Outlaw or ignore? How Asia is fighting 'fake news'

- Published

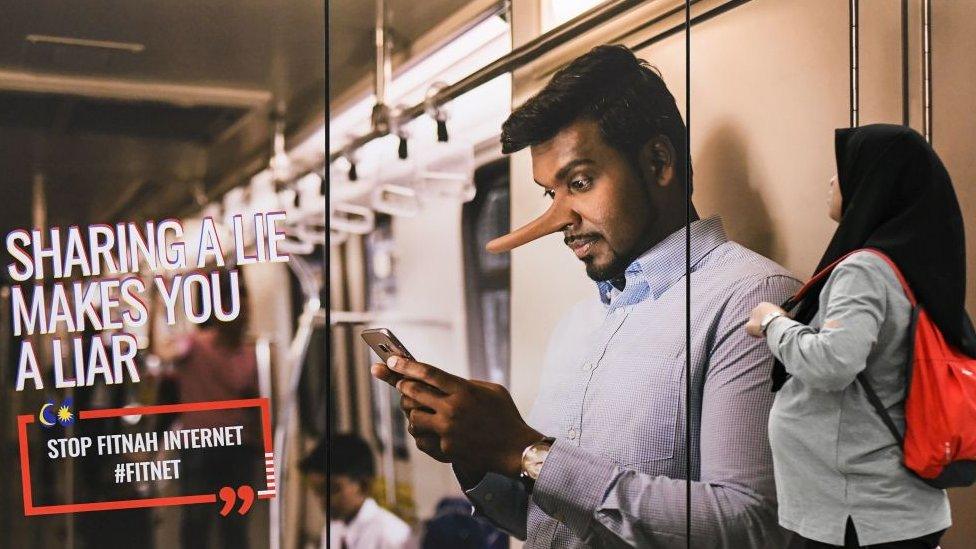

The Malaysian government has put up posters in Kuala Lumpur warning citizens against sharing fake news

Everybody is talking about it: fake news.

President Trump decries it every time he sees a critical article, the Pope has condemned it, governments are fretting about its influence, holding parliamentary hearings.

And now Malaysia has passed a law criminalising it, with a penalty of up to six years in jail. Yet no-one has defined what it is.

The term first came to prominence during the 2016 US presidential election campaign. But the problem of deliberately falsified news articles, masquerading as properly-researched journalism, goes back centuries.

However, the Malaysian government's definition in the recently-passed law is far more sweeping than that.

It has criminalised the dissemination of "any news, information, data and reports, which is or are wholly or partly false, whether in the form of features, visuals or audio recordings or in any other form capable of suggesting words or ideas".

Human rights groups have been quick to point out that this could be used against anyone who makes an error in their reporting or social media posts.

Moreover at least one member of the government has already stated that, when it comes to articles critical of Prime Minister Najib Razak, especially over the notorious 1MDB scandal, where billions of dollars of a government-run investment board are alleged to have been misappropriated, any information not verified as true by the government will be viewed as fake news.

Mr Najib has been at the centre of a controversy over Malaysia's state development fund

The fact that this law has been rushed through right before what is likely to be a hard-fought general election has raised suspicions that its real purpose is to intimidate government critics.

It is not clear anyway that Malaysia has a serious fake news problem.

In a response to the concerns expressed about the new law, the communications and multimedia minister Salleh Said Keruak highlighted the foreign media's failure to get the sometimes complicated string of official titles for high-ranking Malaysians right - irritating, yes, but hardly a threat to national security.

The article goes on to excoriate mainstream media which have published negative pieces about Mr Najib, calling them fake news, and thus rather confirming suspicions that the law is aimed at them, rather than the manipulation of social media opinion through fraudulent Facebook accounts and automated Twitter bots.

'Better safe than sorry'

Singapore is the other country which has raised the alarm over fake news, holding 50 hours of parliamentary hearings.

Facebook's policy director Simon Milner was publicly dressed down by the law and home affairs minister K Shanmugam over his failure to acknowledge the full extent of data taken by the data analysis company Cambridge Analytica when he testified to the British parliament earlier this year.

Academics speaking at the Singapore hearings presented an alarming scenario of disinformation campaigns launched by foreign actors bent on attacking the island state, of cyber armies in neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore working as proxies for other countries in undermining national security.

It also gave Singapore academics and officials an opportunity to snipe at the US belief in free expression, the "marketplace of ideas", which had allowed the abuse of personal data on Facebook to take place, in contrast to Singapore's "better safe than sorry" belief in a more tightly regulated society.

But the actual examples of fake news which have come up during this national debate have mostly been prosaic; a hoax photo showing a collapsed roof at a housing complex, which sent officials rushing unnecessarily to the scene; and an erroneous report of a collision between two trains on the light rail transit line.

Irritating and worrying for some, for a while, but hardly likely to bring Singapore society to its knees. In any case both Singapore and Malaysia already have plenty of laws capable of penalising false, inflammatory or defamatory comment.

A poisonous tide

In the country where social media misinformation has had the most devastating impact, by contrast, there is no clamour for a fake news law.

Myanmar too has a raft of existing harsh laws sweeping enough to stifle any reporting deemed a threat to the state or society, laws which all too often have been used to jail journalists.

But these laws have been unable to prevent a poisonous tide of hate speech on social media, which has helped ignite anti-Muslim sentiment.

Myanmar famously leapt from being a society largely without even old-fashioned telephone lines, to one with more than 40 million mobile phone accounts, in just three years.

Seventeen million people have Facebook accounts, and as in so much of Asia, this is how most Burmese send messages and get their news.

Most don't bother with email accounts. This has coincided with the end of strict military censorship, and the emergence in the mainly Buddhist population of a primeval fear of the small Muslim minority.

Fake news spread on Facebook is not helping the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar

It has been all too easy to find cartoons and doctored photographs on Facebook which depict Muslims in a sinister and derogatory way. Worse still, large numbers of posts about Muslims are completely false, with photographs purporting to show atrocities against Buddhists by Muslims which are from a completely different part of the world.

The government has done nothing to stem this tide of disinformation, at times appearing to encourage it.

For example the Facebook page of the Myanmar armed forces still has on it a gruesome photograph with a caption stating that the dismembered bodies of infants, being dragged by apparently Muslim men, are Rakhine Buddhists killed by Rohingya militants in 1942.

In fact the photograph is from the Bangladesh independence war in 1971.

When journalists, myself among them, were given photographs in September 2017 during a government-run tour of Rakhine state, supposedly showing Muslims burning down their own homes, backing the assertion by officials that this was the cause of the destruction of Rohingya villages, we were quickly able to ascertain that the perpetrators in the photos were actually displaced Hindus dressed up as Muslims.

Who is burning down Rohingya villages?

Yet the government spokesman posted one of the photos on his Twitter feed proclaiming "It's Truth", although he later removed it. I was told in all seriousness in one Rakhine village that Muslims used to cut up Buddhists and cook them with their beef stew.

These kinds of stories are circulating unchallenged in Myanmar, creating a tide of fear and hate which then intimidates anyone trying to advocate a more tolerant approach into silence.

The UN Special Rapporteur to Myanmar Yanghee Lee, who has herself been subjected to vicious online abuse for her focus on human rights in Rakhine, and has now been banned from entering the country, has described Facebook there as "a beast".

Facebook says it takes the problem of hate speech very seriously, but has yet to stop the site being used to stir up sectarian conflict.

The social media game changer

The other country where social media has had a profound impact is the Philippines, where critics of President Duterte have accused his supporters of "weaponising" Facebook and Twitter to twist public opinion and silence dissent.

Filipinos are among the heaviest users of Facebook in Asia, with more than one third of the population visiting the social media site regularly.

The use of Facebook has become extensive in the Philippines

This is has made it a potentially game-changing arena for political actors who know how best to use it, in a country which has long had a lively and competitive traditional media.

Long before the 2016 election which propelled Rodrigo Duterte, a late candidate with outsider status, to the presidency, the internet was already being exploited by public relations experts promoting products and opinions with so-called "click factories", where thousands of low-paid workers raised the clicks for specific websites, and companies openly offering hundreds of fake Facebook or Twitter accounts in support of the online profile of clients.

After announcing his candidacy in November 2015 Rodrigo Duterte hired social media experts to craft a strategy which outflanked the usual dependence on endorsement from mainstream newspapers and television channels.

It worked brilliantly, tapping into a hitherto unarticulated yearning for change among many Filipinos.

But researchers have also detected what they believe is the use of automated bots and fake Facebook accounts to amplify the pro-Duterte message, something the president's team has denied.

Mr Duterte successfully leveraged Facebook to help his election campaign

The online news site Rappler published a detailed report about this in October 2016, enraging Mr Duterte's supporters, and, it believes, prompting the ruling in January this year by the Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission that the site is illegally owned by foreign investors, a claim first made by the president last year.

Rappler also highlighted the way Facebook's algorithms could be "gamed" to ensure certain content dominates users' newsfeeds.

Leaving aside the allegations of social media manipulation, what President Duterte's supporters have succeeded in doing is using Facebook and other sites to wage a war of words against his critics, or anyone publishing unfavourable reports.

I experienced this in September 2016 after the BBC published a report on Mr Duterte's campaign against drugs dealers and users which has resulted in thousands of police and extrajudicial killings.

I received a flood of hostile messages, and a few death threats on my Facebook page, and the BBC complaints site was swamped with almost identical protests over "erroneous and biased" reporting. Maria Ressa, the CEO and founder of Rappler, was at one point getting 90 hate messages an hour.

In part this militant response has been shaped by Mr Duterte's own depiction of his presidency, more as an existential struggle to save his country than just another administration.

Mr Duterte uses emotive and bellicose language to describe his mission, openly threatening to kill those who stand in his way, including journalists, and suggesting he may in turn be killed, by unnamed enemies.

Having successfully motivated those who voted for him into believing he could be a one-man saviour for the many ailments afflicting the Philippines, he, like President Trump in the US, has also instilled in his supporters a deep mistrust of traditional mainstream news sources, as controlled by powerful vested interests set on ensuring the failure of his presidency - "presstitutes", in their preferred term.

Nowhere has the political climate been more polarised than in Myanmar and the Philippines.

Yet hearings at the Philippines Senate concluded that a specific fake news law was unnecessary, and possibly counterproductive.

Clarissa David, a professor of mass communications at the University of the Philippines, testified to the Senate about the dangers of an information environment she described as "polluted", with no one sure any more what is real and reliable, and what is fake.

But she warned against easy definitions of fake news. And trying to outlaw it, she argued, is not worth the inevitable cost there will be for media freedom.

Hers is an argument which was made, but lost, in Malaysia.

- Published26 March 2018

- Published3 April 2018

- Published22 January 2018

- Published31 December 2017