Cantonese v Mandarin: When Hong Kong languages get political

- Published

For some young people in Hong Kong, speaking Mandarin is somewhat taboo

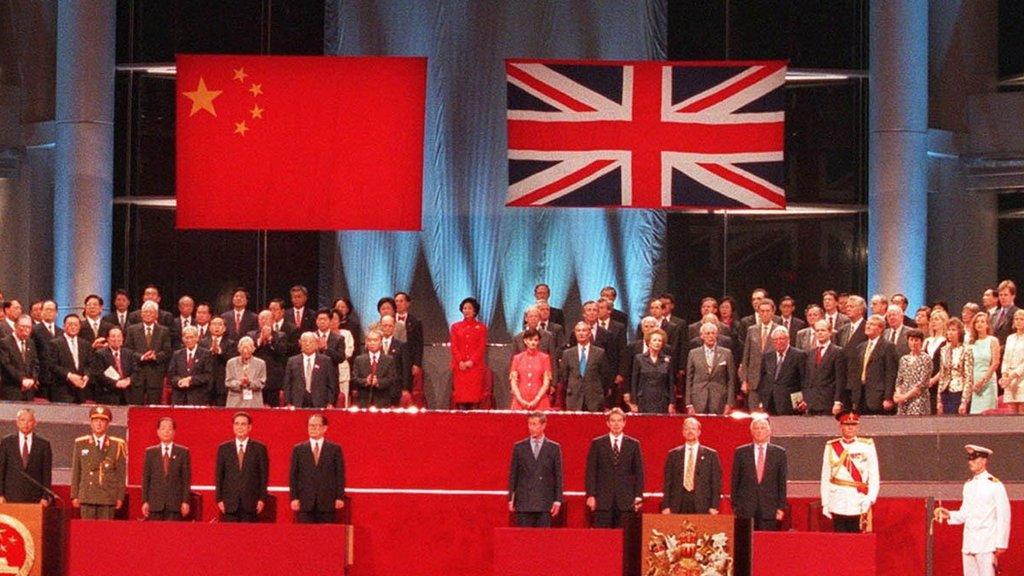

When Hong Kong was handed back from the UK to China in 1997, only a quarter of the population spoke any Mandarin.

Now, two decades later, that figure has nearly doubled.

But even as people get better at communicating in Mandarin, also known as Putonghua, some in Hong Kong are losing interest, or even downright refusing to speak it.

Chan Shui-duen, a professor of Chinese and Bilingual Studies at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, said that among some of her students, speaking Putonghua can almost be taboo.

"Especially among young people, the overall standard of Putonghua is rising," she said. "But some of them just reject it."

This is because, for many, Putonghua has become an unwelcome reminder of the increasing "mainlandisation" of Hong Kong.

Read more about Hong Kong since the handover:

The social rejection of Putonghua has come as people question their Chinese identity, which has alarmed both the Hong Kong and mainland Chinese governments.

Last June, an annual poll by the University of Hong Kong found that only 31% of people said they felt proud to be Chinese nationals, a significant drop from the year before, and a record low since the survey first began in 1997.

Language of success

Cantonese v Mandarin: What's the difference?

Even as resentment against Putonghua builds, there is grudging awareness that - with nearly one billion speakers in the world - fluency in the language may hold the key to wealth and success in Hong Kong.

When my eldest child turned two, I started looking for a suitable kindergarten.

It surprised me that the most sought-after schools in Hong Kong taught in English or Mandarin, rather than Cantonese, which is the default language for nearly the entire population.

And I was shocked to hear from Ruth Benny, founder of the Hong Kong-based education consultancy Top Schools, that 99% of her clients, both local and expatriate, strongly preferred Mandarin.

"I believe Cantonese is not valued in the context of formal education much at all," said Ruth Benny, the Hong Kong-based founder of Top Schools.

She said Cantonese families are happy for their children to be "socially fluent," but preferred them to learn Chinese literacy in Mandarin, with a standard form of written Chinese.

The rising educational preference for Mandarin at the expense of Cantonese is causing anger and anxiety among Hong Kong residents, 20 years after the city was handed back from the UK to China.

They worry the city's distinctive culture and identity will eventually be subsumed by mainland China, with some questioning if the language - and the city so closely identified with it - is dying.

Language battle

Before the 1997 handover, most local schools in Hong Kong officially used English as the medium of instruction, but in practice also taught in Cantonese.

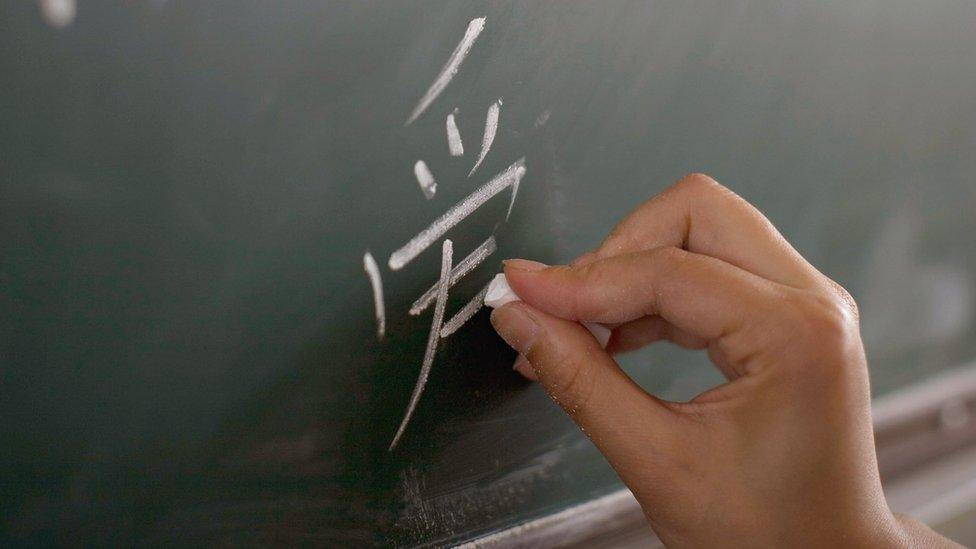

Mandarin, also known as Putonghua, is seen as the key to success by many Hong Kong parents

Mandarin, also known as Putonghua, was introduced in schools in the 1980s and only became a core part of the curriculum in 1998.

Cantonese and Mandarin: which came first?

A man at a protest expressing support for Cantonese

Cantonese is believed to have originated after the fall of the Han Dynasty in 220AD, when long periods of war caused northern Chinese to flee south, taking their ancient language with them.

Mandarin was documented much later in the Yuan Dynasty in 14th century China. It was later popularised across China by the Communist Party after taking power in 1949.

"As expected, after the handover, Putonghua became more privileged and popular," said Brian Tse, a professor of education at the University of Hong Kong.

By 1999, the Education Bureau had started publicising its long-term goal of adopting Putonghua, not Cantonese, as the medium of instruction in Chinese classes, even though it offered no timetable on when this should be achieved.

About a decade later, the Standing Committee on Language Education and Research (Scolar), a government advisory group, announced plans to give $26m to schools to switch to Putonghua for Chinese teaching.

It said a maximum of 160 schools could join the scheme over four years.

Cantonese concern groups estimate that 70% of all primary schools and 25% of secondary schools now use Putonghua to teach Chinese.

Government bias?

Officially, the city government encourages students to become bi-literate in Chinese and English and trilingual in English, Cantonese and Mandarin.

But Robert Bauer, a Cantonese expert who teaches at several universities in Hong Kong, said Scolar and the Education Bureau were essentially "bribing" schools to make the switch from Cantonese to Mandarin as the medium of instruction in Chinese language classes.

"They're taking orders from the people of Beijing," he said. "Cantonese sets Hong Kong apart from the mainland. The Chinese government hates that, and so does the Hong Kong government."

It is now 20 years since the UK handed control of Hong Kong back to China

Those who support this view point to a gaffe made by the Education Bureau in 2014.

On its site detailing Hong Kong's language policy, it stated that Cantonese was a "Chinese dialect that is not an official language".

It caused an outcry, as Hong Kong residents certainly believe theirs is a proper form of Chinese, and not just a dialect. The bureau was forced to apologise and delete the phrase.

In 1997, there was hope and expectation that the city, unlike the rest of China, would soon enjoy universal suffrage.

But the Chinese government's interpretation of reform angered the public.

Tens of thousands of people took to the streets in unprecedented protests in 2014.

The reform proposal was vetoed by pro-democracy politicians in 2015, and today, Hong Kong seems stuck in a political stalemate.

Against this backdrop, Cantonese has not just survived but thrived in a totally unexpected way, according to linguistics expert Lau Chaak-ming.

Starting about 10 years ago, writing in vernacular Cantonese, in addition to standard Chinese, began appearing in public in advertisements.

Mr Lau said this trend has greatly accelerated in the past four years.

"We can now use our language in the written form," he told me proudly.

Previously, advertisements and newspapers used only standard written Chinese, which is easily comprehensible to all Chinese-literate readers, whereas non-Cantonese speakers might struggle to understand the written vernacular.

Mr Lau dates the rise in written Cantonese to greater awareness of a local Cantonese identity, as opposed to a more general Chinese sense of self.

Mr Lau and a number of volunteers are compiling an online Cantonese dictionary, documenting its evolution.

Working in parallel, Mr Bauer, the Cantonese expert, will soon be publishing a Cantonese-English dictionary, which will be available online and in book form.

Dying language?

According to these experts, Cantonese isn't dying at all. For now.

"From a linguistic point of view, it's not endangered at all. It's doing quite well compared to other languages in the China region," said Mr Lau.

But he and others worry about the long-term consequences of the rise of Putonghua in Hong Kong, especially as more schools seem to be keen to teach in the medium.

"Speaking, and writing, Cantonese has now become an political act," said Robert Bauer. "If present trends continue, children are not going to speak Cantonese down the road. It will become endangered."

An advert promoting a Cantonese Opera house in Hong Kong

He cited the history of Cantonese in Guangdong province, where he believes efforts to spread Putonghua have been too successful, with children now not using their mother tongue.

But Ms Chan of Hong Kong Polytechnic is less pessimistic.

Contrary to what had been predicted, she says, Cantonese has maintained, and even extended, its dominant position after the handover in the areas of politics and law.

It has been "transmuted", she maintains, from a low-status dialect to a high-status form that displays all the full functions of a standard language - which is something quite unique and unprecedented in the Chinese context.

Cantonese may not entirely enjoy the "prestige" of a national language, but it is quite important - and indispensible for anyone living and working in Hong Kong.

- Published3 April 2017

- Published19 January 2017

- Published29 April 2017

- Published27 November 2015

- Published3 May 2015

- Published14 December 2016