Bali on alert as feared and revered volcano rumbles

- Published

Officials have raised warnings to the highest level, fearing an imminent major eruption

Mount Agung on the Indonesian island of Bali is showing increasing signs of moving towards a full-scale eruption. The volcano holds a special place in the life of the Balinese, as Rebecca Henschke reports.

Sudana walks through the thick volcanic mud that now covers his rice paddies on the bank of a river that runs from Mount Agung.

Cold lava, or lahar, has been rushing off the mountain here in Selat for the past two days bringing with it volcanic rocks and fertile soil.

"It's a natural cycle, these are the new rocks, gifts from the volcano that we will be able to build with in the future. And over time my land will be more fertile than before," he says looking up at the summit that is now spewing thick ash and gas thousands of metres into the air.

"We have much to be thankful for living in the shadow of a volcano."

Farmer Sudana sees the eruption as part of a natural cycle

Sudana remembers the last time his family's rice paddies were flooded with volcanic mud - it was in 1963, when the mountain last erupted. He was a child at the time and recalls people rushing down from the summit with serious burns from the hot ash and lava.

"We didn't have cars then, so the badly wounded were being carried and those who could walk were walking. We didn't have the same technology to monitor it then so people didn't leave."

This time the volcano has been rumbling for months and volcanologists in posts around the summit and across the world have been analysing its every move.

Made Katrini left her home high on the mountain more than two months ago when it first showed signs of erupting. Since then she has been living in a temporary government-run shelter. Her family of four is living in a small room made of bamboo and plastic sheets alongside four other families. When I ask how she is coping she breaks down and cries.

Made Katrini worries what the future will hold

"It's very hard not working, I am feeding my young children from the one cup of rice we are given a day, and instant noodles."

She has heard that her house is now covered with volcanic ash.

"I am so worried about what the future holds, what will it look like when we can return, what will be left for us. I can't think straight."

Reluctant to leave

Many others are refusing to leave. They are concerned about being left in limbo in the shelters without work to support themselves and their families.

Authorities have ordered everyone to leave a 12km (7.5 miles) radius exclusion zone but in many places life is continuing as normal.

Signs telling people to keep their distance from Mount Agung

We drove past a funeral procession and then past a sign saying "danger keep out, you are now entering into the red zone". Just a few minutes later we came across a primary school.

Parents were waiting on the road to pick up their children. A normal scene except for the masks they were all wearing.

Ningsih laughs nervously when I ask her why she hasn't left.

"We are watching closely she says, but we don't think it's time yet to leave. We will run once we know it's about to really erupt."

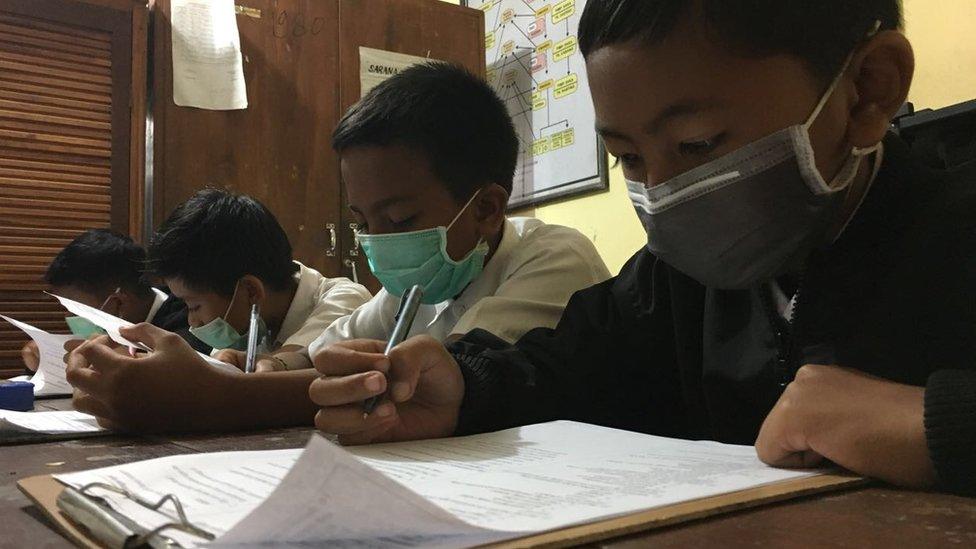

They are wearing simple surgical masks. Inside the school the students are going through the safety drill in case there is an eruption. The teacher shows them how to wear the masks properly but I wonder how much these simple masks will protect them.

"The masks will stop them from having breathing problems from the volcanic ash and prevent other health problems related to the volcanic eruptions," headmaster Ketut Gampil tells me.

"They will be safe as long as we keep watching and know when to run," he says with a smile.

Empty tourist sites

Mount Agung is the most sacred site in Bali. It is believed to be the abode of the gods and it's also the highest point on the island.

The power and energy it is showing now is awe-inspiring.

The Balinese have been praying for it to remain calm. And there is a surprisingly widespread sense of calm among the people living on its slopes.

Lessons go on, but schoolchildren wear face masks for protection from ash and fumes

But there is concern, too, about the impact the eruption is having on the tourism industry that the island so depends on.

The airport has been closed for two days, stopping hundreds of flights from getting in.

"We are very well prepared for the eruption," Balinese governor Made Pastika says.

"What we need to worry about is the long-term impact on the tourism industry and the rebuilding of the lives of the evacuees once this is over."

Hotels and restaurants in the normally busy diving hub of Padang Bai are ghostly quiet.

There are no guests, a waitress selling ice-cream at a cafe tells me.

As the sun sets all the staff sit together looking up at the volcano from the beach front. At night there is a red glow from the crater. It's a dramatic sign.

- Published27 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published27 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published26 November 2017

- Published30 September 2017

- Published27 September 2017

- Published26 September 2017

- Published25 September 2017