Afghanistan war: What could peace look like?

- Published

The Taliban now control more territory in Afghanistan than at any point since 2001

For the first time in 18 years, the US government seems serious about withdrawing its forces from Afghanistan and winding up the longest war in its history.

Since October, US officials and representatives of the Taliban have held seven rounds of direct talks - aimed at ensuring a safe exit for the US in return for the insurgents guaranteeing that Afghan territory is not used by foreign militants and won't pose a security threat to the rest of the world.

A US-led military coalition drove the Taliban from power in 2001 for sheltering al-Qaeda, the militant group behind the 9/11 attacks.

A rare consensus about resolving the conflict peacefully, both inside and outside Afghanistan, means peace has never been so close. During a visit to Afghanistan in late June, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the Trump administration was aiming for "a peace deal before September 1st".

But the US-Taliban talks in Qatar's capital, Doha - as well as intra-Afghan dialogue involving the insurgents and some Afghan officials - are only the first phase of a complicated process with an uncertain outcome - and there are many hurdles to overcome.

Is peace with the Taliban possible?

Does there need to be a ceasefire?

While the US has reversed its refusal to talk directly to the Taliban, intense fighting and unprecedented numbers of airstrikes by the US and Afghan militaries are still going on all over the country. And while the Taliban negotiate they now control and influence more territory than at any point since 2001.

The war in Afghanistan is now the deadliest conflict in the world, causing more casualties than the fighting in Syria, Libya or Yemen.

Patterns of violence have changed dramatically in recent years. The vast majority of those being killed and injured now are Afghans - civilians, police and soldiers, and Taliban fighters.

In January, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani said more than 45,000 members of the country's security forces had been killed since he became leader in late 2014. Over the same period "the number of international casualties is less than 72", he said.

In February, the UN said civilian deaths reached a record high in 2018. It said more than 32,000 civilians had in total been killed in the past decade.

Taliban fighters are also regularly killed in large numbers in airstrikes, night raids and ground fighting.

Given the continued stalemate with the insurgents, US President Donald Trump is keen to end the war, which, according to US officials, costs about $45bn (£34bn) annually. His indication to withdraw most or all of his 14,000 forces in the near future caught everyone by surprise, including the Taliban.

There are also nearly 1,000 British troops in Afghanistan as part of Nato's mission to train and assist the Afghan security forces.

President Trump is considering withdrawing many of the US troops still in Afghanistan

But even if the US and the Taliban resolve their major issues, the Afghans themselves will need to sort out a number of key internal issues - including a ceasefire, dialogue between the Taliban and the government, and most importantly, the formation of a new government and political system.

Ideally, a ceasefire would precede presidential elections later this year and the Taliban would take part - but the latter seems unlikely.

Without a full or even partial ceasefire, there are fears that poll irregularities and a possible protracted political turmoil over the results could undermine any peace process and may increase political instability.

Can power be shared, and if so how?

There are a number of options and scenarios.

First of all, a decision will need to be taken by all major players on whether presidential elections, already postponed to late September, take place as planned.

If they do, a new government in Kabul could negotiate terms with the Taliban, unless a peace deal had been reached before the vote. Whether that government served a full term or held power on an interim basis while intra-Afghan power-sharing options were discussed is unclear.

But elections could also be further delayed or suspended - and the current government's term extended - while a mutually agreed mechanism to establish a new government, acceptable to all sides including the Taliban, is sought.

Will the Taliban end up back in government?

Creating a temporary neutral government or a governing coalition, that could even include the Taliban, is another option being looked at in this scenario.

A loya jirga - or grand assembly - of Afghans could also be called to choose an interim government which would hold elections once US troops have left and the Taliban has been reintegrated.

The BBC was given exclusive access to spend a week with ambulance workers in Afghanistan.

An international conference similar to the one in Bonn, Germany, in 2001 is another suggestion to help chart a future course for the country.

It would include Afghan players, major powers and neighbouring states - but this time also with the participation of the Taliban.

Several Taliban leaders have told me they need time to enter mainstream Afghan society and prepare for elections.

Would former enemies be able to work together?

There will be very difficult issues to surmount after a conflict that has left hundreds of thousands of casualties on all sides, including government forces, insurgents and civilians.

For example, the Taliban do not accept the current constitution and see the Afghan government as "a US-imposed puppet regime".

So far President Ghani's administration has not been involved in direct talks with the insurgents who refuse to talk to a government they don't recognise.

The Taliban have dismissed the government of Ashraf Ghani as a puppet of the US

Therefore, given the internal rivalries and diverse agendas of various local actors, the intra-Afghan phase of the peace process might prove more difficult than the US-Taliban talks.

However, there are positive signs.

Two rounds of intra-Afghan dialogue took place in Moscow earlier this year when Afghan politicians including ex-president Hamid Karzai, former commanders and civil society members, including women, met Taliban representatives to discuss ending the war.

A third such meeting took place in Doha in July, in which several officials currently serving in the Afghan government also participated, albeit in a "personal capacity". It is hoped that such meetings will eventually pave the way for formal peace talks between the Taliban and other Afghans, including the government.

A number of Afghans fear that sharing power with the Taliban could see a return to the group's obscurantist interpretation of Islamic justice. They are concerned that various freedoms, notably certain women's rights, could be lost.

The Taliban banned women from public life when they were in power in the 1990s, and their punishments included public stoning and amputations.

What if talks don't lead to peace?

Since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, there has been a long list of unfulfilled agreements and failed attempts aimed at ending the war in the country.

At least 45,000 Afghan police and soldiers have died over the past four years

Several scenarios from the past could be repeated this time round.

A US pullout, with or without a peace deal, might not automatically result in the sudden collapse of the government in Kabul.

The war could continue and the government's survival would largely depend on financial and military assistance from foreign allies, especially the US, and the unity and commitment of the country's political elite.

When Soviet forces withdrew in 1989, the Moscow-backed government in Kabul lasted for three years.

The Taliban are still openly active in about 70% of Afghanistan

But its collapse in 1992 ushered in a bloody civil war, involving various Afghan factions supported by different regional powers.

If issues are not handled with care now, there is a risk of a re-run of these two scenarios.

The Taliban, who emerged out of the chaos of the civil war, captured Kabul in 1996 and ruled most of Afghanistan until the US-led invasion removed them from power in 2001.

They could try to capture the state again if a deal is not reached this time round, or one fails.

What would chaos look like?

The current peace efforts could see the Taliban participating in a new set-up in Afghanistan.

This would mean the end of fighting and the formation of an inclusive Afghan government - a win-win for Afghans, the US and regional players.

But the alternative is dire - a probable intensification of conflict and instability in a country strategically located in a region with a cluster of major powers including China, Russia, India, Iran and Pakistan.

Another round of chaos could well result in the emergence of new violent extremist groups.

Afghans and the rest of the world would have to deal with a possible security vacuum in which militant groups such as al-Qaeda and Islamic State found fertile ground.

Increased production of drugs and the overflow of refugees would pose serious challenges not only to Afghanistan but also to the whole region and the rest of the world.

How could it be avoided?

History shows that starting negotiations and signing deals does not guarantee that conflicts will be peacefully resolved.

These steps are only the beginning of a complicated and challenging process - implementation of what's on paper is even more important.

The biggest challenge for Afghanistan would be the creation of verifiable enforcement mechanisms in any post-deal scenario.

The Taliban have had a political office in Doha since 2013

Given the history of conflict in the country, the current opportunity could be easily squandered if the process is taken in the wrong direction by one or more of the local or foreign actors.

Therefore, international guarantors and a framework involving the region and the key international players are needed to co-ordinate efforts for peace and deter and prevent spoilers from sabotaging the process.

There's a rare opportunity to resolve four decades of war - handle it with care, or risk facing the consequences.

Who is representing the Taliban?

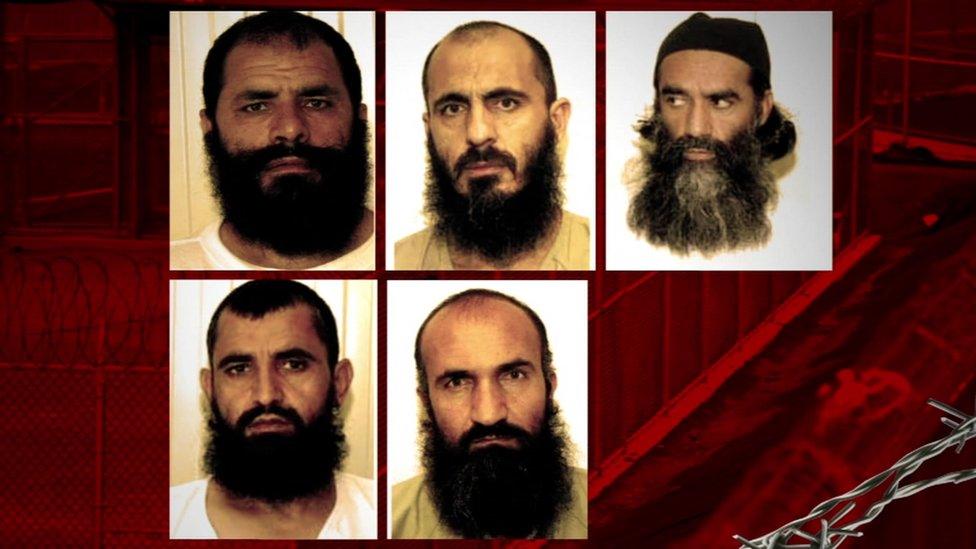

The "Guantanamo Five" were released by the US without being charged with any terror-related crime

The 14-member Taliban negotiating team also features the "Guantanamo Five" - former high-ranking officials captured after the fall of the regime and held for nearly 13 years in the controversial US detention camp.

They were sent to Qatar in a 2014 prisoner exchange involving Bowe Bergdahl, the US soldier captured by insurgents in 2009.

They are (clockwise from top left in photo above):

Mohammad Fazl - the Taliban's deputy defence minister during the US military campaign in 2001

Mohammad Nabi Omari - said to have close links to the Haqqani militant network

Mullah Norullah Noori - a senior Taliban military commander and a former provincial governor

Khairullah Khairkhwa - served as a Taliban interior minister and governor of Herat, Afghanistan's third largest city

Abdul Haq Wasiq - the Taliban's deputy head of intelligence

Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, a senior Taliban political figure and former head of its political office in Qatar, is leading the group's negotiating team.

In an interview with the BBC in February, he said a ceasefire would not be agreed until all foreign forces were withdrawn from Afghanistan.

Also present in Qatar is Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban's deputy head for political affairs and one of the group's co-founders, who was released from prison in Pakistan last October after spending nearly nine years in captivity.

- Published27 January 2019

- Published21 January 2019

- Published31 January 2018

- Published28 August 2021

- Published14 September 2018

- Published25 April 2017

- Published12 August 2022

- Published21 January 2019

- Published10 March