How China’s past shapes Xi's thinking - and his view of the world

- Published

Heightened tensions with Taiwan have focused attention on China, with many wondering where President Xi Jinping sees his country on the world stage. Perhaps the past can provide some clues, writes Rana Mitter, a history professor at Oxford University.

China is now a global power, something scarcely imaginable just a few decades ago.

Its power sometimes stems from cooperation with the wider world, such as signing up to the Paris climate agreement.

Or sometimes it means competition with it, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, a network of construction projects in more than 60 countries which has brought investment to many parts of the world deprived of western loans.

Yet there is also a highly confrontational tone to much of China's global rhetoric.

Beijing condemns the US for seeking to "contain" China through the new AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) submarine pact, warns the UK that there would be "consequences" for granting residence in Britain to Hong Kongers leaving their city because of the harsh National Security Law, and told the island of Taiwan that it should prepare to be unified with the mainland.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has asserted China's place on the global stage much more strongly than any of his predecessors since Mao Zedong, China's paramount leader during the Cold War.

Yet other elements of his rhetoric draw on sources much more longstanding - looking back to its own history, both ancient and more recent.

Here are five of these recurring themes.

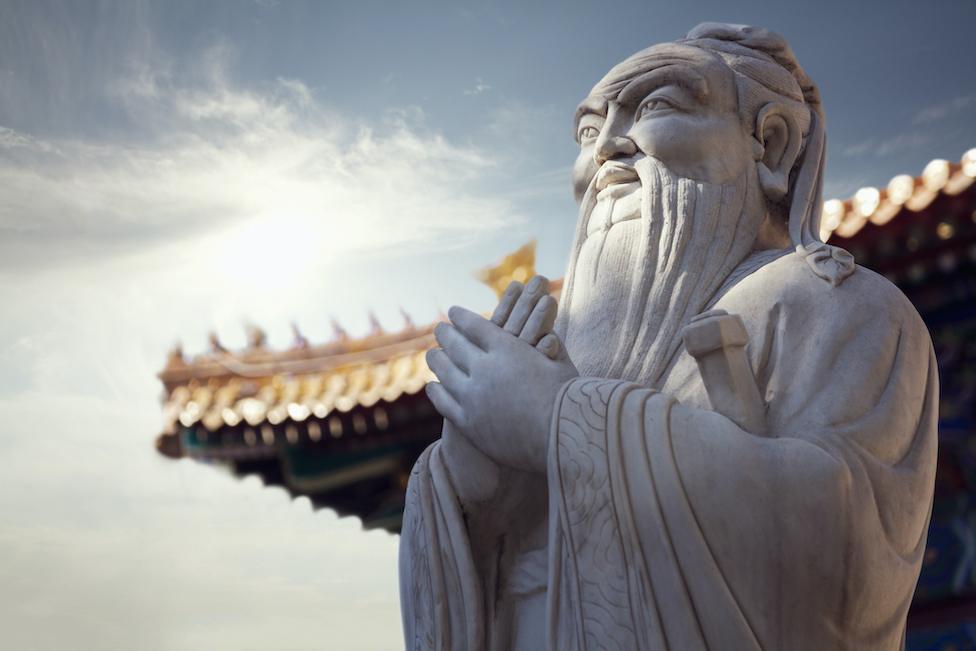

Confucian ways

For over 2,000 years the norms of Confucian thinking shaped Chinese society. The philosopher (551-479 BC) constructed an ethical system that combined hierarchy, where people would know their place in society, with benevolence, the expectation that those in superior positions would look after their inferiors.

Heavily adapted over time, this system of thinking underpinned China's dynasties until the revolution of 1911, when the overthrow of the last emperor spurred a backlash against Confucius and his legacy from radicals including the new Communist Party.

One of those communists, Mao Zedong, remained deeply hostile to traditional Chinese philosophy during his years in power (1949-1976). But by the 1980s, Confucius was back in Chinese society, praised by the Communist Party as a brilliant figure with lessons to teach contemporary China.

Today, China celebrates "harmony" (hexie) as a "socialist value," even though it has a very Confucian air. And a hot topic in Chinese international relations is the question of how that term "benevolence" (ren), another key Confucian term, might shape Beijing's relations with the outside world.

Professor Yan Xuetong of Tsinghua University has written of how China should seek "benevolent authority" rather than "dominance" in contrast with what he regards as the less benevolent role of the United States.

Even Xi Jinping's idea of a "world community of common destiny" has a traditional philosophical flavour about it - and Xi has visited Confucius's birthplace of Qufu and cited his sayings in public.

A century of humiliation

The historical confrontations of the 19th and 20th centuries still deeply shape Chinese thinking about the world.

The Opium Wars of the mid-19th Century saw western traders use force for the violent opening of China's doors. Much of the period from the 1840s to the 1940s is remembered as a "century of humiliation", a shameful era that showed China's weakness in the face of European and Japanese aggression.

During that era, China had to cede Hong Kong to Britain, territory in the north-eastern region of Manchuria to the Japanese, and a whole range of legal and commercial privileges to a range of western countries. In the post-war era, it was the USSR that tried to gain influence in China's borders, including Manchuria and Xinjiang.

This experience has created a deep suspicion toward the intentions of the outside world. Even seemingly outward-looking gestures such as China's accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 was underpinned by a cultural memory of "unfair treaties" when China's trade was controlled by foreigners - a situation which today's Communist Party has vowed never to allow again.

In March this year, an ill-tempered public session between Chinese and American negotiators in Anchorage, Alaska, saw the Chinese push back against US criticism by accusing their hosts of "condescension and hypocrisy". Xi's China does not tolerate the idea that outsiders can look down on their country with impunity.

Forgotten ally

However, even terrible events can yield more positive messages.

One such message comes from the Chinese phase of World War II, when it fought Japan essentially alone after being invaded in 1937, before the Western Allies joined the Asian war at Pearl Harbor in 1941.

During those years, China lost more than 10 million people and held back over half a million Japanese troops on the Chinese mainland, a feat commemorated widely in history books and in films and television.

The anniversary of victory against Japan is marked in Beijing

Today China portrays itself as part of the "anti-fascist alliance" alongside the US, Britain and the USSR, giving itself moral ballast by reminding the world of its role as a victor against the Axis powers.

China also draws on its historical role as a leader of the Third World in the Mao era (for instance at the Bandung Conference of 1955, and in projects such as the building of the TanZam railway in East Africa in the 1970s) to burnish its credentials as a leader today in the non-western world.

Modern history remains a key part of the way that the Chinese Communist Party perceives its own legitimacy. Yet elements of that history - notably the terrible famine caused by the disastrous economic policies of the Great Leap Forward of 1958-62 - remain almost unmentioned in China today.

And some modern wars can be used for more confrontational purposes. The last year of bumpy US-China relations has seen new films commemorating the Korean War of 1950-3 - a conflict which the Chinese remember under a different name - "the War of Resistance to America".

On your Marx

The historical trajectory of Marxism-Leninism is also deeply embedded in Chinese political thinking, and has been very actively revived under Xi Jinping.

Throughout the 20th Century, Mao Zedong and other major communist political leaders took part in theoretical debates on Marxism with immense consequences.

Chinese tourists pose for pictures in front of Mao's portrait

For instance, the notion of "class warfare" led to the killing of a million landlords in the early years of Mao's rule. Even though "class" has fallen out of favour as a way of defining society, China's political language today is still shaped by ideas of "struggle", "antagonism" and conceptions of "socialism" as opposed to "capitalism".

Major journals, such as the Party's theoretical organ Qiushi, regularly debate the "contradictions" in Chinese society in terms that draw extensively from Marxist theory.

Xi's China defines the US-China competition as a struggle that can be understood in terms of Marxist antagonism.

The same is true for the economic forces in society, and their interaction - the difficulties in growing the economy and keeping that growth suitably green are interpreted in terms of contradiction. In classic Marxism, you reach an agreed point, or synthesis - but not before you work through often painful and lengthy "antagonisms".

Taiwan

Beijing stresses the unshakable destiny of the island of Taiwan, which it defines as unification with mainland China.

Yet the past century of Taiwan's history shows that the issue of its status waxes and wanes in Chinese politics. In 1895, after a disastrous war with Japan, China was forced to hand over Taiwan, which then became a Japanese colony for the next half century.

China's southeastern coast can be seen from the Taiwanese island of Kinmen

It was then briefly unified with the mainland by the Nationalists from 1945 to 1949. Under Mao, China missed its chance to unify the island; the American Truman administration would have probably let Mao take it, until the People's Republic of China joined the North Koreans in invading South Korea in 1950, prompting the Korean War and suddenly turning Taiwan into a key Cold War ally.

Mao launched attacks on the Taiwan coast in 1958, but then ignored the territory for the 20 years after that. After the US and China re-established relations in 1979, there was an uneasy agreement that all sides would agree that there was One China, but not agree over whether the Beijing or Taiwan regime was actually the legitimate republic.

Forty years on, Xi Jinping is insistent that unification must come soon, while the aggressive rhetoric and fate of Hong Kong has led Taiwan's public, now citizens of a liberal democracy, to become increasingly hostile to a closer relationship with the mainland.

Professor Rana Mitter teaches at Oxford University where he specialises in the history and politics of modern China. His latest book is China's Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism