Pakistan activists targeted in Facebook attacks

- Published

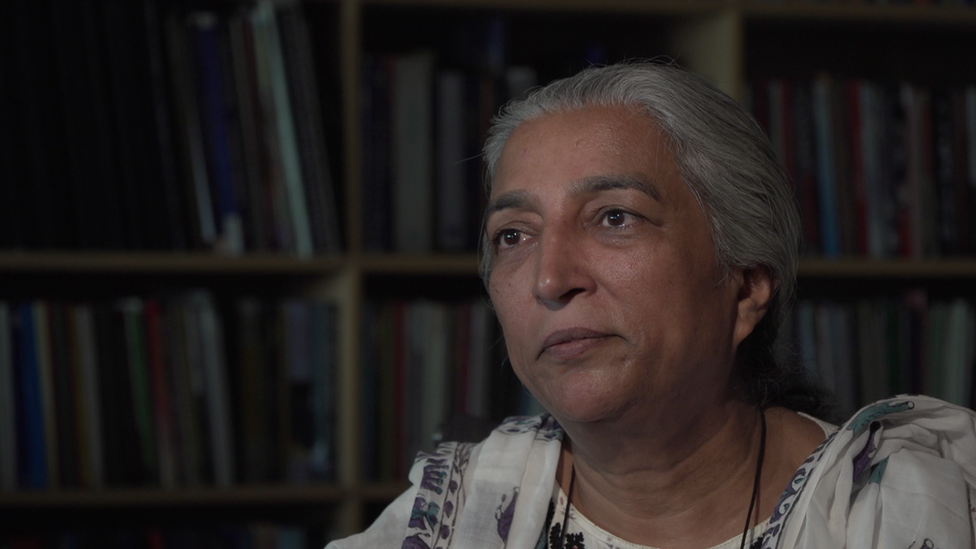

Diep Saeeda has been a human rights activist for 25 years

In December 2016 Diep Saeeda, an outspoken human rights activist from the Pakistani city of Lahore, received a short message on Facebook from someone she didn't know but with whom she had a number of friends in common: "Hy dear."

She didn't think much of it and never got round to replying.

But the messages weren't coming from a fan of Mrs Saeeda's activism - instead they were the start of a sustained campaign of digital attacks attempting to install malware on her computer and mobile phone to spy on her and steal her data.

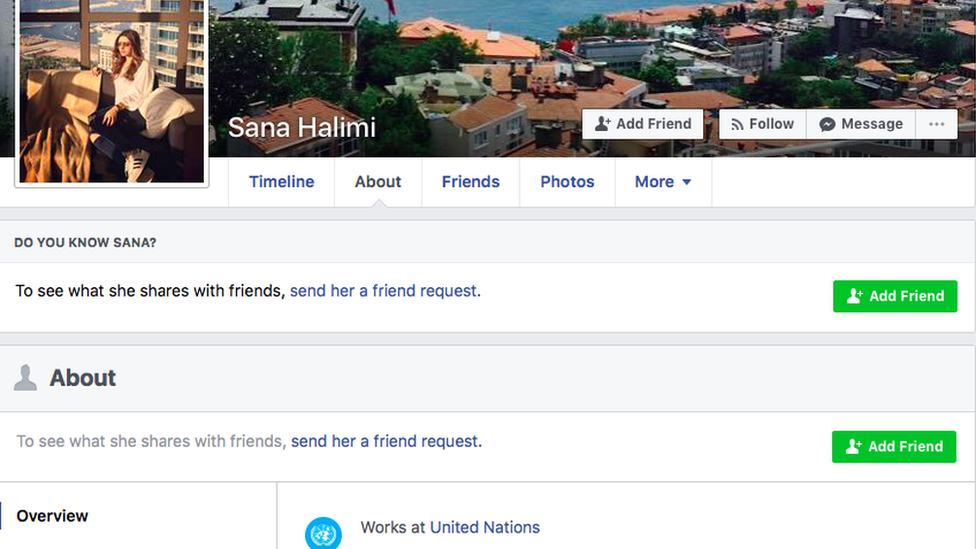

Over the next year, she received multiple messages from the same Facebook account, apparently run by a young woman calling herself Sana Halimi, claiming to work for the United Nations.

However, the attackers targeting Mrs Saeeda made crucial mistakes that allowed researchers from human rights group Amnesty International to trace a number of individuals, external linked either to the operation or to the malware used.

They include a British-Pakistani cyber security expert running a company he claims to be based in Wales, and another who used to work for the Pakistani army's public relations wing.

Mrs Saeeda is clear whom she believes is ultimately responsible for the attacks: "I'm convinced these are intelligence agencies... They try to harass people and force them to leave the country."

Mrs Saeeda was contacted by "Sana Halimi" a year before the account began sending her malware

She says in the past they targeted her for promoting dialogue between ordinary Pakistanis and Indians.

"There was a time they would visit my home or office on a daily basis. When I get up in the morning, there would be two people outside my home."

But she says the malware attacks were more invasive than anything she had previously experienced.

Crackdown fears

Amnesty International has spoken to three other Pakistan human rights activists who have been targeted in the same way.

They discovered that the main piece of malware being used had also been used in previously documented attacks on Indian military and diplomatic officials.

Amnesty International say they have no evidence of Pakistani state involvement and are unable to say who is ultimately responsible for conducting the attacks.

Sherif Elsayed-Ali, director of global issues at Amnesty, told the BBC they were calling on the Pakistani authorities to investigate the attacks "as a matter of urgency… and to ensure that human rights defenders are adequately protected both online and offline".

Human rights groups have repeatedly warned that the Pakistani intelligence services appear to be cracking down on activists who criticize them.

In January 2017, a group of bloggers went missing for a number of weeks before being released. Two subsequently told the BBC that they had been detained by the security services and tortured.

An activist vanishes

A year after first establishing contact with Mrs Saeeda, "Sana Halimi" sent her the first messages with malware attached.

Mrs Saeeda was at the time in a state of panic. One of her closest friends, fellow activist Raza Khan, had disappeared.

The 40-year-old, who worked on promoting better relations between Pakistan and India, had been attending a talk on extremism on 2 December 2017.

He hasn't been seen since leaving the event. The next day, friends found his door locked and light on - his computer missing.

They believe he was taken into custody by the intelligence services.

A few days after Mr Khan's disappearance, as Mrs Saeeda was becoming increasingly vocal in the media, she received her first malware attack.

"Sana Halimi" sent her a fake Facebook login page via Facebook Messenger. Had she clicked on it, the site would've recorded her Facebook password.

She didn't though and a few weeks later received another malware attack, again from "Sana Halimi." This time the message contained a link - apparently to a set of New's Year's Eve-themed photo filters.

In fact, it was malware designed to hack into her mobile phone and intercept text messages.

Again, Mrs Saeeda didn't click on the link. The attackers changed tactics.

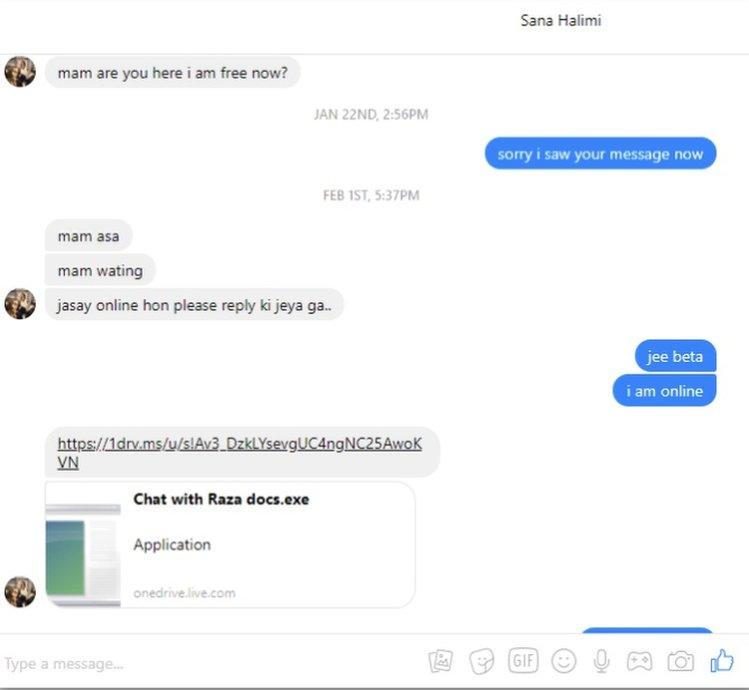

"Sana Halimi" messaged Mrs Saeeda, telling her she needed to talk to her privately about the disappearance of her friend Mr Khan.

Mrs Saeeda, desperate for anything that could help locate Mr Khan, became suddenly interested.

The messages continued for over two weeks and culminated in a message from "Sana Halimi" purportedly containing an attached document that would help her "understand" what had happened to Mr Khan.

Mrs Saeeda attempted to download it but it was blocked by her computer's antivirus software. The document appeared to be another piece of malware.

Over the subsequent weeks and months, Mrs Saeeda was repeatedly targeted in further attacks, this time over email.

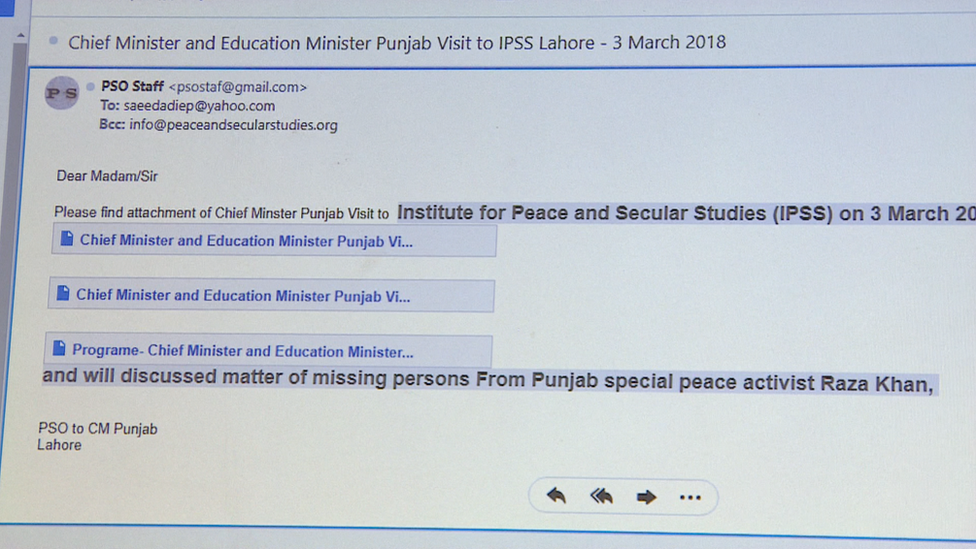

One email she received claimed to be from the office of the chief minister of Punjab, the province she lived in.

It said the chief minister would be visiting her office to discuss the case of her still missing friend Mr Khan.

By this time though, Mrs Saeeda was aware she was being targeted and forwarded the emails to Amnesty International instead of downloading the files.

They discovered Mrs Saeeda had been sent at least two different pieces of malware, one by Facebook, and one by email.

The malware attached to the email could, amongst other things, "log passwords, take pictures from the webcam, activate and record audio from the microphone, steal files from the hard disk".

They identified this malware as a software called Crimson.

Crimson attacks have been documented before. A number of cyber security firms wrote about the malware in March 2016 after discovering it was being used to target Indian military and diplomatic figures.

Claudio Guarnieri, from Amnesty, told the BBC the Crimson malware used to target Mrs Saeeda was "almost identical" to that used in the past.

An independent cyber security firm told the BBC it was "highly confident" the attacks documented by Amnesty had been carried out by the same group behind the attacks on Indian targets.

'Digital spy services'

Amnesty was able to use the malware they examined to identify some of those associated with creating it.

They discovered the malware linked to the New Year's Eve photo filters that "Sana Halimi" had sent to Mrs Saeeda via Facebook would send any stolen data to a server registered in Lahore.

The owner of the server was a man called Faisal Hanif whose email address and phone number were listed in the server details.

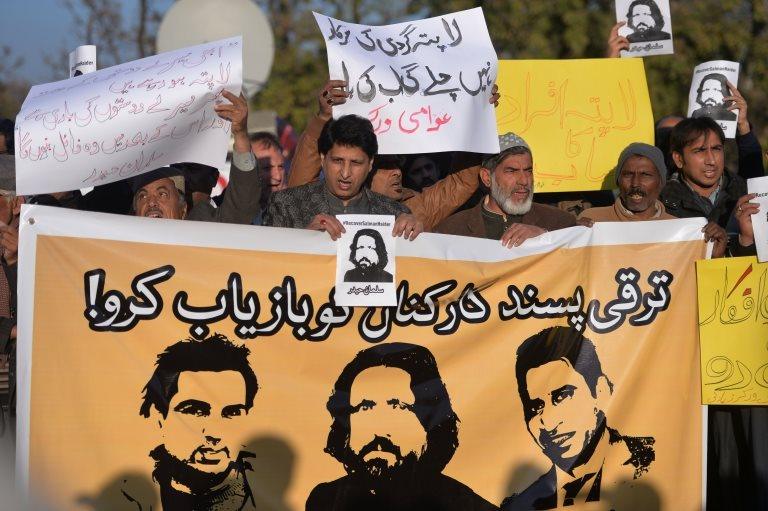

The disappearance of the bloggers last year prompted a number of protests

These linked to a Facebook profile revealing that Mr Hanif owned a company called Super Innovative.

On its website, Super Innovative advertises digital spy services, which allow you to monitor calls, text messages and emails of your "children, company employees or loved ones" whilst remaining "unnoticeable".

The company website claims to be based in Penarth, Wales.

When the BBC visited the property, a woman living at the address admitted knowing Mr Hanif and told the BBC he did occasionally visit from Pakistan. But she said she knew nothing about the company Super Innovative.

Mr Guarnieri says there is no evidence Mr Hanif or Super Innovative were involved in sending the malware to Mrs Saeeda but his research connects Mr Hanif to the creation of the malware used to target her.

"What we believe is that they were the ones tasked to create these tools, but not necessarily the ones that used it."

When contacted by the BBC, Mr Hanif denied involvement in the attacks on Mrs Saeeda.

He said he believed he had been hacked - and his details falsely used to register the server linked to the malware. He denied having created any spyware that could be used to steal mobile phone data.

Shortly after the BBC contacted Mr Hanif, the server linked to the attacks was taken down.

No more email attachments

In researching the creators of a previous version of the Crimson malware, the Amnesty team came across a massive lapse in security by those linked to it.

A folder containing as yet unreleased copies of the malware was left publicly accessible.

Mr Guarnieri told the BBC it was a "pretty common mistake" for those working in the field to make.

As well as copies of the malware they found a word document that appeared to be an outline of an online team dedicated to targeting perceived opponents of the Pakistani army.

The document states that part of their role consists of checking different websites "to see if there are any anti-army content on it, so we try to take them down or at least trace the administrators… We are working on different target accounts to trace their IP addresses or to compromise their accounts."

By establishing the email address associated with the metadata of the document, Amnesty researchers traced it to an Islamabad-based cyber security expert, Zahid Abbasi.

When confronted by the BBC, Mr Abbasi confirmed he had previously worked for a year for the Pakistani military's public relations team (ISPR) and that the document was genuine.

He admitted his role included tracing the IP addresses of "people abusing institutions" online and "compromising their accounts" by, for example, sending them fake Facebook login pages.

However, he denied that human rights activists were amongst those targeted or that he had any connection to the Crimson malware.

There is no evidence that Mr Abbasi was involved in the attacks on Mrs Saeeda.

There was no immediate response to the BBC's request for comment from the Pakistani army.

Mrs Saeeda told the BBC: "After these attacks I feel insecure - even my own children sending me an email, I'm scared someone is using their name. I don't open emails with attachments."

She added tearfully, "The people who are doing it are spending their resources and their energy on a person who has given 25 years in [peace] activism."

- Published10 January 2018

- Published15 May 2017

- Published17 December 2017

- Published25 October 2017

- Published9 March 2017

- Published2 March 2018