Afghanistan war: Taliban back brutal rule as they strike for power

- Published

Taliban fighters in Balkh and elsewhere have made a rapid advance in recent weeks

The Taliban fighters we meet are stationed just 30 minutes from one of Afghanistan's largest cities, Mazar-i-Sharif.

The "ghanimat" or spoils of war they're showing off include a Humvee, two pick-up vans and a host of powerful machine guns. Ainuddin, a stony-faced former madrassa (religious school) student who's now a local military commander, stands at the centre of a heavily-armed crowd.

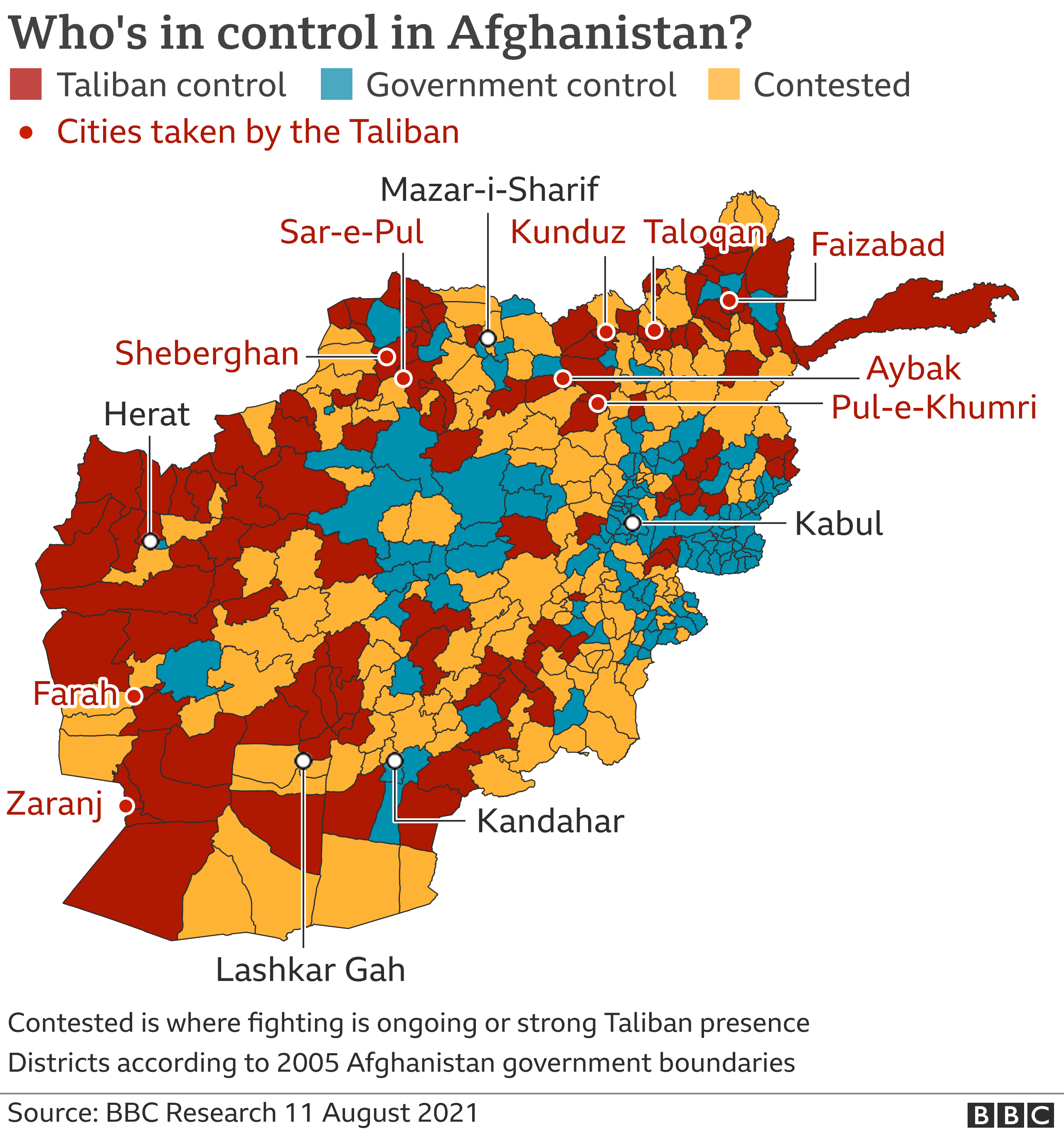

The insurgents have been capturing new territory on what seems like a daily basis as international troops have all but withdrawn. Caught in the middle is a terrified population.

Tens of thousands of ordinary Afghans have had to flee their homes - hundreds have been killed or injured in recent weeks.

I ask Ainuddin how he can justify the violence, given the pain it's inflicting on the people he claims to be fighting on behalf of?

"It's fighting, so people are dying," he replies coolly, adding that the group is trying its best "not to harm civilians".

The Taliban fighters showed off the Humvee they had captured

I point out that the Taliban are the ones who have started the fighting.

"No," he retorts. "We had a government and it was overthrown. They [the Americans] started the fighting."

Ainuddin and the rest of the Taliban feel momentum is with them, and that they are on the cusp of returning to dominance after being toppled by the US-led invasion in 2001.

"They are not giving up Western culture… so we have to kill them," he says of the "puppet government" in Kabul.

Shortly after we finish speaking we hear the sound of helicopters above us. The Humvee and the Taliban fighters quickly disperse. It's a reminder of the continuing threat the Afghan air force poses to the insurgents, and that the battle is still far from over.

We're in Balkh, a town with ancient roots, thought to be the birthplace of one of Islam's most famous mystic poets, Jalaluddin Rumi.

We passed through here earlier this year, when it was still controlled by the government, but the outlying villages were held by the Taliban. Now it's one of around 200 district centres to have been captured by the militants in this latest, unprecedented offensive.

A member of a Taliban "red unit" or special forces (kneeling, bottom left) poses with other Taliban in Balkh

One senior Taliban official said the focus in the north had been deliberate - not only because the region has traditionally seen strong anti-Taliban resistance, but also because it is more diverse.

Despite its core leadership being heavily dominated by members of the Pashtun majority, the official said the Taliban wanted to emphasise they incorporated other ethnicities too.

Haji Hekmat, a local Taliban leader and our host in Balkh, is keen to show us how daily life is still continuing.

Young schoolgirls throng the streets (though elsewhere there are reports of girls being banned from attending). The bazaar remains crowded, with both male and female shoppers.

We had been told by local sources that women were allowed to attend only with a male companion, but when we visit that does not seem to be the case. Elsewhere Taliban commanders have reportedly been far stricter.

All the women we see, however, are wearing the all-encompassing burqa, covering both their hair and face.

Haji Hekmat insists no-one is being "forced" and that the Taliban are simply "preaching" that this is how women should dress.

This young girl had her face uncovered in the bazaar - but older female shoppers wore burqas

But I've been told taxi drivers have been given instructions not to drive any woman into the town unless she's fully veiled.

The day after we leave, reports emerge of a young woman being murdered because of her clothing. Haji Hekmat, though, rejects allegations Taliban members were responsible.

Many in the bazaar express their support for the group and their gratitude towards them for improving security. But with Taliban fighters accompanying us at all times, it's difficult to know what residents really think.

The group's hardline views are at times in tune with more conservative Afghans, but the Taliban are now pushing for control of a number of larger cities.

Find out more on the Afghan conflict 2001-2021

EXPLAINER: Why is there a war in Afghanistan?

PROFILE: Who are the Taliban?

ANALYSIS: An al-Qaeda resurgence?

In the shadow of Mazar-e-Sharif's intricately tiled Blue Mosque, men and women strolled around last week in a visibly more relaxed social atmosphere.

Residents the BBC spoke to in nearby Mazar-i-Sharif were fearful of the Taliban resurgence

The government are still in control in the city and almost everyone I spoke to expressed concern about what the Taliban's resurgence will mean, particularly for the "freedoms" younger generations have grown up with.

But back in Balkh district the Taliban are formalising their own rival government. They've taken over all the official buildings in the town, bar one large, now abandoned police compound.

It used to be the headquarters of a bitter rival, the local police chief, and was partly destroyed in a suicide bombing by the militants as they fought for control of the area.

The face of the Taliban's district governor, Abdullah Manzoor, lights up with a broad grin when he talks about the operation, whilst his men chuckle. The fight here, as in so many places in Afghanistan, is deeply personal as well as ideological.

Some things haven't changed since the Taliban takeover; orange-clad street cleaners are still reporting for work, as are some bureaucrats. They're overseen by a newly appointed Taliban mayor, seated at a broad wooden desk, with a small white flag of the "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan" positioned in one corner.

The Taliban mayor in Balkh says business rates have gone down since the group took over the area

He used to be in charge of ammunition supplies, now it's taxes - and he tells me proudly the group charges business owners less than the government used to.

The transition from military to civilian life is a work in progress, though. A Taliban fighter still grasping his gun, who moves to pose behind the mayor during our interview, is ushered away by more senior figures.

In other places, however, the insurgents' hardline interpretation of Islamic scripture is more visible. At the local radio station, they used to play a mixture of Islamic music and general popular hits.

Now it's only religious chants. Haji Hekmat says they banned music promoting "vulgarity" from being played in public, but insists individuals can still listen to what they want.

I've been told, however, of a local man being caught listening to music in the bazaar. To punish him, Taliban fighters are said to have made him walk barefoot in the baking sun, until he lost consciousness.

Haji Hekmat insists no such thing happened. As we leave the station, he gestures to some of the young men working there, pointing out they don't have beards.

"See! We're not forcing anyone," he says, grinning.

It's clear the group do want to portray a softer image to the world. But in other parts of the country the Taliban are reported to be behaving much more strictly. The differences may depend on the attitudes of local commanders.

With reports of extra-judicial revenge killings and other human rights abuses in some of the areas they've captured, the Taliban have been warned by Western officials they risk turning the country into a pariah state if they try to seize it by force.

What many associate most closely with the Taliban's previous stint in power, is the brutal punishments meted out under their interpretation of Sharia law.

Last month in the southern province of Helmand, the group hanged two men accused of child kidnapping from a bridge, justifying it by saying the men had been convicted.

In Balkh, on the day we visit a Taliban court session, all the cases are related to land disputes. Whilst many fear their form of justice, for others it at least offers the possibility of a quicker resolution than the notoriously corrupt government system.

"I've had to pay so many bribes," complains one of the litigants as he discusses his previous attempts to resolve the case.

The Taliban judge, Haji Badruddin, says he's not yet ordered any corporal punishment in the four months he's been in office, and emphasises the group has a system of appeal courts to review serious verdicts.

But he defends even the harshest penalties. "In our Sharia it's clear, for those who have sex and are unmarried, whether it's a girl or a boy, the punishment is 100 lashes in public.

"But for anyone who's married, they have to be stoned to death… For those who steal: if it's proved, then his hand should be cut off."

He pushes back against criticism of the punishments as incompatible with the modern world.

"People's children are being kidnapped. Is that better? Or is it better that one person's hand is chopped off and stability is brought in the community?"

For now, despite the Taliban's rapid advance, the government remains in control of Afghanistan's biggest cities. The coming months are likely to see protracted and increasingly deadly violence as the two sides wrestle for control.

I ask Haji Hekmat if he's sure the Taliban can win militarily? "Yes," he replies. "If peace talks are not successful, we will win, God willing."

Those talks however, have stalled, and the Taliban's repeated demand for the creation of an "Islamic government" appears tantamount to a call for their opponents to surrender.

"We have defeated both the foreigners," says Haji Hekmat, "and now our internal enemies."

- Published12 August 2021

- Published30 August 2021

- Published12 August 2022

- Published16 August 2021