Mount Everest: Even world's highest peak not immune to the Ukraine war

- Published

Ang Sarki Sherpa has one of the most dangerous jobs in the world, but he takes the risks in his stride.

Mr Sherpa is one of Nepal's highly experienced mountain guides, known as "icefall doctors", who fix ropes and aluminium ladders for climbers on Mount Everest, the world's tallest mountain.

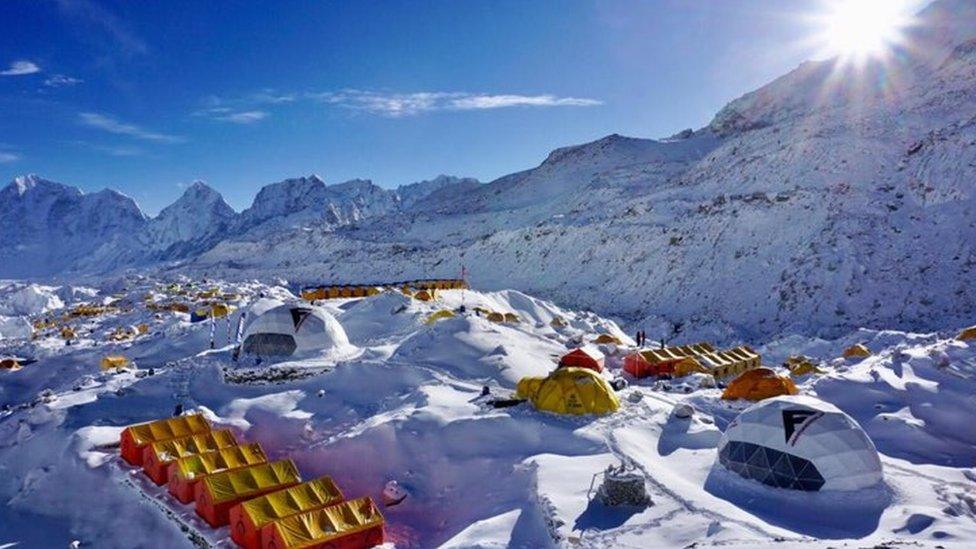

The work by the sherpas, who must negotiate crevasses and constantly shifting glacier ice, enables hundreds of mountaineers to attempt Everest from the Nepalese side every year. They start from base camp, where they converge in April and May.

Recent years have been blighted by disaster - deadly avalanches on Everest in back-to-back years were followed in 2020 by Covid, which kept climbers away. Now war in Ukraine is denting hopes that visitor numbers will return to pre-pandemic levels.

Standing outside his yellow tent at the top of the sprawling base camp, the 50-year-old Mr Sherpa pointed to the vast Khumbu icefall towering above.

The Khumbu icefall, pictured last year, offers an early challenge to teams scaling Everest

"That is one of the danger zones. Lots of crevasses between the snow there. If you are not careful, you might fall into them. Even if you make a trail with ropes it may disappear after a month. It's a risky job," he tells the BBC.

Mr Sherpa leads a six-member team of local guides, who were acclimatising when the BBC visited. Ropes and ladders were strewn around their tents as they drank tea.

Around them base camp was bustling with activity. Advanced teams of various expeditions were setting up tents and organising supplies as the spring season got under way.

The "icefall doctors" identify the safest route and fix ropes up to Camp One and Two. Another team undertakes the work further above and all the way to the summit.

It's the busiest time of the year for Ang Sarki Sherpa and his team

Mr Sherpa and his colleagues are only too aware of the dangers involved.

An avalanche above the Khumbu icefall killed 16 sherpas while they were fixing ropes in 2014. A year later, 19 people were killed in an avalanche triggered by a massive earthquake which devastated swathes of Nepal.

Mountaineering in the Everest region has been hit hard by the pandemic. This season the sherpas were looking for things to pick up - then Russia invaded Ukraine.

"Because of that war we hear that a number of teams from that region have cancelled their plans. So, we may not have that many expeditions this year," Mr Sherpa tells me.

The "icefall doctors" fix ropes and ladders for the expeditions attempting to climb Everest

Base camp is not just for those hoping to reach the 8,848m Everest summit.

The hike to the camp, nearly 5,400m above sea level, attracts tens of thousands of people from around the world each year.

It can take up to two weeks to complete the trek starting from the town of Lukla, the gateway to the Everest region.

After Covid struck in 2020, Nepal allowed mountaineers on Everest in 2021 and issued 408 permits to summit. This year, the Nepal tourism ministry had issued only 287 climbing permits by 19 April.

"The war has affected mountaineers coming from Russia and Ukraine this year. We have only one Ukrainian climber for Everest so far," says Surya Prasad Upadhyay, the director of the mountaineering division at the country's tourism department.

Seventeen Russians have been issued Everest climbing permits - others have cancelled. Russians have been affected by a collapse in the value of their currency, the rouble, and difficulties accessing currency abroad after international sanctions targeted their economy following the invasion.

Supplies to last the season are piled around the sherpas' tents

Small villages all the way up to base camp are a lifeline for thousands of trekkers and mountaineers. Here again, the war in Ukraine has had an impact.

"Fuel and prices went up after the war started. For us they are important to run our business. We hear that the prices might go up further. That's worrying," says Ang Dawa Sherpa, who runs the Sherpa Village guest house in the village of Phakding.

Nepal's government has increased petrol and diesel prices four times this year so far, making it costlier to bring in supplies.

With more and more people wanting to climb Everest in recent years, questions have been asked over whether the climbing routes have become too crowded.

A shocking image of hundreds of people waiting in line, external, practically cheek by jowl, along the snow-covered route in 2019 raised serious questions about safety.

The government says it has taken steps to mitigate the situation.

"We are working to address the crowd problem on Everest. Our ministry is working to give longer permits to the mountaineers so that it can help to regulate the expeditions," says Maheshwor Neupane, secretary in the ministry of tourism in Kathmandu.

Discarded equipment and rubbish was left scattered around Camp 4 in 2018

Mr Neupane says a five-member team of officials will be deployed at base camp throughout the climbing season to monitor expedition groups.

Rubbish left behind by the crowds is also a growing problem.

"It is a cause of concern for us. Up on Everest and other mountains the leftover trash, dead bodies and other waste items are still there," Bhumiraj Upadhyaya, chief warden of the Sagarmatha National Park, tells the BBC.

"The Nepali army is now involved in clearing them but it's a difficult process."

At base camp, Ang Sarki Sherpa and his team mates discuss their next day's climb.

They know that mountains like Everest are hugely risky places to work - but they also offer a livelihood for people like them and tens of thousands of others in the region.

Additional reporting by Surendra Phuyal in Nepal

- Published29 March 2022

- Published23 February 2024

- Published5 May 2021

- Published18 April 2014