Obituary: Major Geoffrey Langlands, Pakistan's English teacher

- Published

Geoffrey Langlands was born in Yorkshire, but lived most of his 101 years in Pakistan

It is not every teacher whose death sends an entire country into mourning. But then, Major Geoffrey Langlands was no ordinary teacher and his was no ordinary life.

The tale of how a British orphan came to be Pakistan's best-loved teacher, meeting princesses, teaching prime ministers and surviving kidnap while maintaining a healthy respect for a well-shined shoe, porridge oats and the morning newspaper, could be straight out of a story book.

He was, the New York Times said in 2012, "the quintessential Englishman of old, a living relic of the Raj".

But "the major", as he was affectionately known, was more than a vestige of a bygone age. By the time of his death at 101, his devotion to education had transformed the lives of thousands of children growing up in some of Pakistan's most remote and lawless regions.

An inauspicious beginning

World War One was still raging when Geoffrey Langlands and his twin brother John were born in Yorkshire in October 1917.

The twins' father died the next year, one of the millions killed in the 1918 flu pandemic. Their mother decided to move south, to Bristol, where her parents lived.

But Langlands' mother died when he was 12, leaving the children orphaned and reliant on the kindness of friends and relatives.

This kindness would see him enrolled at King's College, in Taunton, Somerset. From there, he would go on to take his first teaching job, at a school in Croydon in south London.

But none of this gave any hint of what was to come.

He arrived in 1947, as Pakistan gained its independence

Maj Langlands was in his early 20s when World War Two broke out. He volunteered to join the army and became a commando, taking part in the disastrous Dieppe Raid in 1942.

His posting to India in 1944 would shape the rest of his life. After the war, he stayed on to witness firsthand the end of the British Empire in India, and the deadly violence that engulfed the country during partition in 1947 - when two independent states, India and Pakistan, were created.

Maj Langlands was assigned to Pakistan's new army, and spent much of the period travelling around the country by train. In interviews later, he would tell of how he navigated the early, chaotic days that left more than half a million dead, even guarding a train full of Indian soldiers in the newly created capital, Lahore.

He laid the blame for what happened on the leadership at the time.

"It could've been done more peacefully and many wars that followed could've been avoided," he told a Stanford oral history project, external in 2015.

Maj Langlands stayed on in Pakistan after partition, but in the early 1950s a chance conversation would set him on the path that would come to define his life.

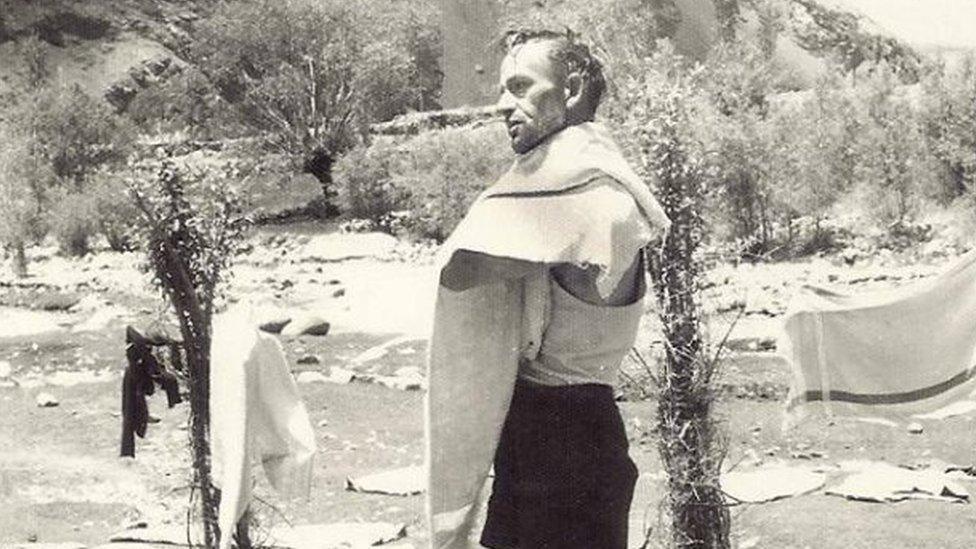

He became a teacher at a leading boys' school, taking students on treks through the mountains (pictured top right in the 1960s)

Businessman Haroon Rashid, a student of Aitchison College in Lahore in the 1960s, often heard the tale of how the then-military ruler Ayub Khan had asked the major what his future plans were.

"Langlands told him he was a teacher before the army and would like to go back to teaching. In a prompt response Ayub said there was a shortage of teachers in Pakistan, and would he like to stay back?

"Langlands - in an equally prompt reply - agreed."

In fact, Maj Langlands had already found the school he wanted to teach at: he described Aitchison College as the "Eton of Pakistan".

He would spend the next 25 years teaching there, impressing the children with his love of Pakistan's mountains, long hikes and devotion to teaching.

It was also here he would teach his best-known students. According to The Telegraph newspaper, one US ambassador would later joke he had taught half the cabinet, external. Half the cabinet, that is, alongside one president and two prime ministers - including incumbent Imran Khan.

Mr Khan credits Maj Langlands' influence with instilling "the love for trekking and our northern areas in me", describing the former teacher as "firm yet compassionate".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

By 1979, Maj Langlands was looking for a new challenge. He would find it in the mountainous area of North Waziristan, on the border with Afghanistan.

This tribal area was a world away from the Lahore he was used to. For the head teacher he went to work under, it proved too much.

"He stayed there for one year, and then he more or less walked out," Maj Langlands once told the BBC. "He said this was a dreadful place."

Maj Langlands, however, was not deterred - despite knowing the risks.

"The tribal areas were completely without law, and therefore they didn't welcome any visitor coming into their area. They would usually be kidnapped," he said.

More lives in profile:

Maj Langlands was no exception. He was pulled from the car he was travelling in in 1988. The reason? A local chief was upset he had not won an election, and hoped kidnapping the well-connected former soldier might make officials change their minds.

He didn't know that at the time however, and when the car initially stopped, Maj Langlands began to wonder what they were talking about.

"I thought maybe they are discussing how to kill me," he recalled. "But I do not worry about those things. Life comes as it comes."

He was released after six days when his captors realised the plan was not going to work - but not until a photograph of them all together had been taken.

Later that year, he moved further north to take charge of a new school in Chitral, which would later be named in his honour. He even met Princess Diana there as she toured the region.

Through the school, Maj Langlands changed the lives of thousands.

The school started with just 80 students. By the time he retired, aged 94, there were 800. He spoke proudly not only of how the boys were getting scholarships to the top universities, but also an increasing number of girls.

"He promoted the poor of Chitral," Farhat Tamas, a professor of psychology in Peshawar University, said.

"I clearly remember the first day I went to school. I was wearing old clothes and two different slippers on my feet because my parents had no money to buy me books or a school uniform. But Maj Langlands encouraged me and taught me how to live a happy life.

"When I got this teaching job at Peshawar University, I took sweets for Maj Langlands. He distributed those sweets among girl students, saying he wanted every one of them to bring him sweets one day."

Maj Langlands only retired in his 90s, spending his last days in Lahore

Despite decades in the remotest parts of the country, Maj Langlands remained committed to the little things which made him English. Every morning, he would have porridge, poached eggs and two cups of tea.

He was equally dedicated to ensuring the school was as well-funded as possible, paying himself a meagre salary of less than $300 a month.

On his retirement, former pupils came together to ensure he was housed in a cottage at Aitchison, where he lived until his death on 2 January 2019.

As news of his death spread, people flocked to pay their tributes to the man who had helped shape their lives.

"If you ask me to name one pious man, I would say Geoffrey Langlands," former Aitchison student Ali Sibtain Fazli told the BBC.

It seems likely this assessment would please Maj Langlands, who revealed he had lived by one principle during an interview with the BBC in 2010.

"At the age of 12, I formed my own personal motto: be good, do good," he said. "And that I lived by all my life."

With additional reporting by BBC Urdu

- Published22 December 2018

- Published25 November 2018

- Published2 September 2018

- Published24 June 2018

- Published26 May 2018

- Published18 March 2018

- Published25 March 2018

- Published8 July 2018