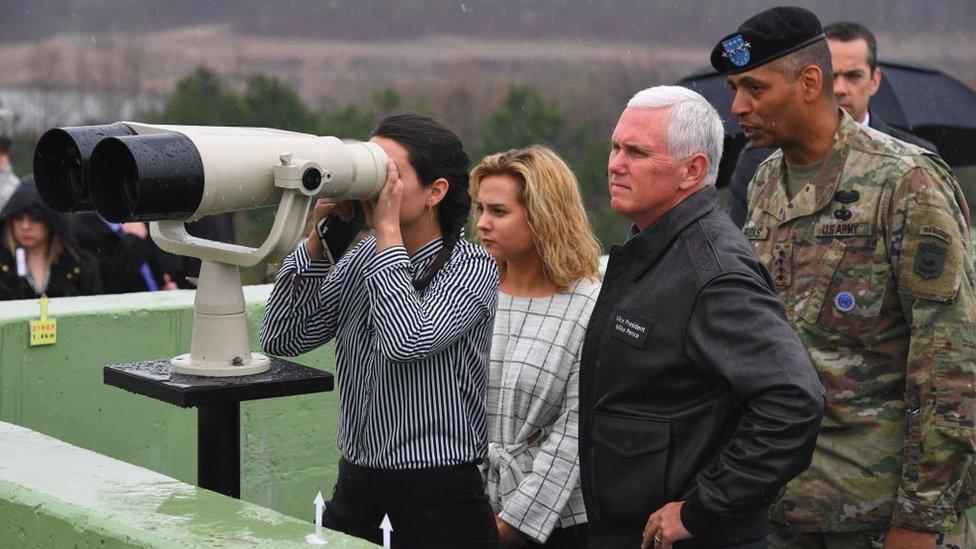

Speaking at the DMZ, US Vice-President Mike Pence said the "era of strategic patience is over"

But the expert view is that North Korea does not have the capability to strike the United States.

It is making progress, but it isn't there yet. A day after the fearsome display of missiles in Pyongyang, North Korea launched a dud - another one.

The other new element is President Trump himself. He's been sending different messages, which require a little analysis.

Under President Obama, the policy was called "strategic patience" - squeeze North Korea with sanctions, persuade others to do the same, particularly China, and sit it out.

At the demilitarized zone (DMZ) this week, Vice-President Mike Pence said the "era of strategic patience is over".

But is it? Or does it continue under another name?

The military option - an attack on North Korean nuclear installations - was considered by previous presidents and ruled out because half the population of South Korea lives in the greater Seoul area, which is within easy range of North Korean artillery. That remains true.

Decapitation - the assassination of Kim Jong-un - has also not happened for a variety of reasons: success couldn't be guaranteed, and it isn't clear what orders the military might have to retaliate against South Korea if the north's "supreme leader" were attacked. That hasn't changed.

Kim Jong-Un has defied international pressure to abandon his nuclear weapons programme

Whether the policy really has changed depends on whether President Trump has a different attitude to risk and the potential cost of war, perhaps a war that would suck in China.

In 1994, President Clinton considered attacking North Korean nuclear sites.

The United States had information the regime was about to move fuel rods from its reactor at Yongbyon, to the north of Pyongyang, to a reprocessing centre (the first step in making a nuclear bomb).

Plans were made to send fighters and cruise missiles to attack, but the order was never given.

President Clinton's Defence Secretary William Perry feared retaliation against South Korea.

But it was a plan that scared the North Koreans and enabled a deal to be done.

The US provided fuel to a fuel-starved economy, and North Korea agreed to freeze its programme (though it then cheated and the deal fell apart in 2002).

Today, Mr Perry believes the opportunity for what he calls "creative diplomacy" is there, particularly because China may be more helpful than it was during the Clinton presidency.

North Korea has to believe that the United States might attack and that, on this reasoning, makes President Trump's unpredictability an asset.

The recent parade in Pyongyang featured what appeared to be a new class of land-based ballistic missile

In recent days, the administration has downplayed the idea of attacking North Korea.

National security adviser Lt Gen HR McMaster said on Sunday: "All our options are on the table."

But, crucially, he added: "It's time for us to undertake all actions we can, short of a military option, to try to resolve this peacefully."

There is a pessimistic view and an optimistic view.

The bleak view is that President Trump is way out of his depth and acts impulsively.

On this reading, we are in great danger.

Sir Max Hastings, the author of an acclaimed history of the Korean War, has written: "As ever with this president, it is impossible to judge whether he means what he says, or even understands the significance of his words."

He cited a scenario that in his view echoed the way the world stumbled into war in 1914, through the "dysfunctional personality" of a leader.

The nightmare scenario now would be: "The United States delivers an ultimatum to North Korea, insisting it renounces its nuclear weapons.

"The half-crazed regime in the capital, Pyongyang, refuses.

"US aircraft and missiles strike at Kim Jong-Un's nuclear facilities.

"North Korea's neighbour and ally, China, responds by hitting carriers of the US Seventh Fleet in the Pacific.

"Suddenly, a major war erupts."

Might Mr Trump negotiate with North Korea?

But there is a more peaceful scenario, suggested by some experts in South Korea.

Prof John Delury, of Yonsei University, in Seoul, says: "The smart play for Mr Trump would be to return to those five wise words he said about Mr Kim on the campaign trail, 'I would speak to him.'

"The United States should swiftly negotiate a bilateral deal that freezes Mr Kim's nuclear and missile programme."

Under this scenario, money - a lot of money - would be given to North Korea in order to improve its economy.

There would probably have to be a guarantee that the regime wouldn't be toppled.

In this case, Kim Jong-un would have to be ready to negotiate (a huge if) and some trust would have to be put in him not to cheat and not to keep demanding more (another big if).

Which way will Trump jump?

- Published19 July 2023