Afghan interpreters rejected for resettlement fear death after UK exit

- Published

UK and US forces will leave Afghanistan by September

AJ has been scared to leave his home in Kabul for months - he fears the Taliban want him and his family dead.

Now in his early 30s, he is one of hundreds of Afghans who worked with British forces as interpreters and support staff, and who may now be targeted by the militants as a result. They fear the risk will only increase when foreign forces pull out this year.

But AJ (who cannot reveal his name for fear of being attacked) has been repeatedly rejected for resettlement under UK government schemes to help interpreters such as himself and their families resettle in the UK.

British officials say he was dismissed for smoking in his accommodation. Interpreters who were fired are not eligible for resettlement.

AJ says that he was not told that he was being dismissed when he stopped working with the army, and is incredulous at the justification for blocking his move to the UK.

"It cannot be that serious that it can cost me my life," he says. "I know that I am in real danger. I can't even take up a job. I don't go to public spaces."

Dismissals 'for HR management'

Some 1,010 interpreters - one in three - were dismissed by the British between 2001 and 2014 for "disciplinary reasons", external without the right to appeal, government figures show.

Some 2,850 interpreters have worked with British forces in Afghanistan

But retired Colonel Simon Diggins, formerly the British attaché in Kabul and now a campaigner for Afghan interpreters, says many of those dismissals were for trivial reasons.

"Whilst some of those who were dismissed did things that were disgraceful, there were a very large number of people who were dismissed for very minor or administrative issues," he told the BBC.

"There is a suspicion that the dismissals were used for HR management. There is very little evidence for why people were dismissed. What we're asking for is that their cases are all reviewed."

The Ministry of Defence says it strongly rejects the idea dismissals were used "administratively".

'They know who I am'

AJ's fears have only grown following last week's announcement that American and British forces will leave Afghanistan by 11 September, at a time when the Taliban is growing in strength across the country.

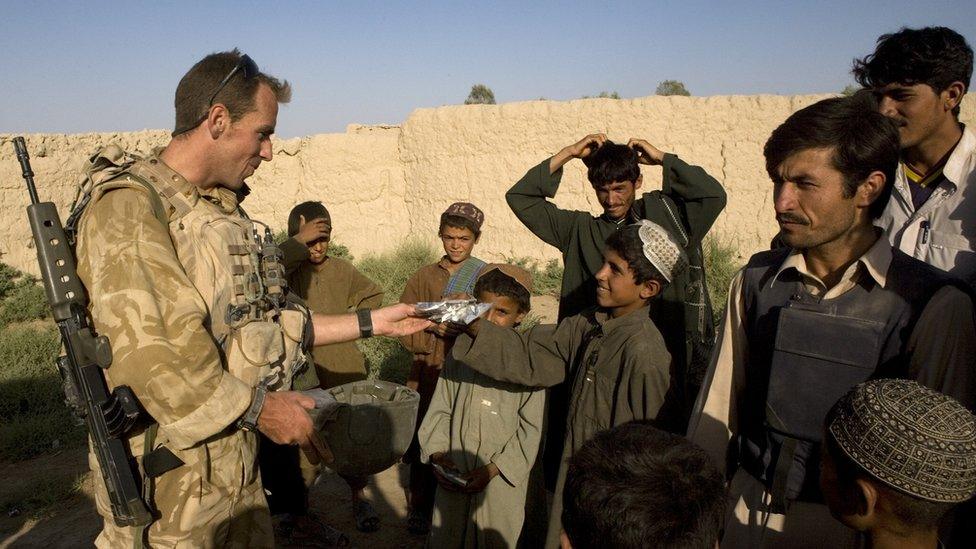

AJ was recruited by the British when he was a teenager. Interpreting enemy messages for a parachute regiment and the Royal Marines, he took part in missions across Helmand Province in southern Afghanistan, where the Taliban had an entrenched presence. A commanding officer praised his "hard work and dedication" in a service certificate.

"AJ" is scared to leave his home in Kabul after receiving death threats from the Taliban

When his regiment faced a Taliban attack in the southern town of Sangin, AJ says he was forced to flee without his personal belongings - including his identity card. He believes the Taliban uncovered them and learnt of his work for the British.

Since he stopped working with the army, AJ says his family - he is married with three children - has received three letters containing death threats from the Taliban. "I know that they know who I am," he says. "And it's making me sick."

Over the past six years AJ has applied to the resettlement scheme several times, but has been rejected on each occasion.

After an application in December, he received an email from officials running the resettlement scheme - seen by the BBC - telling him that he was "not eligible for relocation" because he had been dismissed for "possession of prohibited items" and "smoking in your accommodation".

When he applied again this month, he was rejected on the same grounds.

Another dismissed interpreter, "Ahmad", also had an application rejected this month.

"Ahmad" says he was dismissed for arriving late and has been rejected for relocation

He says he was fired for arriving late to work on three occasions in 2013. Since then, Ahmad says he has been threatened by the Taliban - even a neighbour in Kabul told him he would one day be killed as "an infidel".

"I've grown a beard and changed my clothes to protect myself," Ahmad says. "Coming late shouldn't cost you your life."

'Debt of gratitude'

Since announcing a resettlement scheme in 2013, the Ministry of Defence has extended the number of those who are eligible - but this still does not include any interpreters who were dismissed "unless in exceptional circumstances".

"We owe a huge debt of gratitude to interpreters who risked their lives working alongside UK forces in Afghanistan," a spokesperson for the Ministry of Defence told the BBC.

"Nobody's life should be put at risk because they supported the UK Government to bring peace and stability. We are the only nation with a permanent expert team based in Kabul to investigate claims from courageous local staff who are threatened as a result of their work with the UK."

So far, some 1,358 interpreters have been able to relocate to the UK, from a total of 2,850 interpreters and other staff employed by the UK military.

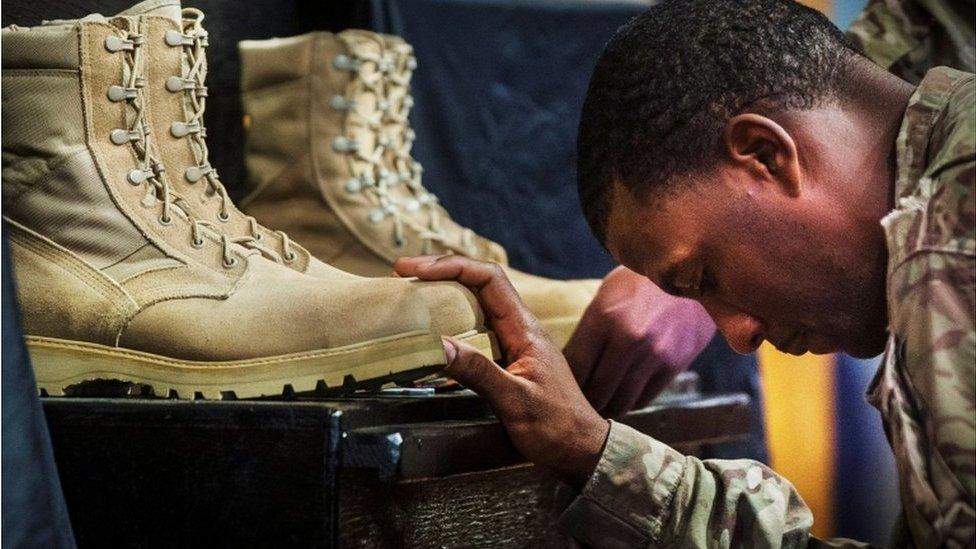

One of them is Eddie Idrees (not his real name), a former SAS interpreter who took part in hundreds of missions including parachute jumps and a break-in to a Taliban prison - experiences he has documented in a book, external. Of 18 friends who worked with US and British troops only he and a friend also now in the UK survived.

Former SAS interpreter Eddie Idrees has been resettled in the UK

All the others were either killed in action or later murdered by the Taliban.

Mr Idrees says he also fears for interpreters who have worked on military operations and remain in Afghanistan after the international pullout.

"When the British pull out of Afghanistan it will just let the Taliban target them easily," he said.

Even those who are eligible for the scheme face an application process that can last for up to 18 months, a delay that Mr Idrees says could put lives at risk.

"The day when British forces leave it is the day you will see a surge in violence. Once they leave, those areas that used to be safe, those provinces, won't be safe any more. And these interpreters are not going to be forgotten by the Taliban."

'Still waiting'

Col Diggins has called for an "emergency plan" to relocate interpreters as soon as possible.

"What really worries me is the scale and pace to get the people who deserve to come to this country given how the situation is worsening," he said. "It's taking 12 to 18 months to process paperwork. We don't have that much time."

The Ministry of Defence says it is currently looking at the cases of 84 former interpreters.

Among them is "Amir", who served for two years on the front line with British troops in Helmand where they came under regular attack from the Taliban. Since resigning in 2011, he says he has faced intimidation over his work with the British. He hasn't been able to see his family who live in Taliban-controlled territory in Logar Province, just outside Kabul.

Are the Taliban preparing for peace or more war?

Having been rejected twice, Amir is hopeful his third application will be successful. "I am waiting to hear good news," he said.

But he has felt "dread" since hearing the news the foreign troops would withdraw. "That is going to cause more of a problem for us. I feel a lot of risk these days. If you served as an interpreter who worked with the British you are staying at home."

The UK is not the only country working on schemes to help their former Afghan interpreters.

The US has a special visa programme for Afghans who have worked with its military. At least 89,000 individuals have been resettled through the scheme and 17,000 are still waiting for a result, according to the International Refugee Assistance Project.

Germany's defence minister has said it is her country's duty to protect Afghan staff when the German contingent leaves.

But for those who have so far not qualified for the schemes, the future is uncertain.

"I am going to try to make them trust me and see that my life is at risk," AJ said after hearing his fourth application had been rejected. "It's terrible. I'm still waiting."

Additional reporting by the BBC's Charles Haviland

- Published12 August 2022

- Published17 April 2021

- Published15 April 2021

- Published15 April 2021

- Published14 April 2021

- Published9 February 2017