The DMZ 'gardening job' that almost sparked a war

- Published

Hundreds of troops were mobilised as a group of engineers drove in to chop down the tree

In August 1976, North Korean soldiers attacked a group of US and South Korean men trimming a poplar tree in the heavily-guarded zone that divides the two Koreas.

Two US officers were bludgeoned to death with axes and clubs.

After three days of deliberations going all the way up to the White House, the US decided to respond with a colossal show of force.

Hundreds of men - backed by helicopters, B52 bombers and an aircraft carrier task force - were mobilised to cut back the poplar.

Six of the men who took part told the BBC about their part in the most dramatic gardening job in history.

A small neutral camp called the Joint Security Area (JSA) lies on the border between North and South Korea, in the area known as the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ). Both were created under the terms of the armistice signed in 1953 which ended the Korean War.

The JSA - also called Panmunjom, or the Truce Village - is where negotiations between both sides take place. Most recently, it was where US President Donald Trump stepped into North Korea, becoming the first US leader to do so.

But in 1976, guards and soldiers from both sides could wander all around the small zone. North Koreans, South Koreans and US guards would mingle together.

Bill Ferguson was just 18 years old in August 1976. He was part of the US army support group in the JSA, under the command of the popular Captain Arthur Bonifas.

"Capt Bonifas really wanted us to enforce the terms of the armistice," Mr Ferguson says. "We were encouraged to intimidate the North Koreans into allowing the full freedom of movement within the JSA."

At the time, US soldiers were only allowed to serve in the JSA if they were over six feet (1.83m) tall, Mr Ferguson says, as part of this intimidation.

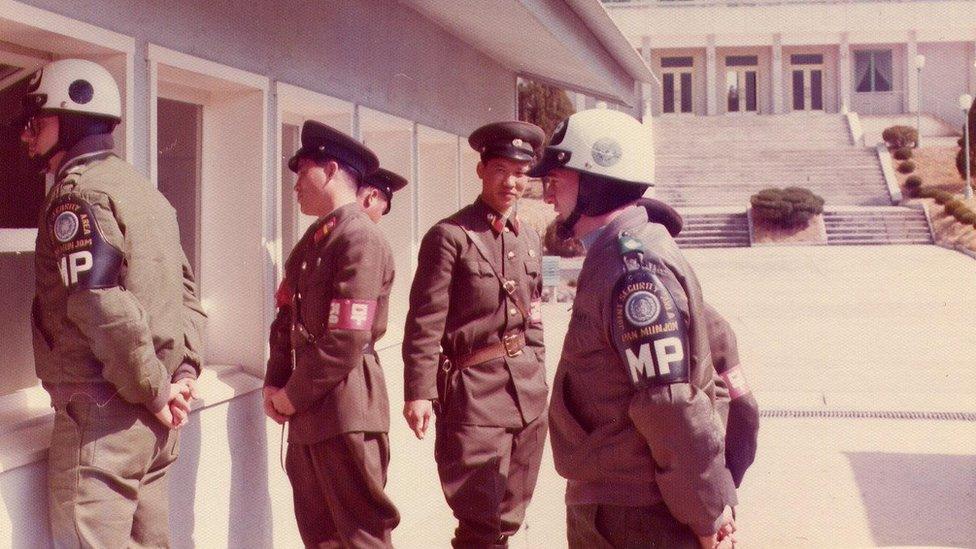

Men from North Korea and the US mingle in the JSA, with the Panmungak pavilion in the background

"We didn't get along with them at all," Mr Ferguson remembers, although he admits that occasionally North Korean guards would trade propaganda from their country for Marlboro cigarettes.

Strict rules limited the number of guards from both sides and the weapons they could carry. Troops from one side would try to antagonise the other, which often led to violence. While Mr Ferguson was there, one US guard had his arm broken by North Koreans after he accidentally drove his jeep behind their main building, the Panmungak pavilion.

US Lieutenant David "Mad Dog" Zilka meanwhile encouraged men to go out on patrol carrying big sticks, to bang on the walls and windows of North Korean barracks and to use as weapons if need be.

"Zilka would take us out on these clandestine patrols," says Mike Bilbo, a platoon mate and friend of Bill Ferguson's in the JSA. "Once or twice we caught a North Korean where they weren't supposed to be and kind of beat him up a little bit - not too bad."

Mr Bilbo says these aggressive actions on both sides may have prompted the incident over the tree. "But there's just no cause for them to do what they did."

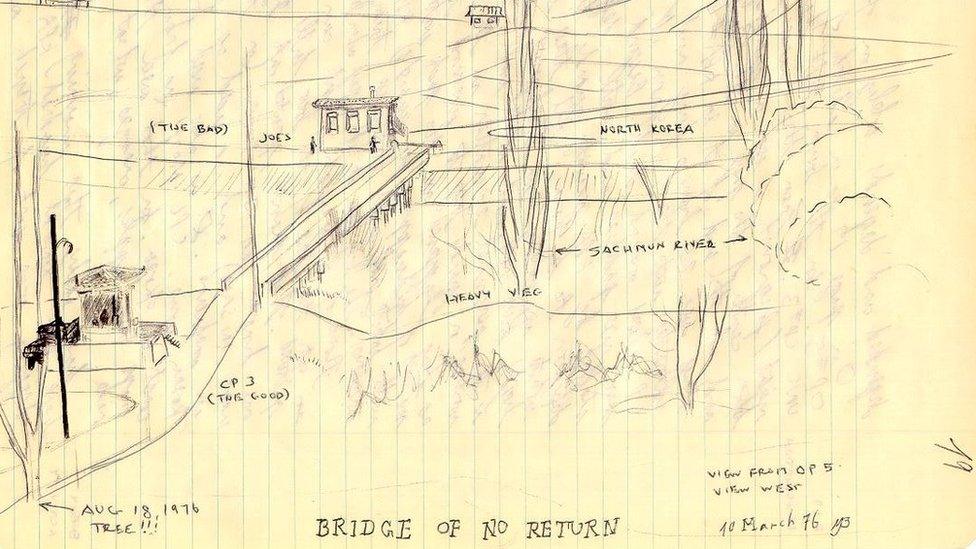

A sketch by Mike Bilbo in 1976 showing the Bridge of No Return separating North and South Korea, and the tree in the bottom left-hand corner

The branches of the poplar obscured the view between a checkpoint and an observation post. A team of US and South Korean men were ordered to prune it back.

On the first attempt, North Korea objected, claiming any landscaping work required permission from both parties. Heavy rain thwarted the second try.

Capt Bonifas - in the final days of his deployment in Korea - decided to monitor the third attempt personally, on 18 August.

A group of North Koreans appeared, demanding they stop cutting the branches. When Capt Bonifas ignored them, the North Koreans attacked - using clubs and axes wrenched from the gardening party to bludgeon the captain and US Lieutenant Mark Barrett to death.

Sirens went off throughout the DMZ and troops were put on high alert. Word of the attack quickly reached Washington DC, where Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called for an attack on the North Korean barracks, external to ensure "a high probability of getting the people who did this".

"They have killed two Americans and if we do nothing, they will do it again," he told a briefing. "We have to do something."

In the end, Kissinger was overruled. While military and political leaders debated how best to respond, they all agreed on one thing: the tree had to go.

Commanders came up with a plan to prune the tree back using a massive show of force. It was designated Operation Paul Bunyan - named after a giant lumberjack in US folklore - and scheduled for 21 August.

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger discussed the North Korea incident with President Gerald Ford

How the North Koreans might respond to this force though was another concern.

Wayne Johnson was a 19-year-old US private with the 2nd Battalion 9th Infantry, stationed at Camp Liberty Bell just outside the JSA. He drove his commanding officer to a briefing the night before the tree-cutting operation, and saw a lieutenant ask what would happen to his unit.

"I watched the officer turn around with this piece of chalk and draw an X through our unit designation on the chalk board, then turn back around and say, 'Any more questions?'" Mr Johnson says.

The teenager was tasked with rigging Camp Liberty Bell with explosives that night to destroy the base in case the North Koreans attacked and tried to capture it. Then he drove up to meet the rest of his unit at the JSA, passing through US and South Korean checkpoints as he went.

"I thought that was kind of funny," he says. "At the DMZ gates I had to go through a checkpoint there. I'm thinking, what the hell, don't these guys know that things are going to happen?"

'We were prepared not to come back'

Bill Ferguson and Mike Bilbo spent the night preparing for their own mission - driving in and securing what is known as the Bridge of No Return to prevent North Korean forces driving into the JSA and interfering with the tree cutting.

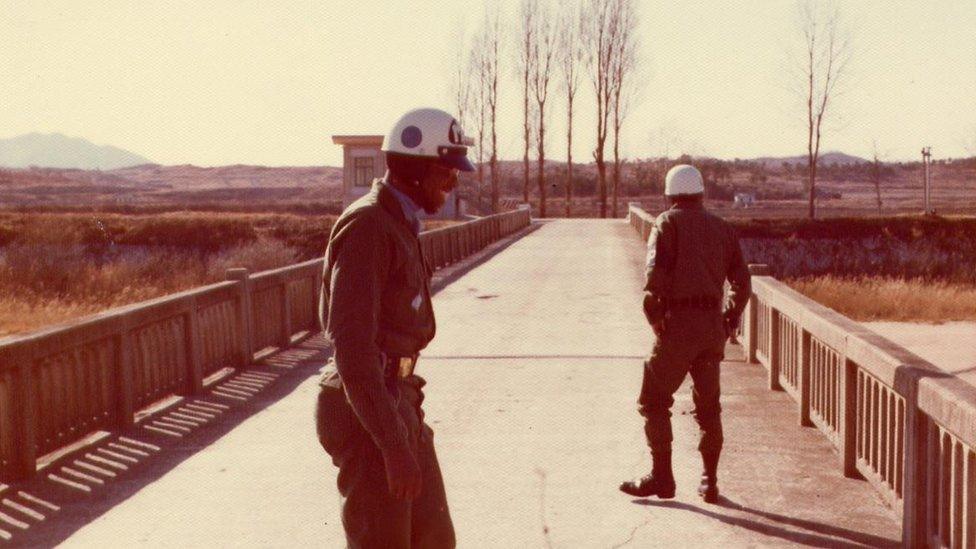

The Bridge of No Return in the JSA crosses the Military Demarcation Line between North Korea and South Korea

"A couple of guys got sick - the tension, the nervousness of it," Mr Bilbo says. "Everybody's on pins and needles. And when we pulled out from our camp, there's Cobra helicopters hovering just off the ground getting ready to take off.

"I looked down the road and here is all these as far as I can see truckloads of soldiers. It's an invasion force of some kind."

Ted Schaner was a 27-year-old captain with the 2nd Battalion 9th Infantry, and one of the men in the helicopters hovering overhead as the soldiers drove in towards the tree.

"It was an impressive line up there," he says. They, too, were unsure whether war was about to break out. "We were, of course, hoping it wouldn't, but I felt... we were prepared if that's what was going to happen. I was proud of my soldiers."

Alpha company of the 2nd Battalion 9th Infantry - Wayne Johnson's company - remained on the ground.

"We were prepared not to come back," says Joel Brown, then a 19-year-old private with Alpha Company. "It felt kind of surreal... We've been here since 1950 and it's all going to go down over this tree."

US troops moved into the JSA early in the morning to cover the engineers coming in to cut back the tree

Bill Ferguson and Mike Bilbo's platoon arrived just as the fog was lifting. Their truck driver reversed onto the Bridge of No Return to block the crossing, while the men jumped out armed only with pistols and axe handles.

"Almost immediately a dump truck comes up, and it's got engineers in it," says Mr Bilbo. "I've never seen chainsaws so long."

Charles Twardzicki of the 2nd Engineer Battalion had spent the night practising to use the tools. The 25-year-old sergeant had suggested bringing in heavier equipment to take the tree down, but officers feared it would be too difficult to speedily get them out if the North Koreans tried to intervene - leaving them to cut back the branches by hand.

"We have to use a ladder to get up into the tree," he says. "We got one guy on the headache board [behind the truck's cab] cutting one, and I'm cutting another. His chainsaw is about where my head is."

As the engineers chopped, the troops watched North Korean forces arrive in trucks and buses.

"We can see the North Koreans across from us setting up machine guns," says Mike Bilbo. "I'm looking around where I'm going to go when the artillery comes in. In fact, all the artillery - ours and theirs - was zeroed in on us."

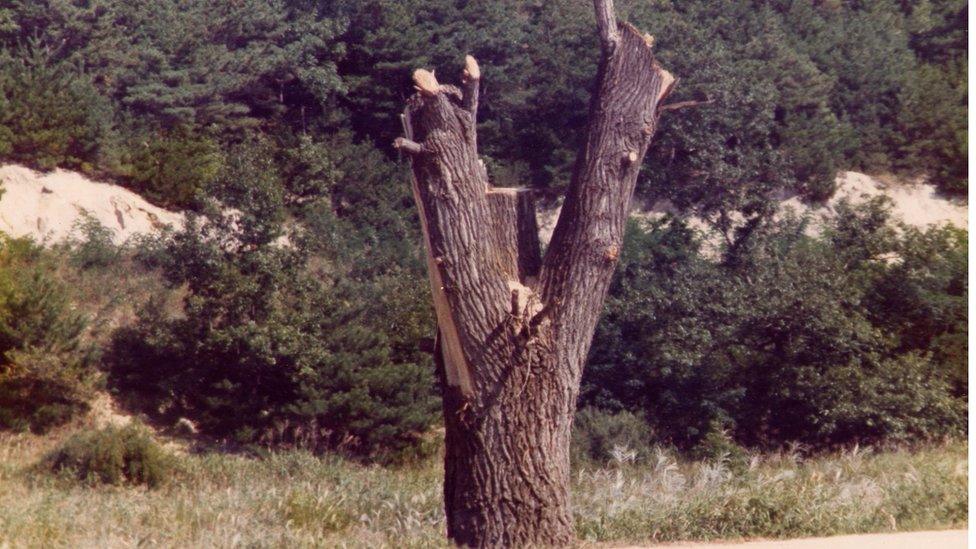

US engineers pruned the tree with chainsaws, leaving only the trunk

Several US soldiers remember they and the South Korean special forces who accompanied them had sneaked heavy weapons into the area under sandbags on the floor of their trucks. Some South Koreans even strapped claymore mines to their chests and held the detonators in their hands, goading the North Koreans to attack.

"I understood some of the bad words in Korean and it was a lot of bad words, let me tell you," says Wayne Johnson, who was standing just yards away from Bill Ferguson and Mike Bilbo during the tree cutting.

But the North Koreans did not intervene. Once the branches were cut down, the US and South Korean forces quickly withdrew from the JSA - although other forces in the DMZ remained on alert. The entire operation was over in less than 45 minutes.

'A pretty poor trade'

"Everybody was jazzed up," Mike Bilbo says. "Symbolic things bother the North Koreans more than the actual."

"One day I went out and sawed a couple pieces of the branch... Everybody's got a piece of that damned tree," he says.

Since 2018, North and South Korea have demilitarised the JSA, removing all mines and guard posts

Soldiers felt they had made the North Koreans lose face, something they knew would enrage them. But others remained angry.

"I felt that we got the worst part of it," says Charles Twardzicki. "We were just trimming the tree and you killed a couple of our officers - so we cut it down... I thought it was a pretty poor trade."

"We didn't want to be the ones responsible for starting a whole new war, but we were also dying for the chance to extract some blood," says Bill Ferguson.

Rules in the JSA changed shortly after Operation Paul Bunyan. North Koreans were separated from UN forces with the small concrete barrier that President Donald Trump stepped over in July - putting an end to the mingling and intimidation tactics.

President Trump: "Stepping across that line was a great honour"

"That was a major letdown," Bill Ferguson says. "North Korea was never that fond with that arrangement, it being a neutral area... To me and several others enforcing the line through the JSA, it was basically a capitulation."

However, a rare expression of regret from then-North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung about the deaths of the US soldiers on the day of the tree cutting made many realise they had sufficiently shocked the country with the vast display of US firepower.

Troops at Camp Liberty Bell and the JSA stayed on high alert after the operation, in case of retaliation. It was weeks before the men could return to their regular routine.

"Nobody had gone down to the [local town] for over a month and I think that some of those bars were about to go bankrupt," says Wayne Johnson. "It was kind of, okay, business as usual, let's go back."

- Published1 July 2019

- Published10 March 2019

- Published18 January 2019

- Published5 March 2014