What is Hong Kong's political controversy about?

- Published

The interpretation of the Basic Law means that the two pro-independence lawmakers will be barred from office

The Chinese government has made an unprecedented intervention in Hong Kong politics, issuing a ruling that effectively means two elected lawmakers will not be allowed to take their seats.

How did Hong Kong get to this point?

It starts with the Basic Law

The Basic Law has been the mini constitution of Hong Kong since it was handed back to China in 1997.

It enshrines the "one country, two systems" principle, and has been considered a promise from Beijing to the people of Hong Kong that they would be allowed to keep their way of life for the following 50 years.

Under Basic Law, Hong Kong handles most of its affairs internally, while Beijing is responsible for defence and foreign affairs.

However, the law also stipulates that the National People's Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) - China's rubber-stamp parliament - holds the ultimate "power of interpretation" of the law.

So why is it an issue now?

Article 104 states that all elected Hong Kong officials and judges need to "swear to uphold" the Basic Law and "swear allegiance to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China".

Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying and Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen filed a judicial review regarding the disqualification of the two lawmakers

But two recently elected pro-independence lawmakers have repeatedly refused to say the oath properly.

Sixtus Leung and Yau Wai-ching shouted a derogatory term for China and showed a "Hong Kong is not China" flag during their oath-taking ceremony, causing chaos in the Legislative Council.

Article 104 does not mention any consequences if officials fail to be sworn in properly, nor whether they would be able to retake the oath, so the outcome of their provocative stance was unclear.

Before waiting for the results of a judicial review within Hong Kong, Beijing intervened to issue its own interpretation of the law.

Why is Beijing's interpretation so controversial?

The NPCSC ruled that officials must "accurately, completely and solemnly" read out the portion of the oath that swears allegiance to Beijing.

It also states that officials will bear legal responsibilities if they later commit any doings that "defy the oath" - another term that is not included in Article 104.

This means Leung and Yau cannot take their seats despite being elected.

But critics say what Beijing has done is effectively change the law, rather than just clarify how it should be enacted.

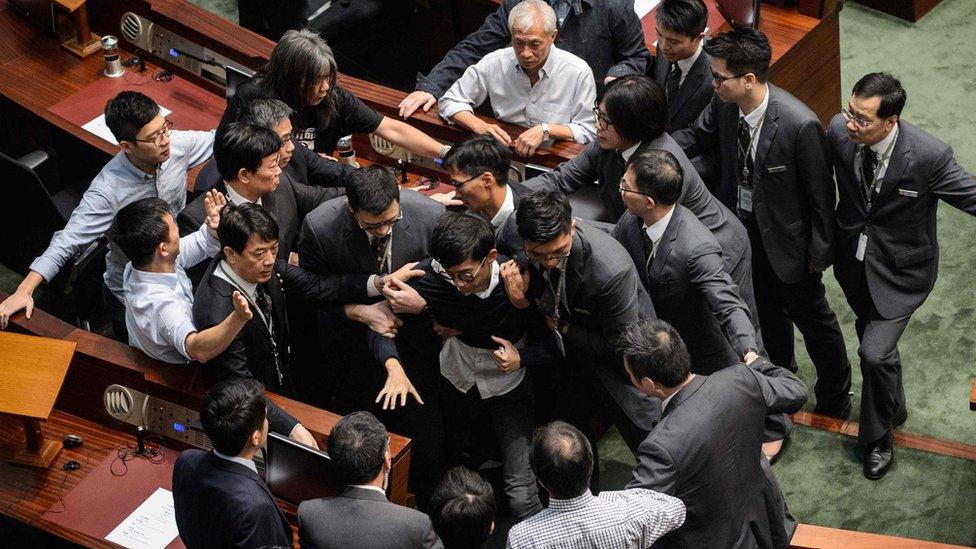

Scuffles broke out during a protest against the interpretation of the Basic Law by the National People's Congress Standing Committee the night before the formal announcement

They argue that, in theory, the Chinese government will now be able to stop any democratically elected lawmakers it doesn't like from taking office.

On top of that, the judicial review is still in process, some believe Beijing has undermined the city's judicial independence, and there are fears it could go on to change other articles of the Basic Law.

China says the move was "absolutely necessary", and "complies with the common aspiration of the entire Chinese people" including those in Hong Kong.

Has Beijing done this before?

This is the furthest reach of Beijing into Hong Kong politics since the handover, but it is the fifth time it has acted to interpret the Basic Law.

In 1999 it ruled that mainland-born children of Hong Kong citizens were not residents of Hong Kong, overturning the Court of Final Appeal ruling.

In 2004 the Standing Committee was given first say over any political reforms involving the election of the chief executive and the LegCo members.

In 2005, it decided on the length of the term of the chief executive who ran for a by-election.

In 2011, Hong Kong's Court of Final Appeal asked Beijing to clarify whether Congo enjoyed absolute diplomatic immunity in the city, where it was being sued by a US firm.

Reporting by the BBC's Grace Tsoi

- Published7 November 2016

- Published7 November 2016

- Published2 November 2016