Sumo wrestling: The growing sexism problem in Japan's traditional sport

- Published

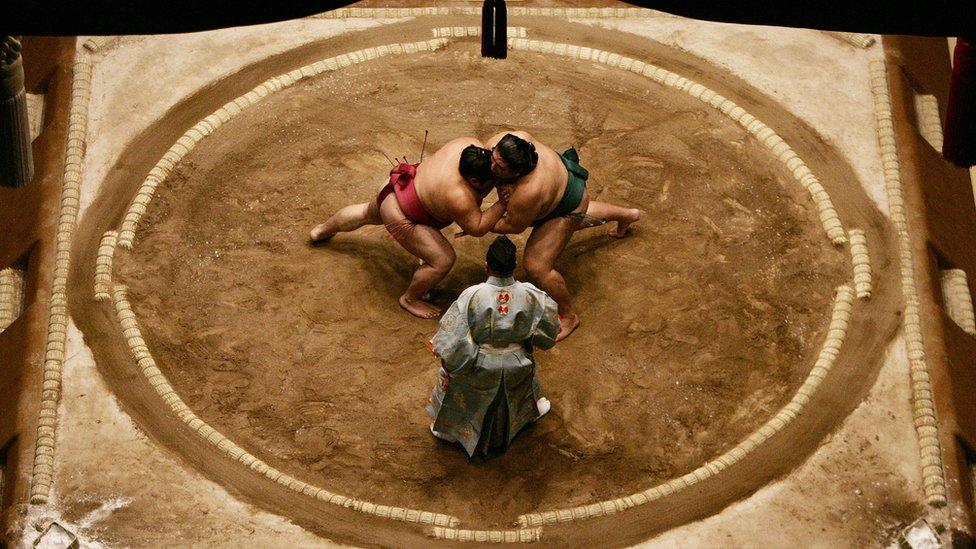

Sumo wrestling dates back thousands of years in Japan

Japan's sumo wrestling authority has postponed a decision on the sport's "men-only" policy.

The Japan Sumo Association (JSA) met after a recent string of scandals, including when women were made to leave the ring after stepping in to help a man.

Women are traditionally believed to be "unclean" and cannot enter the space.

JSA director Toshio Takano said they needed more time, calling it "an extremely difficult issue".

Why is sumo under fire?

In April, Maizuru city mayor Ryozo Tatami collapsed in a sumo ring, known as "dohyo", when he was giving a speech.

Women rushed to help the mayor, but they were ordered to leave by the referee.

Local media reports spectators then watched salt being thrown into the ring - a practice performed before a match to purify the space.

Salt is thrown into the ring to "purify" the space

The Japan Sumo Association faced universal condemnation for the referee's actions, and association chief Nobuyoshi Hakkaku apologised for the "inappropriate act".

But within days, the association came under fresh fire after denying the female mayor of a city entry to the ring.

Tomoko Nakagawa, mayor of Takarazuka, asked the association if she could deliver a speech before an exhibition match in the city, but was reportedly told to "give due respect to tradition".

"Female mayors are also humans," she reportedly said in a speech delivered beside the ring, external. "I am frustrated that I cannot give this speech on the dohyo just because I am a woman."

Mayor Tomoko Nakagawa is fighting against the men-only policy in the sport

The association also ruled girls could not take part in a spring sumo tour in which young people could join the wrestlers in the ring, citing safety concerns - despite girls having taken part in previous years.

Why are women denied entry to the ring?

Sumo dates back thousands of years, and to this day maintains many ancient traditions.

Mark Buckton, a former commentator and columnist with the Japan Times, says the practice has links to Japan's Shinto religion.

"It's never been considered a sport in Japan," Mr Buckton told the BBC. "It's far deeper in the Japanese psyche."

You may also be interested in:

Traditionally before a match, a hole is made in the centre of the dohyo and filled with nuts, squid, seaweed and sake by Shinto priests.

The hole is closed, enshrining inside a spirit. Sumo wrestlers then perform a ritual stamp and clap to scare away bad spirits.

"The ring is considered a holy Shinto space," explained Mr Buckton.

Sumo wrestlers perform the ritual to clear evil spirits from the dohyo

Traditionally in the religion, women were considered impure because of their menstrual blood, and denied entry to the space because of this.

Mr Buckton explains any blood is believed to sully the space - if male wrestlers bleed on the dohyo, it is purified with salt.

While women can and do compete in amateur sumo wrestling around the world, they cannot enter the ring at Tokyo's 11,000 Ryogoku Kokugikan arena, or compete in professional tournaments.

Is the policy likely to change?

Sumo chief Oguruma, who only goes by one name, told local media after Saturday's JSA meeting that the policy has been in place "for hundreds of years".

"We can't change it in an hour," he said.

Certainly, the JSA has not bowed to pressure before now.

In 2000, the then governor of Osaka, Fusae Ota, asked the sumo association to allow her to enter the ring so she could present a trophy to the champion wrestler, but her request was rejected.

Women compete in sumo tournaments around the world

Mr Buckton thinks the association will never change the policy, due to the long-standing traditions in the sport and what he considers a limited awareness of feminism in the country.

"The sumo association are just waiting for a few more scandals to pop up, and for this to fade away," he said.

"It's not a major controversy in Japan at all."

But as the #MeToo movement takes hold in Japan and recent controversies sparked by Japanese female politicians discussing the difficulties of being a woman in work, this latest debate about women in sumo may not fade as quickly and easily as previously.

- Published5 April 2018

- Published20 August 2015

- Published31 July 2017

- Published25 April 2018

- Published10 March 2015