Xi Jinping: How China's president got ahead, in hats

- Published

Liao Ailian and Pan Guixian are among 3000 delegates from across China

As China's most significant political gathering in decades draws to a close, Liao Ailian and Pan Guixian are preparing to head home.

They're among the almost 3,000 delegates from across China who have spent the past two weeks sitting in the Great Hall of the People, voting on the decisions mostly already taken by the Communist Party leadership behind closed doors.

Like many of the delegates, the two women have their own political interests.

If they're at all concerned about their influence - in a system that pretty much guarantees a lack of it - they don't show it.

Ms Liao says she's interested in rural road construction, and Ms Pan, rural women's issues.

Their traditional hats are meant to mimic the shape of the tail of a phoenix, but along with the other ethnic costumes on display, they help give the impression of something else too.

They lend the event the appearance of the ethnic equality that's meant to be guaranteed by the constitution.

In reality, power in China is becoming ever more centralised towards the Han ethnic majority, towards Beijing and, most importantly, towards the ruling elite at the top of the Communist Party.

And now, following the vote to remove the presidential term limits - the act for which this parliament will long be remembered - power has been concentrated further, into the hands of just one man.

It represents a seismic political upheaval - so significant in fact that some analysts refused to believe even recently that such a move was possible. They are, one presumes, now eating their own hats.

Let's hope they're not wearing one of these.

Zhaxi Jiancun in his hat made of fox hair

Zhaxi Jiancun, with his traditional Tibetan fox fur hat, is preparing to make one of the longest journeys home from Beijing.

His main political interest, he says, is in promoting Tibet's infrastructure development.

And that puts him right on message with the central theme of this parliament - national rejuvenation.

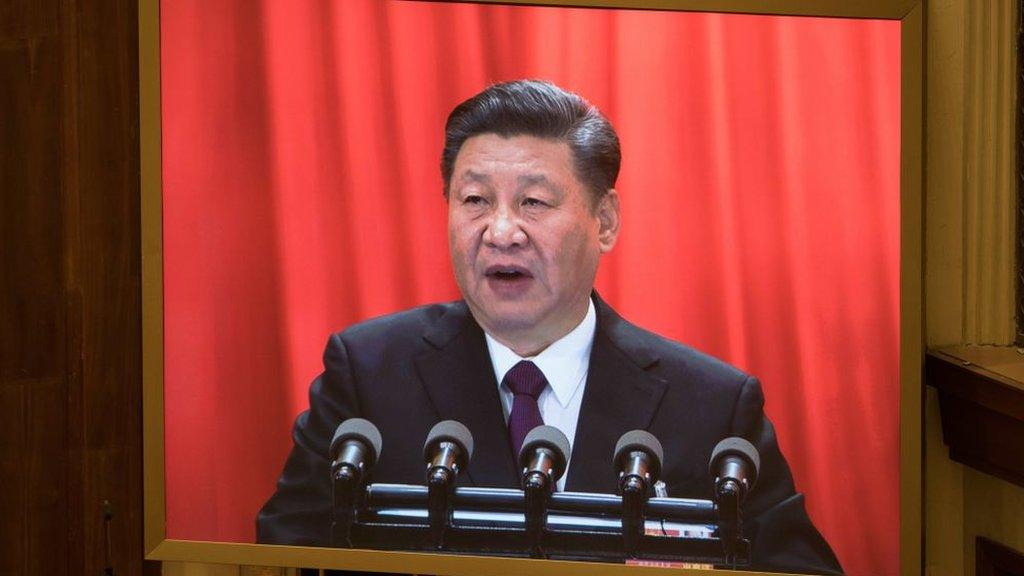

Xi Jinping's closing address to parliament gave the clearest sense yet that he believes that China's long awaited destiny is within reach.

It was an overtly nationalist speech; full of praise for Chinese ingenuity and invention and coupled with stern warnings about the need to protect territorial integrity in areas like Tibet.

He offered a vision of a future not merely of improved livelihoods and economic growth, but of something far more historic - of China retaking its rightful place on the global stage as a powerful country.

Other members of the Chinese elite, the media and the political establishment, sense it too - a feeling that with Western democracies facing crisis and a decline in influence, China's moment has come.

Might that be why the parliament has been so ready to hand Mr Xi unlimited, indefinite power?

The president urged lawmakers to rule in the interest of the people

Wang Xiangwei is a former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post and one of those who believes the president needs more than two terms to accomplish his mission.

"I think there is a strong compelling argument that because he has brought China into the leading ranks of the world and restored its rightful place on the world stage, that's why he has received so much support within the leadership and outside the party to get a stronger mandate," he tells me.

"Of course there are concerns but I think the Chinese government has done a pretty good job of making sure they're not showing in public."

That's an understatement.

There has been barely a murmur of dissent at the parliament - just two votes against the abolition of the term limits - and very heavy handed censorship of almost all public discussion.

Su Qiong says her main interest is migrant worker issues

Su Qiong is from China's Tujia ethnic group in eastern Fujian province, and says her main interests are migrant worker issues.

Interestingly, China has experimented with giving its vast army of internal migrant labourers a voice at its parliamentary gatherings. But representation has been extremely low and the possibility of enacting political change from below, extremely remote.

And therein lies the danger.

One party rule was, arguably, much easier in the good old days of double-digit annual economic growth.

More on China under Xi

A decade or so ago, the supposed grand bargain between the party and the people seemed to make some kind of sense; we'll do the politics, you get rich.

But today's story is far more complex; it is one of slowing economic growth, industrial overcapacity, an ageing workforce and major environmental pollution, to name just a few of the challenges.

The solutions will require a careful balancing of interests - unemployed migrant workers against factory bosses, people's health against economic growth, state-owned industries against private enterprise.

There was once a time when even some party insiders used to argue that the process of deciding fairly who should be winners and losers would require at least limited political reform.

Not anymore.

One of the hallmarks of President Xi's first term has been the stifling of anyone making those arguments - hundreds of activists, democracy campaigners and lawyers have been detained, jailed or otherwise silenced.

And now the two-term limit, introduced after the death of Chairman Mao - precisely to prevent a return to the terror and tyranny of his indefinite rule - is gone too.

Might President Xi, in the middle of some future economic crisis, surrounded only by yes-men, begin to make serious mistakes of his own?

Qi Batu is interested in poverty relief

Qi Batu, sporting his trilby-style wool hat, is from Inner Mongolia. His political interest is poverty relief.

Among all the talk about historic destiny in President Xi's speech, the subject of poverty got barely a mention, but it is one dear to his heart.

Alongside President Xi's anti-corruption campaign - used to great effect to silence his political rivals - the anti-poverty campaign has been another defining feature of his first term.

State TV has been full of images of Mr Xi sitting in humble village homes, listening earnestly and dispensing wisdom.

The feedback loops are clearly limited in a country with such a large democratic deficit as China, but that doesn't mean the government can ignore the people entirely.

In the absence of voting, the Communist Party has a long history of using opinion polls to at least try to find out what the people are really thinking.

And here perhaps, lies a glimmer of hope for China as it appears to take a risky step backwards in time to the era one-man-rule.

Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese Studies and Director of the Lau China Institute at King's College, London, points out the China of President Xi is a very different place from that of Chairman Mao.

Should China's Xi be president for life?

"So it looks worrying that there's this sort of incredibly powerful leader," he tells me.

"The fact is that he will have to keep a very pushy expectant middle-class happy. They are not the sort of people that will be loyal to the party if they don't get the things that the expect in their lives - he is their servant in the end."

There are plenty of people who, for now, buy Mr Xi's vision of national rejuvenation, and are willing to back him as the man to deliver it.

As the saying goes; if the cap fits, wear it.

And so, it seems only appropriate to end on one:

Min Xiaoqing, a Russian ethnic delegate from Xinjiang, wearing a kokoshnik

- Published20 March 2018

- Published20 March 2018

- Published13 October 2017

- Published13 March 2018

- Published19 March 2018

- Published20 March 2018

- Published13 March 2018