Hong Kong protests: Did violent clashes sway public opinion?

- Published

The actions of protesters who burst into Hong Kong's Legislative Council have divided opinion

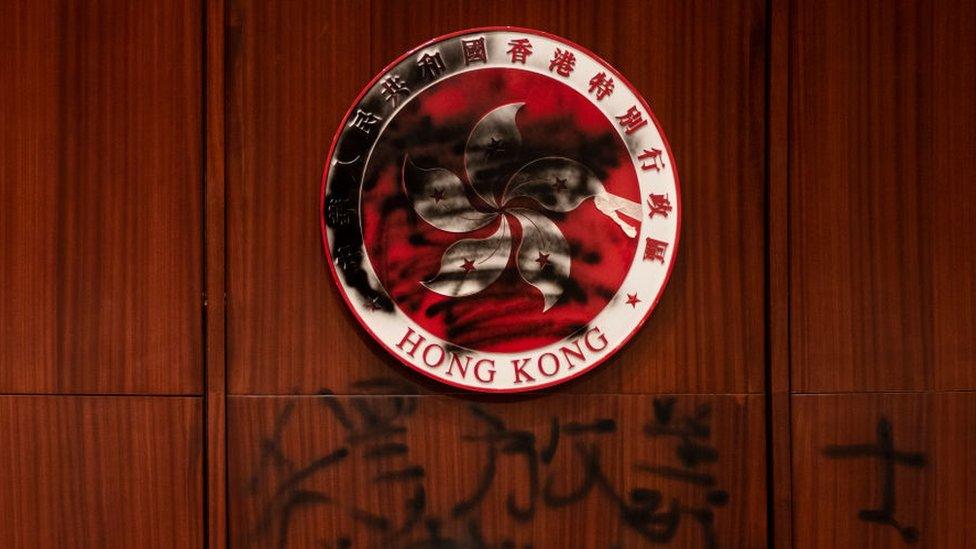

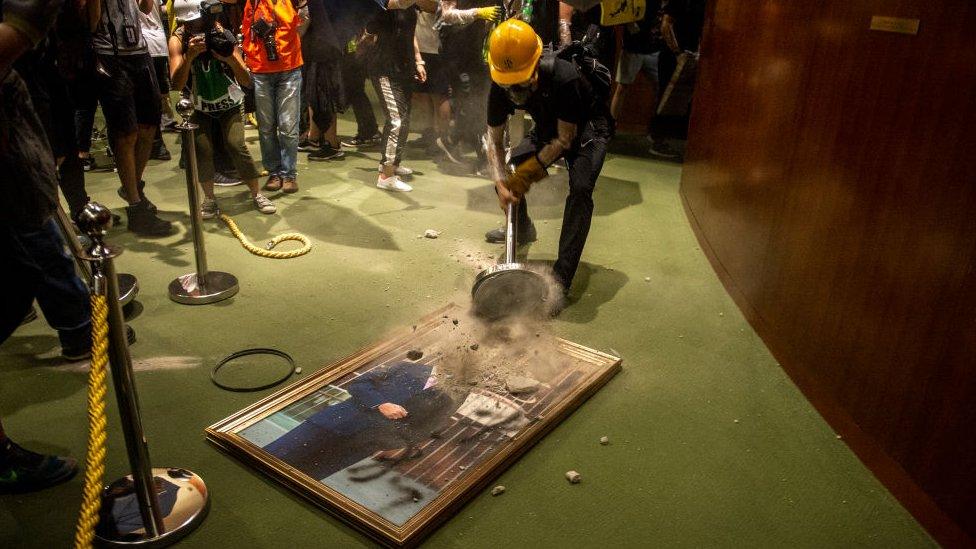

A splinter group of protesters smashed their way into Hong Kong's legislative council on Monday, breaking glass walls, defacing paintings and spraying graffiti. It was denounced by the city's leader as an extreme use of violence, but how do residents feel about what happened?

On the roads that surround Hong Kong's Legislative Council (LegCo) small groups of passers-by take photos of what is now being described as a crime scene. Some peel hand-written post-it notes from walls as memorabilia.

Twenty-four hours earlier, the bustling six-lane carriageway that surrounds the government offices was held ransom by thousands of young protesters demanding the withdrawal of a controversial extradition law.

Armed with makeshift barricades, they stormed Hong Kong's parliament - spraying graffiti on walls, and working in teams to deface symbols of Hong Kong's law-making body.

"I can understand the frustration and can also understand the opposition to what happened," said one Hong Kong resident, leaning on the fencing of a bridge overlooking the government offices.

"They avoided hurting anyone, they put up posters, they defaced the symbols of Hong Kong. I see it as organised riots. It was targeted at symbolism."

The regional emblem of Hong Kong was defaced

"I don't support them. They did the wrong thing," said a man who didn't want to be identified.

"I am glad that no one died," another man said.

In recent weeks millions of Hong Kong residents have marched on the streets, united in opposition to a now-suspended extradition law which critics fear could spell an end to Hong Kong's judicial independence.

Even portraits of legislators were not safe

The peaceful protests have transformed into a youth-led civil disobedience campaign, aimed at disrupting government departments.

The end justifying the means?

On Tuesday Beijing condemned the ransacking of the LegCo building. But the storming of the law-making body has garnered a mixed response from those who oppose the extradition law.

"Most of my friends support the young people because they think only this kind of action can achieve the goal. As a mum I only support protesting in a peaceful way," said a housewife identified only as Sarah, who has attended many of the peaceful marches against the extradition law.

"Their actions have deepened the gap between the young people and the senior citizens.

"Most of Hong Kong people support the action to fight for the democracy of Hong Kong, but they don't want to see any overwhelming violent action. I don't support the violence," she said.

The 22nd anniversary of the former British colony's return to China was marked on 1 July. Organisers claim that more than 500,000 took part in an annual pro-democracy march, ten times the number of protesters who attended last year's demonstration.

Organisers say over half a million took part in a pro-democracy march on 1 July

"We are fighting with a government that isn't elected by the public and a communist system. Protests like in your country don't work here," says Chris Yu, a secondary school teacher who has also joined many of the peaceful marches.

On 1 July, he saw his own students on the streets surrounding government buildings.

"Somehow, I agree", says Mr Yu. "I didn't agree in the past but now I do. I somehow realise we may need some new ways to protest."

A day that started with champagne toasts ended with tear gas

Pro-democratic lawmakers argue that protesters acted out of despair. But many fear that the violence could play into the hands of the pro-Beijing camp.

"I do not support violence. I think that we should use vote to continue the struggle. This is the second battlefield. But I will still fully support them," said a shop owner who took part in the peaceful march.

"This class of young people are fighting for something the adults have not dared to fight for so many years. How can I not be touched by them?"

- Published2 July 2019

- Published2 July 2019

- Published21 May 2020

- Published17 June 2019