Hong Kong-China extradition plans explained

- Published

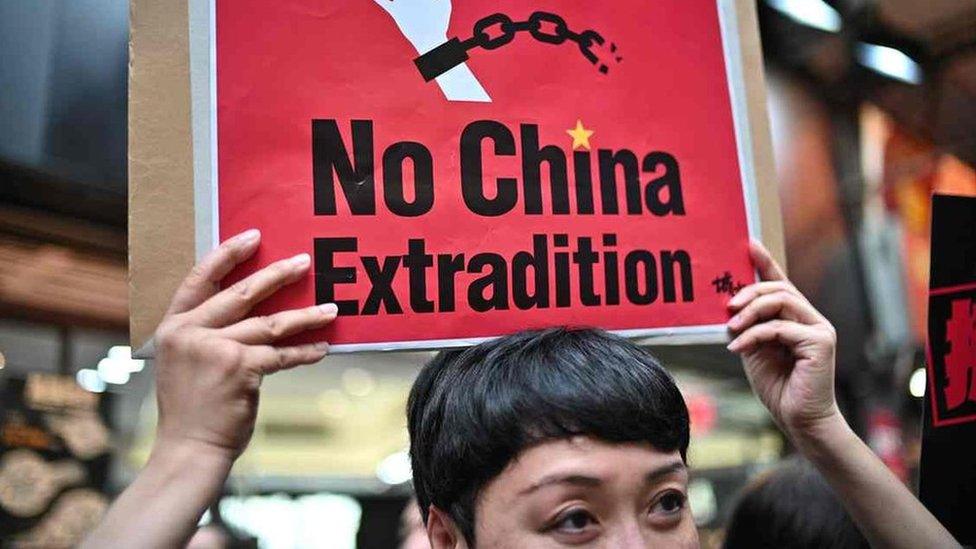

Critics fear the proposed amendments will expose anyone in Hong Kong to China's flawed justice system

Hong Kong has seen months of protests sparked by a highly controversial plan to allow extraditions to mainland China.

The government had argued the proposed amendments would "plug the loopholes" so that the city would not be a safe haven for criminals.

But critics said those in the former British colony would be exposed to China's deeply flawed justice system, and it would lead to further erosion of the city's judicial independence.

After months of protests which often developed into violence, the bill was officially withdrawn, but that has failed to stop the unrest.

What were the proposals?

The existing extradition law specifically states that it does not apply to "the Central People's Government or the government of any other part of the People's Republic of China".

But the proposed changes would have allowed for the Hong Kong government to consider requests from any country for extradition of criminal suspects, even countries with which it doesn't have an extradition treaty and including mainland China, Taiwan and Macau.

So people wanted for crimes in those territories could potentially be sent there to face trial.

The requests would be decided on a case-by-case basis by the chief executive.

Hong Kong is part of China but has its own judicial system

Several commercial offences, such as tax evasion, were removed from the list of extraditable offences amid concerns from the business community.

Hong Kong officials always said Hong Kong courts would have the final say whether to grant such extradition requests, and suspects accused of political and religious crimes would not be extradited.

The government sought to reassure the public with some concessions, including promising to only hand over fugitives for offences carrying maximum sentences of at least seven years.

Why the change now?

The proposal came after a 19-year-old Hong Kong man allegedly murdered his 20-year-old pregnant girlfriend while holidaying in Taiwan together in February 2018. The man fled Taiwan and returned to Hong Kong last year.

Taiwanese officials sought help from Hong Kong authorities to extradite the man, but Hong Kong officials said they could not comply because of a lack of extradition agreement with Taiwan.

But the Taiwanese government has said it would not seek to extradite the murder suspect under the proposed changes, and urged Hong Kong to handle the case separately.

Why is this controversial?

Critics said people would be subject to arbitrary detention, unfair trial and torture under China's judicial system.

"The proposed changes to the extradition laws will put anyone in Hong Kong doing work related to the mainland at risk," said Human Rights Watch's Sophie Richardson in a statement earlier this year.

"No one will be safe, including activists, human rights lawyers, journalists, and social workers."

Lam Wing Kee, a Hong Kong bookseller, said he was abducted, detained and charged with "operating a bookstore illegally" in China in 2015 for selling books critical of Chinese leaders.

In late April, Mr Lam fled Hong Kong and moved to Taiwan where he was granted a temporary residency visa.

"If I don't go, I will be extradited," Mr Lam said during a recent protest against the bill. "I don't trust the government to guarantee my safety, or the safety of any Hong Kong resident."

Scuffles broke out among Hong Kong lawmakers during deliberation of the controversial amendment

Who opposed the proposal?

Opposition to the law was widespread from the start, with groups from all sections of society - ranging from lawyers to housewives - voicing their criticism or starting petitions.

Hundreds of petitions against the amendments started by university and secondary school alumni, overseas students and church groups also appeared online.

Lawyers, prosecutors, law students and academics marched in silence and called on the government to shelve the proposal.

Hundreds of thousands of people have taken to the streets for many weekends in a row in some of the largest demonstration since the territory was handed over to China by the British in 1997.

Several countries also expressed concern.

A US congressional commission said in May it risked making Hong Kong more susceptible to China's "political coercion" and further erode Hong Kong's autonomy.

Britain and Canada said they were concerned over the "potential effect" that the proposed changes would have on UK and Canadian citizens in Hong Kong.

The European Union also issued a diplomatic note to Mrs Lam expressing concerns over the proposed changes to the law.

China's foreign ministry has refuted such views, calling them attempts to "politicise" the Hong Kong government proposal and interference in China's internal affairs.

Summary of the protests in 300 words

All the context you need on the protests

Timeline of events so far

The background to the protests in video

More on Hong Kong's history

Profile of Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam

Has the bill now been scrapped?

Carrie Lam indefinitely delayed the bill in mid-June, but that was followed by one of the largest protests, as opponents demanded it be revoked entirely.

Ms Lam later reiterated that the bill was "dead" and would expire when the Legislative Council's term ended next year. But that failed to stop or slow the protests.

In October, when LegCo convened after the summer break, it formally scrapped the law.

But by that point, protests were entrenched and had developed into wider anger against the government and over allegations of police brutality.

Isn't Hong Kong part of China anyway?

A former British colony, Hong Kong is semi-autonomous under the principle of "one country, two systems" after it returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

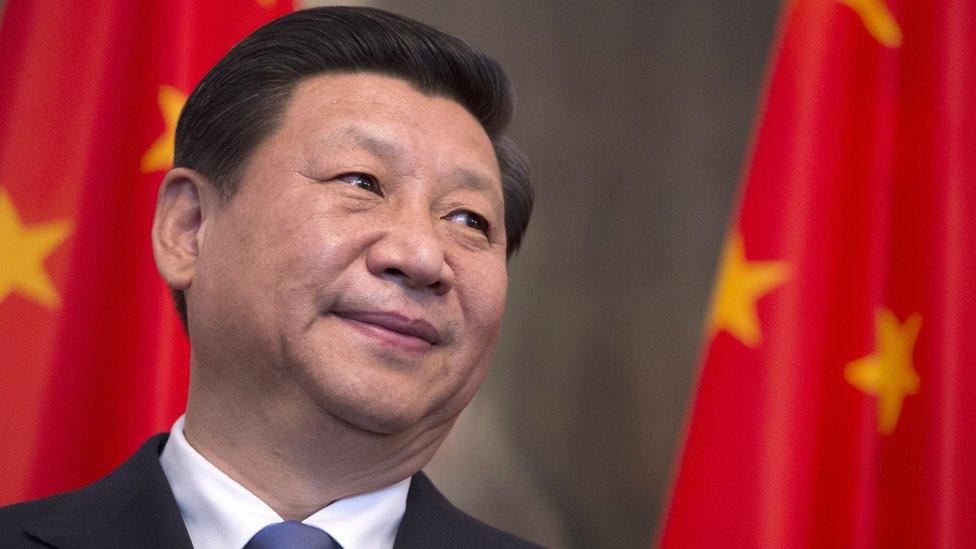

Under Xi Jinping, Beijing is seeking increasing control over Hong Kong

The city has its own laws and its residents enjoy civil liberties unavailable to their mainland counterparts.

Hong Kong has entered into extradition agreements with 20 countries, including the UK and the US, but no such agreements have been reached with mainland China despite ongoing negotiations in the past two decades.

Critics have attributed such failures to poor legal protection for defendants under Chinese law.

Reporting by Jeff Li, BBC Chinese.

- Published4 September 2019