Hong Kong protests: What LegCo graffiti tells us

- Published

The BBC's Nick Beake inside the Legislative Council after protests in 2019

On Monday night, protesters in Hong Kong broke into the parliamentary building, smashing metal shutters and breaking glass.

They ransacked the main chamber of the Legislative Council - known in Hong Kong as LegCo - in what Chief Executive Carrie Lam called an "extreme use of violence".

The group were a small branch of a largely leaderless protest movement sparked by a controversial, now suspended, extradition bill.

The protesters were evicted after a few hours, but the graffiti they left behind tells us a lot about the evolving nature of these protests.

The defacing of the emblem

Hong Kong is a semi-autonomous part of China, and LegCo is where its government sits and bills are debated and passed.

Protesters are now showing their anger and frustration through graffiti

Central on the main wall of the chamber is the territory's emblem. In English, it says Hong Kong, but in Chinese it reads: "The Regional Emblem of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China".

The protesters defaced a portion of the emblem bearing the word "China", leaving the Hong Kong part of the emblem untouched.

Under the Basic Law, in place since Hong Kong was handed back to China by the UK in 1997, Hong Kong is guaranteed a level of autonomy and has freedoms not available in mainland China. It keeps its own judicial independence, its own legislature and economic system.

But critics say this is under threat from an increasingly assertive China.

The extradition bill, that would have enabled suspects in Hong Kong to be sent to China, was cited as proof of this, sparking massive protests.

The bill has been suspended - and is unlikely ever to pass. But the defacing of the bill is indicative of the anger many in Hong Kong have towards China.

The colonial flag

The protesters also draped a colonial-era Hong Kong flag on the podium inside LegCo.

It's a sign of Hong Kong's history as a British colony and is being seen as a message to the former colonisers, calling on the UK to hold China to account.

The British colonial flag was draped inside the government's legislative council building

One Hong Kong journalist said the flag was not a sign, as some have suggested, that the protesters want a return to British rule.

"Whatever the British Hong Kong flag means today, Beijing wouldn't be pleased to see it. And that might have been the point of putting it in front of the world's cameras," said Inkstone editor Alan Wong on Twitter.

Tyranny banner

This black banner which was installed over the podium reads: "There are no rioters, only a tyranny."

"There are no rioters, only a tyranny", reads this sign

The Hong Kong government described violent clashes on 12 June between protesters and police as a riot - something else that has angered the demonstrators.

The term rioting is a serious one, it's an offence punishable by up to 10 years in jail. Protesters want the government to drop this term.

The sunflower movement

The phrase "Hong Kong's sunflower" can also be seen on the walls.

"Hong Kong's Sunflower"

It's a reference to the Sunflower Movement protests that took place in Taiwan in 2014 when a controversial trade agreement led students and activists to occupy Taiwan's parliament.

They were protesting against what they said was a sign of Beijing's growing influence over Taiwan - the same thing they say is happening in Hong Kong right now.

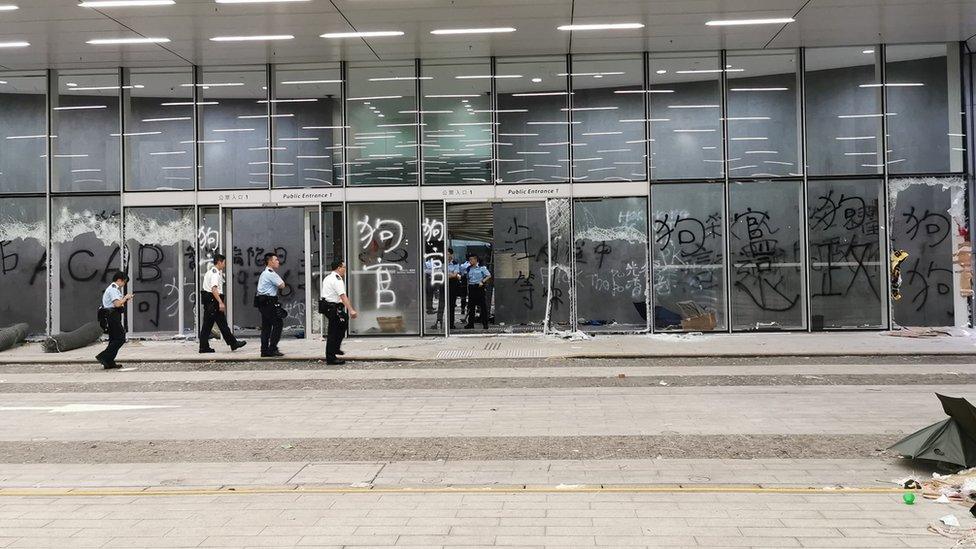

'Dog officers'

References to the police being "dogs" were sprayed repeatedly on these glass doors and elsewhere.

The phrase "dog officers" can be seen scrawled all over the glass doors

Protesters have frequently described the city's police force as "lapdogs" of the government, occasionally of Beijing too.

It was 12 June that proved to be a turning point in the relationship between the police and the people.

It first started out as another protest, but protesters and police officers soon clashed on the streets. Protesters were seen throwing items at police, who responded by spraying tear gas and firing rubber bullets.

Joshua Wong: Why activists broke into parliament

Footage has been circulating showing some officers dragging protesters and beating them with batons. Human Rights Watch called it a "well-documented use of excessive force against peaceful protesters".

Protesters have been demanding an independent inquiry into alleged police brutality.

But there have also been large demonstrations in support of the Hong Kong police.

The police commissioner has rejected allegations of excessive force, saying many police officers have been injured in the unrest.

'It was you who taught me'

A slogan sprayed on one of the columns in the Legislative Council reads: "It was you who taught me peaceful marches did not work."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It appears to be directed at Hong Kong's leader Carrie Lam, who despite protests of up to a million people prior to 12 June, had remained adamant that the extradition bill would not be suspended.

The government later backed down and suspended the bill, and Ms Lam indicated that it would likely not pass.

However the bill has been perceived as being part of a wider agenda that aims to move Hong Kong further down a path of becoming a fully "Chinese city", without its unique freedoms.

'Freedom'

The Chinese characters for "freedom" - sprayed on this screen in LegCo - sum up why people in Hong Kong say they are protesting.

This simply reads 'Freedom'

Under a deal struck with Britain that saw Hong Kong return to China in 1997, the city was guaranteed to enjoy "a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs" for 50 years.

The Basic Law ends in 2047, and what happens to Hong Kong's autonomy after that is unclear, which is fuelling the protesters' sense of urgency.

- Published30 June 2019

- Published21 May 2020

- Published2 July 2019

- Published17 June 2019