Singapore election: Does the political shake-up change anything?

- Published

Singapore may be one of the world's wealthiest and "smartest" countries, but there's one thing it has never had, until now - an official opposition party. After a recent surprising election, change is in the air, writes the BBC's Sharanjit Leyl.

On 10 July, voters wearing masks stood in socially distanced queues in Singapore to cast their ballot, with a pandemic crisis and looming recession on their minds

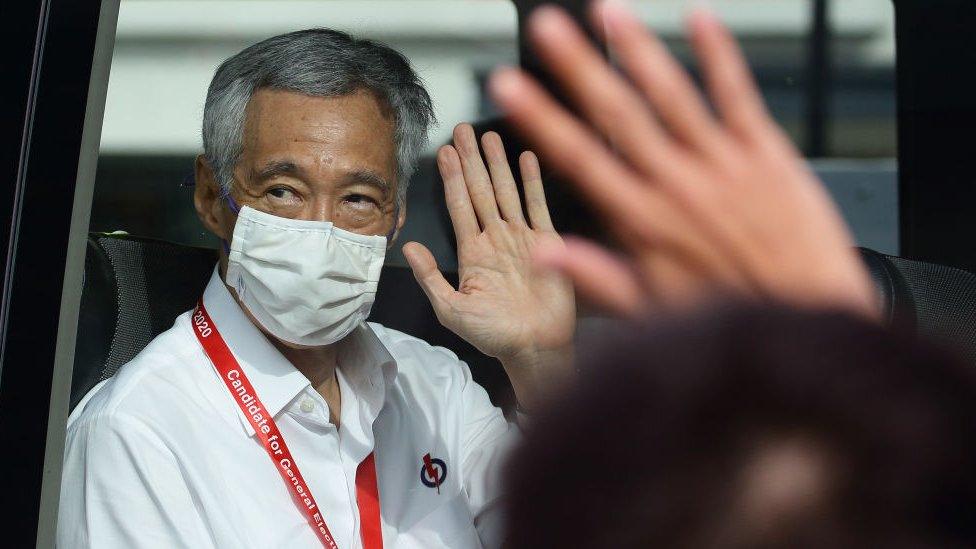

The election - one of a handful globally during the pandemic - saw the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) return to power yet again, but to the surprise of many, with a reduced majority.

The biggest opposition group, the Workers' Party, had its best result to date, winning 10 seats.

Backing an opposition party in Singapore has largely been seen as a protest vote. And until now, the few opposition MPs have been a relatively powerless voice in parliament.

While campaigning, the Workers Party leader Pritam Singh had in fact assured voters his party didn't even have ambitions to govern - they just wanted to be able to provide a check and balance to the PAP.

Pritam Singh is now Singapore's official Leader of the Opposition

But in response to the WP's unexpected success, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong gave Mr Singh the title of Official Leader of the Opposition - the first time any opposition leader in Singapore has been considered relevant enough to hold the post.

It means Mr Singh is entitled to state funding for staff and resources, making his party a genuine opposition.

In a statement to the BBC, Mr Singh points out that the party's numbers in parliament are still small and "far short of the one third required to break the ruling party's parliamentary supermajority".

But it marks a major shift in politics and could be a step towards breaking the PAP's complete dominance of Singaporean politics.

A one party state?

Singaporeans have never experienced a time where the PAP was not in charge - they have won every election since Singapore was granted self rule by the British in 1959.

The party was co-founded by Lee Kuan Yew, considered by many to be the architect of Singapore's rapid economic success.

PM Lee Hsien Loong's father, Lee Kuan Yew, is considered to have been responsible for shaping Singapore

So aligned is the party with "LKY" that his death shortly before elections in 2015 saw a surge of support for the PAP. His son, Lee Hsien Loong, is the current prime minister.

While credited with spearheading Singapore's success, the PAP has also been accused of implementing draconian policies such as strictly regulating public assembly and the media.

A "fake news" law implemented last year - which allows government ministers to order amendments to online posts it deems false and harmful to the public interest - has heightened concerns of yet more limits to freedom of expression and increasing self-censorship.

During the recent elections, a number of media organisations and sites carrying comments from an opposition candidate fell victim to the law.

And while Singaporean politics mirrors the first-past-the-post Westminster model, there are key differences that make it harder for opposition parties.

MPs contest for constituencies that vary in size and the larger ones are not represented by an individual MP, but by a team of up to five MPs - called Group Representative Constituencies (GRCs).

A previous rally in 2015 showed considerable support for the PAP

The system was introduced in 1988 as a way to include more representation from Singapore's Malay, Indian and other minority groups in the predominantly Chinese city - so parties could "risk" running one or two minority candidates.

But until recently, opposition parties have not had the resources to recruit enough skilled and experienced people to genuinely contest these larger constituencies. When the Workers' Party won the Aljunied GRC in 2011, it was considered a shock win and a breakthrough for opposition voices. This year, they have picked up another large GRC constituency.

And, in what has been ranked the world's most expensive city, it's costly to even stand in an election.

Candidates must deposit S$13,500 ($9,700: £7,700) to contest and need to win more than one-eighth of total votes to get it back.

The electoral divisions of constituencies are often changed to reflect population growth - opposition parties say this is not done transparently and amounts to gerrymandering, something the government has always denied.

On top of this, there are long-standing allegations that PAP-held areas tend to be allocated more funds for the improvement and maintenance of facilities than opposition constituencies, which discourages swing voters.

The PAP declined a BBC interview request on these issues.

All of this has meant that while oppositions parties are vocal and active, it's been almost impossible for them to gain ground.

'A freakish state of affairs'

Pritam Singh campaigned on the premise that the government is more responsive to people's concerns when it loses elected seats, as they did in 2011, when the PAP suffered its worst election result and went on to change policies around immigration, a major source of consternation for many voters.

His party's success has been largely attributed to young and first time voters, who make up about a third of the electorate and were keen to see Singapore develop as a democracy. What were seen to be PAP attacks against opposition candidates also put off the electorate.

Supporters of the Workers Party came out in celebration

Eugene Tan, a regular commentator on politics, and an associate professor of law at the Singapore Management University, says the election result makes it clear that voters - especially younger one - are starting to view one-party dominance as "a freakish, even unfair, state of affairs".

The PAP's "instinctive quest for political dominance" is " increasingly at odds with the electorate's growing belief that political competition and diversity… are critical ingredients of a robust system of good governance", he told the BBC.

Viswa Sadasivan, a political blogger and academic, said this election was a game-changer in Singaporean politics.

Like Mr Tan, he previously served as a "nominated MP" - seats handed to non-partisan individuals to provide alternate viewpoints.

These nominated posts were created in 1990 at a time when there were barely any elected opposition members in parliament and the PAP would often win elections even before polling day because there were so few seats contested.

The election result, he told the BBC, was "a slap-in-the-face for PM Lee Hsien Loong, who asked for a strong mandate from the people".

They both contend that institutionally, the odds are still stacked against the opposition parties after many years of PAP dominance.

But the ruling party will be under pressure now to review and revoke systemic political policies and practices that are unfair, according to Mr Viswa.

Viswa Sadasivan says it will be easier now for 'critical voices' to be heard

Mr Tan says the PAP government may finally be coming to terms with the fact that "public perceptions" of "an un-level playing field is a growing source of grievance for voters".

"That is hurting the ruling party ultimately," he said.

According to both Mr Tan and Mr Viswa, with louder voices now in the opposing camp, politics will have to take a more collaborative tone - especially given recent dismal economic figures.

Ultimately most Singaporeans agree, whichever side they voted for, that the outcome of this election is a sign their country's democracy may finally be maturing.

- Published10 July 2020

- Published6 July 2020

- Published10 April 2020

- Published9 May 2019