The extraordinary process of secretly interviewing people inside North Korea

- Published

In the dead of the night, two North Koreans meet in secret. One is an ordinary North Korean citizen who has agreed to risk all to be interviewed by the BBC. The other is a source, working for an organisation in South Korea to leak information out of the country.

At a secure location that cannot be bugged, the source relays one of our questions to the citizen and notes down the answer. Later, when it is safe, they will send it back to us, in multiple instalments. Sending even one full answer at a time is too risky.

This is the start of a painstaking process that will take us many months, as we investigate the consequences of the North Korean government's decision to seal the country's border more than three years ago.

North Koreans are forbidden from talking to anyone outside the country, especially journalists, and if the government finds out they have done so, they could be killed.

But when the border was shut in January 2020, in response to the coronavirus pandemic, a country that was already difficult to report on became virtually impenetrable.

All the sources that journalists would ordinarily rely on to relay what was happening on the ground dried up, as foreign diplomats and aid workers left the country. It also became nearly impossible for North Koreans to escape and share their experiences.

At the same time, there was good reason to suspect the border closure was causing people significant suffering, based on our knowledge of how people in North Korea make their living and acquire their food. Then, last year, we started to get unconfirmed reports of severe food shortages and possible starvation.

This is why we decided to take such extraordinary measures, to interview three ordinary North Koreans inside the country.

First, we sought advice from those who work closely with North Koreans and understand the risks. Sokeel Park, from the organisation Liberty in North Korea, who has been working with escapees for more than a decade, was of the view this was an important and worthwhile undertaking, in spite of the risks.

"There is not a single North Korean who won't understand the danger, and if people want to do this, I think we should respect that," he told us. "Every conversation with people inside North Korea, every titbit of information, is so valuable, because we know so little," he said.

But to do this, we could not work alone. We teamed up with a news organisation in South Korea, Daily NK, that has a network of sources inside the country. These sources found us people who wanted to be interviewed. Aware we would only be getting a snapshot of life inside the country, we chose to speak to people of varying ages from different areas.

We explained what the BBC was, and how far and wide their interviews would be seen and heard, and they gave their consent.

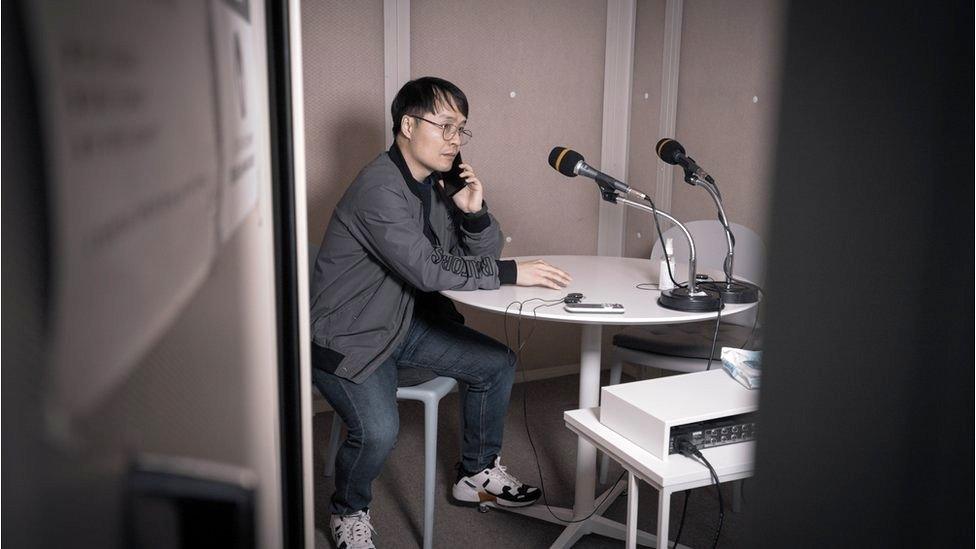

"They are looking forward to telling the world how bad the situation is in North Korea," said Daily NK's editor-in-chief Lee Sang-yong. "They hope the international community will take notice."

Mr Lee has been working with his sources for 13 years to smuggle information out of North Korea. He assured us that his methods of communication were robust. He was confident he could keep people safe but warned that the process would take time.

Lee Sang-yong, editor-in-chief of Daily NK - the organisation that helped us carry out the interviews

As we waited, there were moments we worried we might not get enough information. What if we received one-line answers - perhaps not even enough to report? This was the gamble.

But when we finally collated the messages, we were blown away by the level of detail. People revealed far more than we had expected, and the situation was worse than we had imagined. It pointed to a dire humanitarian and human rights situation unfolding in the country, and chronic food shortages.

Inside North Korea - voices from behind the sealed border

We then set about verifying as much as we could. Helpfully, our three interviewees corroborated each other. They all cited the same quarantine rules and the same new laws which frightened them. They all spoke about the scarcity of food and medicine, and had experienced increasingly severe crackdowns and punishments. They even shared many of the same hopes and fears.

But there were also illuminating differences. It appeared there was more government support in the capital Pyongyang than in the border towns, but also more control, surveillance and fear there - which was in line with what we had expected.

Our next step was to take our interviews to NK Pro, a news service in Seoul which monitors North Korea. One of the only remaining sources of information on North Korea is the country's own state-run newspaper and TV channel. While much of the content is propaganda, NK Pro's state media expert Chung Seung-yeon monitors this daily, combing it for clues as to what is really happening in the country.

"We think of North Korea as a very secret state. Certainly, they never speak loudly about their problems, but they drop hints," she said. And when they actually mention a problem, as they have done with the food crisis, this means it's "a really big deal", she explained.

She showed us one news report from February in which North Korean party members were praised for donating rice to the government. "That the state is receiving grain from its people, shows us how desperate the food situation is," she pointed out.

Expert on North Korean state media, Chung Seung-yeon, looks for clues in their reports about what is really happening

With Ms Chung's help we were also able to confirm many of the quarantine and lockdown rules our interviewees had cited, and the new laws and punishments that had been introduced.

To corroborate other details, we analysed the available data on food prices and trade, and viewed satellite images of the border. We combed the texts of new laws that had been smuggled out the country, while cross-referencing our interviews with reports from the South Korean government, the UN, and other sources, until we were confident that our interviews - while not comprehensive - provided reliable snapshots of life in North Korea.

As much as we have published, there are many details we have held back, to protect our interviewees. But through their bravery, we know so much more about the situation in North Korea than we did before.

"The world has not realised how bad things are for the North Korean people right now," said Sokeel Park. "These interviewees are not the full picture. In future years, we'll probably learn in depth just how difficult this period has been," he said.

When we last checked in with our interviewees, through Daily NK, they were all safe.

Related topics

- Published14 June 2023