Echoes of 1989 as foreign forces withdraw from Afghanistan

- Published

As the Taliban make rapid battlefield gains ahead of the US military pullout from Afghanistan, the question of who stays and who goes is once again at the top of foreign envoys' agendas.

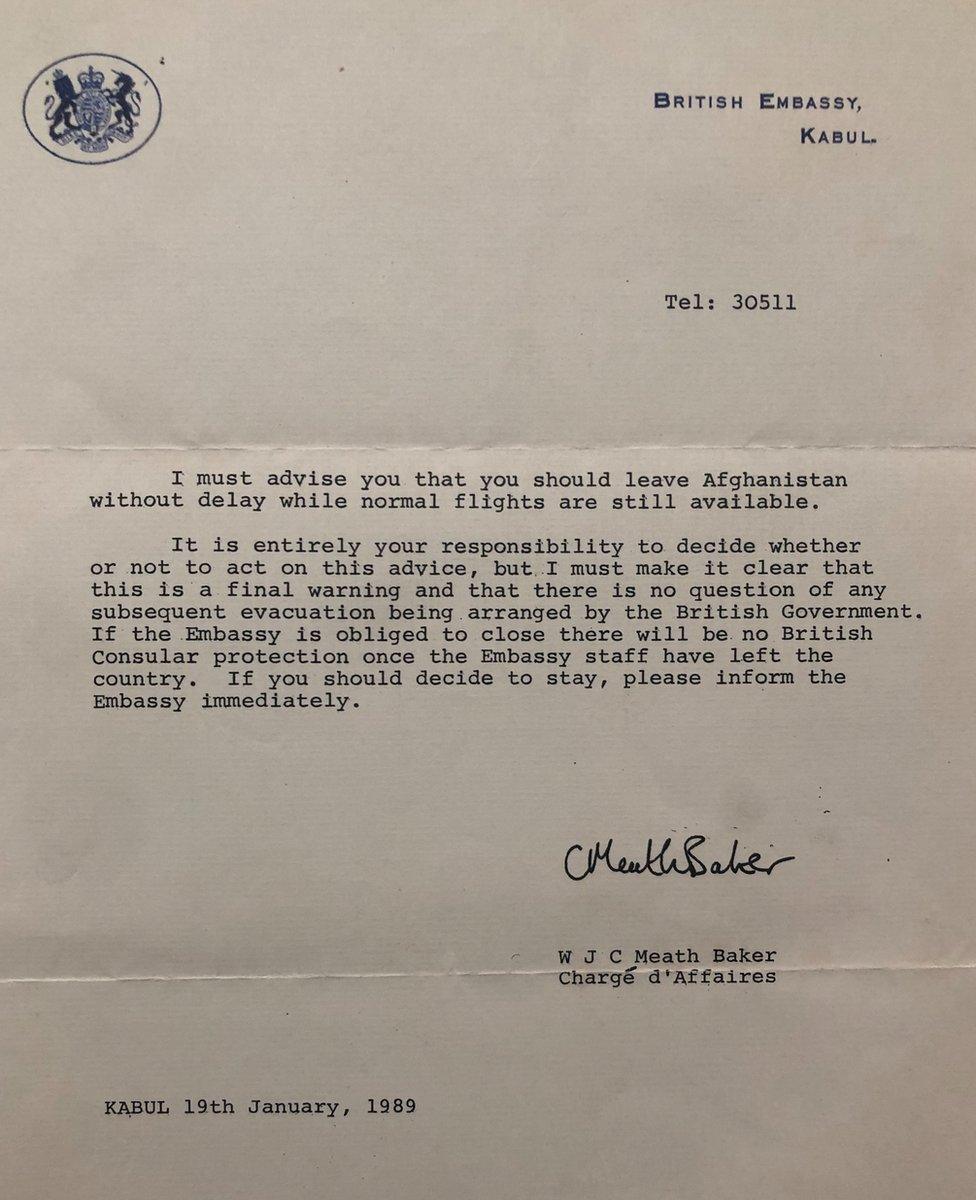

The "final warning" on fine notepaper was delivered to me in the depth of a harsh Kabul winter at the peak of a Cold War conflict. "I must advise you that you should leave Afghanistan without delay while normal flights are still available," advised the British chargé d'affaires.

Eleven days later, on a snowy 30 January 1989, we watched the US chargé d'affaires solemnly lower the stars and stripes in a simple ceremony freighted with political meaning. The last Soviet troops were pulling out within weeks, ending their disastrous decade-long Afghan engagement. An exodus of Western missions was meant to rattle the beleaguered Moscow-backed government.

Britain also shut its gates on its magnificent white stucco compound once hailed as the "finest in Asia".

"UK ministers felt that they had no choice but to follow suit even though our embassy staff were keen to stay put and carry on with the job," recalls Stephen Evans, a former British ambassador to Afghanistan who was then the Afghanistan desk officer in the British foreign office.

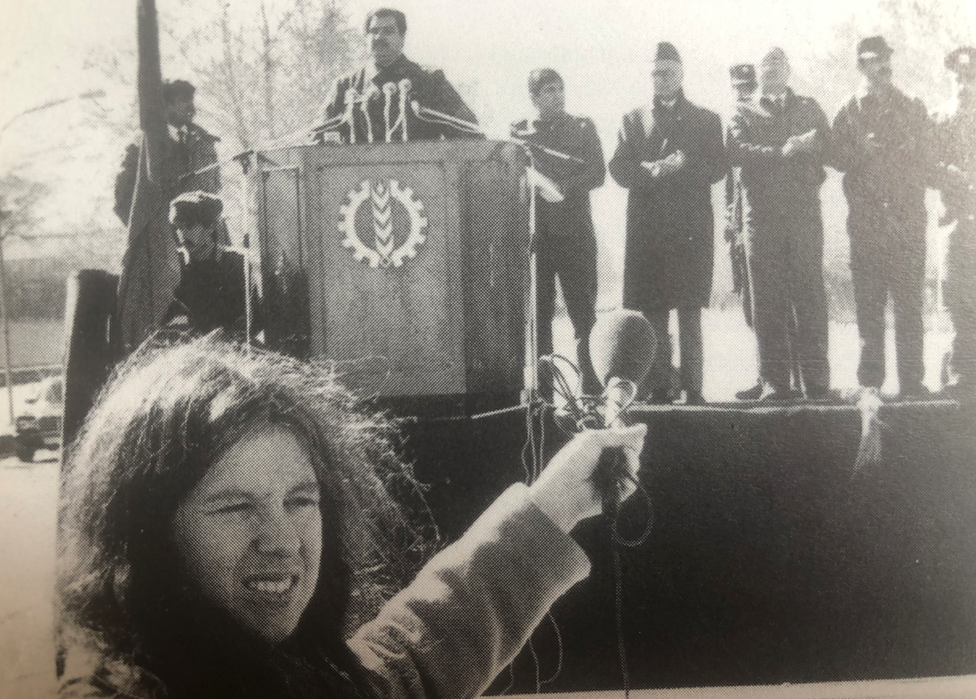

Lyse Doucet records Soviet-backed president Mohammed Najibullah speaking in 1989

Both Washington and London promised they'd soon be back, but their missions would stay shut until a US-led invasion in 2001 toppled the Taliban.

Now, as a nearly 20-year Nato military mission ends with the exit of foreign troops, the question of staying or going is back at the top of the envoys' agenda.

"We absolutely do not want to send a similar signal right now by closing our embassy, unless there is an overwhelming security reason to do so," emphasises Mr Evans in a sentiment widely echoed behind soaring blast walls and sharp coils of barbed wire now cocooning diplomatic and aid missions, as well as a multitude of other buildings in the capital.

But the faster than expected pace of the US-led pull out, the tumbling of districts to the Taliban at a surprising speed and scale, not to mention the dread of a highly infectious variant of Covid-19, has added a large lashing of unpredictability to this mix.

Evacuation plans are constantly updated, staff numbers have been steadily drawn down - driven by both Covid and security risks - and some bags are packed, just in case. There are days of calm, days of concern.

"All our capitals are interested in right now is security," laments one European diplomat. "For the last few months in Kabul we've all been discussing security because we're all so invested here and want to stay."

The last Belgian diplomats bid adieu this week and the Australians shut up shop in May. The French almost left and the British, like everyone else, constantly assess the situation.

Kabul watches closely as events unfold

Watching even more nervously are Afghans who assist anxious envoys, the interpreters who translated language and culture for foreign troops, and the many vulnerable Afghans surviving in a city plagued by incessant power cuts and endless aggravations, who watch the embassies' every move as an omen of what's to come.

"If the country is told enough times that it is destined for failure then what hope is there for embattled Afghans to fulfil an alternative?" asks Muqaddesa Yourish, a former deputy minister of commerce who is now an executive at a leading communications firm in Kabul.

There was upset among Afghans when the Australian government announced in May it was closing its Kabul embassy although it expressed hope the move would be temporary. This time, in a sign of the times, it was a tweet, not a letter, from the British embassy which urged all British nationals in Afghanistan leave "as soon as possible".

"It's unfortunately an international echo chamber and the world seems to be projecting their guilt of withdrawal in predicting the worst for us - a civil war," Ms Yourish adds with regret. Afghans are also anxious about the threats of intensifying war.

Yet again, the British are watching the Americans; most foreign missions are. The US says it's planning to keep hundreds of its troops on the ground to secure its embassy, as it does in many other places.

Even that is fraught with risk. This week, a Taliban spokesman reiterated to the BBC that any residual presence of foreign forces would be regarded as "an occupation army". The Taliban insist it's a violation of the US-Taliban deal which paved the way for this pullout.

"During negotiations with the US, all these topics came up for discussion and, ultimately, the US side agreed to withdraw all troops, advisers, trainers etc from the country," emphasises Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen when I ask him about this issue.

The Taliban, keen to enhance their international legitimacy, are keeping an eye on embassies too. Last month, when the EU's new special envoy for Afghanistan Tomas Niklasson raised security concerns with Taliban leaders based in Doha, they released a statement within hours that diplomatic and aid missions in the Afghan capital would be protected.

But not everyone is convinced that what one Western diplomat called "words from polished diplomats in Doha" would be respected by all Taliban field commanders. And while the Taliban want the world's envoys to stay in Kabul, they don't want them doing their job - supporting the government in power.

Some foreign missions now situated outside the sprawling high security compound known as the Green Zone are planning to shift inside its gates within gates within gates. Norway has agreed to continue operating a vital field hospital used by diplomats and aid workers until next spring, by which time it's hoped a civilian hospital will have been established. Most crucial of all is the international airport - vital for Afghans too - which can serve, in the worst-case scenario no one wants to see, as an evacuation route.

Hamid Karzai International Airport is now guarded by Turkish and US troops under Nato's legal umbrella. It's hoped that Turkey will continue this task through a bilateral agreement with the Afghan government.

But, even at this eleventh hour, difficult discussions with Ankara are in a tangle of political, security and legal issues, not to mention the stubborn Taliban edict. Nato officials express confidence a deal can be done.

Will Afghan special force commandos be a match for Taliban fighters?

So most embassies are now trying to signal that they're staying put.

"The US embassy in Kabul is open and will remain open," underscored a post on their Twitter account when media reports started surfacing of stepped-up evacuation planning.

"Embassies will remain in Kabul," emphasises a Western diplomat. "But we are in a sensitive period and monitor the situation daily. The security of embassy staff is paramount."

"The embassy to watch is the UK," remarks another diplomat in Kabul. "It's not just Western missions. Even the Chinese ambassador is indicating he wants to increase dialogue on security issues."

The British compound, just inside the Green Zone, is larger than some missions, but is much closer in size to many others. So it's being seen as a bellwether.

And all eyes - Afghan and foreign - are on a fast-changing security situation across the country.

"A lot of the districts the Taliban have taken are irrelevant in strategic terms, but important for propaganda purposes," assesses Tamim Asey, a former Afghan deputy defence minister who now heads the Institute for War and Peace Studies in Kabul. "The next fighting season will be the battle for cities."

In a conflict where the narrative about what is happening on the ground can matter as much as the events, there's an effort now among envoys to try to stay calm, and carry on, as hard as that can be.

Former Afghan president Hamid Karzai: Nato failed to defeat extremism

Related topics

- Published5 July 2021

- Published26 June 2021

- Published22 June 2021