Up close and personal with the biggest drone squadron ever

- Published

Before taking office, Donald Trump called the war in Afghanistan a "total disaster". But last August he changed his mind and announced that the US would stay until the war was - in his words - "won". Military commanders see air power as key to the hoped-for victory, and have assembled in the country what they say is the biggest drone squadron ever.

I'm lying in the belly of a KC-135 "stratotanker", peering down at the snowy IS-infested mountains of north-eastern Afghanistan.

Suddenly the first wasp-like F16 fighter jet comes into view. It delicately positions itself under the boom that hangs down from the back of this flying fuel tank and - moments later - has locked on. The "Viper" is now taking on hundreds of pounds of aviation fuel a second.

We are so close I can see the pilot glance up at me, yet - unbelievably - this intricate ballet is playing out at high speed and thousands of feet up.

A couple of minutes later, its tanks full, the fighter arcs away and another noses up to take its place.

The scene is so dramatic, beautiful and bizarrely serene it is easy to forget its real purpose - wreaking havoc and death among the insurgent fighters that have been making steady inroads in Afghanistan since the Nato combat mission here ended in December 2014.

KC-135 "Stratotanker"

US Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker

It is the backbone of the air war in Afghanistan, yet has been part of the American fleet for an incredible 60 years

Stratotankers are key to the air war because fighter jets typically can't fly long missions - the KC-135 allows them to attack targets and provide air cover to ground troops for much longer

The plan is to keep the KC-135 fleet in service for another 40 years - raising the astonishing possibility that fighter aircraft in battles in the middle of this century could be being serviced by a plane that is almost 100 years old

The sense of being insulated from the conflict is hard to shake.

Back on the tarmac at Kandahar airbase, I watch an MQ-9 wobble uncertainly out on to the runway.

The "Reaper" drone is surprisingly flimsy-looking, but this strange creature with its domed fuselage, distinctive downward slanted tailfins and rear-mounted propeller is probably the most controversial aircraft in America's entire fleet.

The MQ-9 represents asymmetrical warfare at its most stark.

Critics say these "unmanned aerial vehicles", as the US Air Force prefers to call them, alter the moral calculus of war by taking the pilots out of the planes, thereby converting deadly conflict into something more like a video game.

Maj Gen James B Hecker has the buzz cut, square jaw and easy manner you'd expect of a senior US Air Force officer. I'm worried he might be uncomfortable talking about the ethics of the drone war. But, as we sit in the shade of some sand-coloured camouflage netting alongside the runway, it becomes clear he's actually keen to talk about this notorious aircraft.

As he talks, I realise why.

He explains he's spent thousands of hours in the air-conditioned comfort of an airbase base back home in the US watching the footage from the array of high-tech cameras and sensors that are packed into the MQ-9.

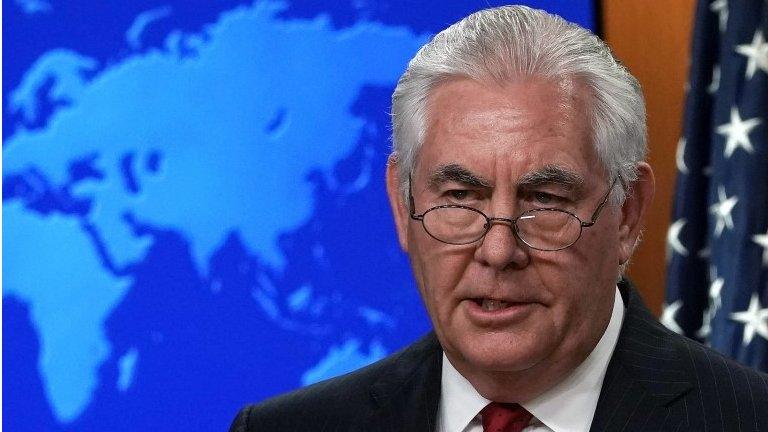

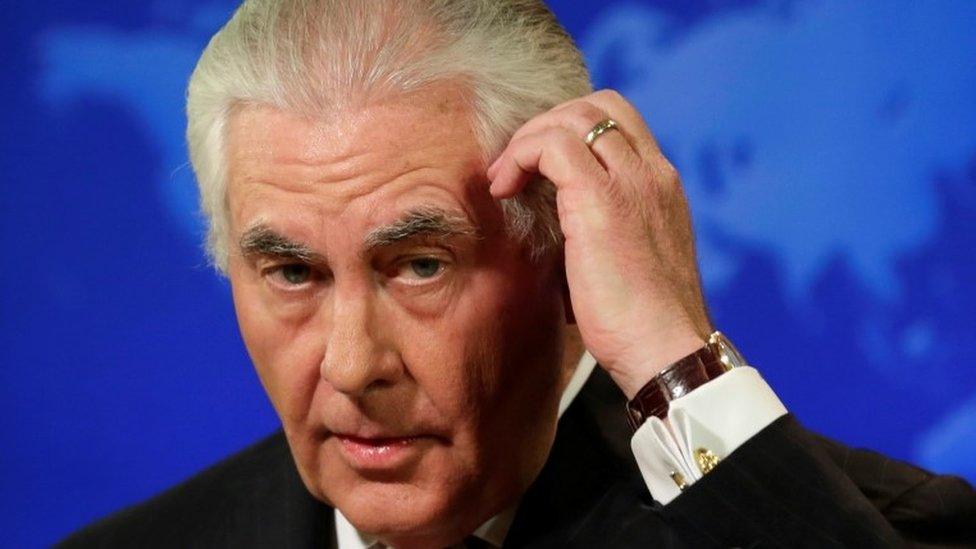

Maj Gen James B Hecker

"I've spent weeks looking at a single compound in Afghanistan," he tells me.

"You kinda get to understand the patterns of life. You get a sense of belonging. You're kinda in touch with them when you watch them for so long.

"You watch dad playing soccer with his son, you watch him flying his kite with his daughter and kiss his wife goodnight. And you watch him sleep outside in the summer when it is hot."

He pauses, giving me a moment to consider this chillingly intimate image.

I imagine the invisible aircraft, thousands of feet above the scene, its blank eyes staring down at the banal routines of family life.

"Then dad would go out and plant an IED" - a home-made explosive device - "that might kill one of our soldiers, and then we would have to take him out."

He says this without any apparent emotion, and pauses again.

"We have to do that. We know that son, that daughter, will never have a dad again, OK? And that wife will never have a husband. Now that's the last thing we want. But what we won't stand for is for the Taliban to go in and kill a bunch of innocents. And that's what they are doing right now - blowing up innocent people."

This idea of unblinking surveillance backed up by deadly force is, of course, the most potent of propaganda.

The message back home is that these drones are precise, even surgical tools, dispensing death only when the target has been identified with certainty.

The message to the insurgents is very different - "We are always watching, you are never safe."

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

The vast drone squadron America has amassed here - along with all the other aircraft - is evidence of the massive increase in the intensity of the air war that is a key part of President Trump's new strategy in Afghanistan.

Another key part is building the offensive capability of Afghan forces.

According to the commander of US forces here, Gen John Nicholson, the message to the Taliban is simple: "Reconcile or die."

Gen John Nicholson

What he means is, "We will continue the fight until you are willing to negotiate some kind of peace."

But it is a message the Taliban have heard before.

The truth is, the war here in Afghanistan has always been giddyingly unbalanced.

Killing has always been easy for the coalition forces.

Seventeen years into this conflict, the real challenge remains trying to create real momentum towards peace and stability.

And the commanders here really do believe that is happening now.

Other observers insist peace remains as elusive as ever, despite the technical wizardry bearing down on this fractured country.

Read more

The Memphis Belle with full payload on show at Barksdale. The plane took part in the first Iraq War

The most feared bomber plane of the 20th Century is still going strong after 60 years in service in the US military - from Vietnam to Afghanistan. And she will keep on flying until 2044. How does this 1950s behemoth survive in the era of drones and stealth aircraft?

- Published14 March 2018

- Published23 August 2017

- Published31 January 2018

- Published18 September 2017

- Published8 June 2017

- Published25 April 2017

- Published12 August 2022