Hong Kong protests test Beijing's 'foreign meddling' narrative

- Published

A few months ago a Chinese official asked me if I thought foreign powers were fomenting Hong Kong's social unrest.

"To get so many people to come to the streets," he mused, "must take organisation, a big sum of money and political resources."

Since then, the protests sparked at the beginning of Hong Kong's hot summer have raged on through autumn and into winter.

The massive marches have continued, interspersed with increasingly violent pitched battles between smaller groups of more militant protesters and the police.

The toll is measured in a stark ledger of police figures that, even a short while ago, would have seemed impossible for one of the world's leading financial capitals and a bastion of social stability.

More than 6,000 arrests, 16,000 tear-gas rounds, 10,000 rubber bullets.

As the sense of political crisis has deepened and divisions have hardened, China has continued to see the sinister hand of foreign meddling behind every twist and turn.

The 'grey rhino'

In January, China's supreme political leader Xi Jinping convened a high-level Communist Party meeting focused on "major risk prevention".

He told the assembled senior officials to be on their guard for "black swans" - the unpredictable, unseen events that can plunge a system into crisis. But he also warned them about what he called "grey rhinoceroses" - the known risks that are ignored until it's too late.

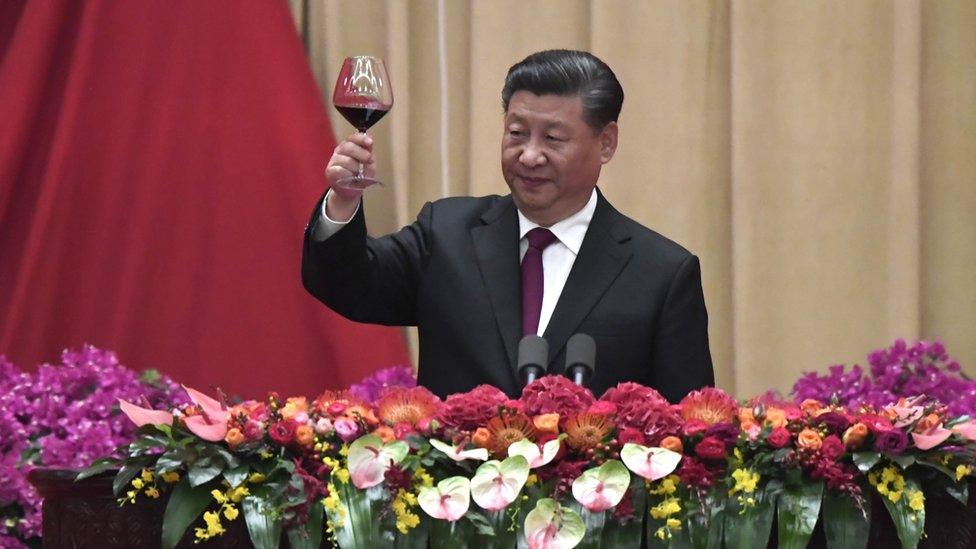

Xi Jinping toasts 70 years of Communist Party rule, while protests rage in Hong Kong

While state media reports show the discussions ranging over issues from housing bubbles to food safety, external, there's no mention at all of Hong Kong.

And yet the seeds were already being sown for what has become the biggest challenge to Communist Party rule in a generation.

A few weeks after the meeting, the Hong Kong government, with the strong backing of Beijing, introduced a bill that would allow the extradition of suspects to mainland China.

Opposition to the bill was immediate, deep-seated and widespread, driven by the fear that it would allow China's legal system to reach deep inside Hong Kong.

Despite assurances that "political crimes" would not be covered, many saw it as a fundamental breach of the "one country, two systems" principle under which the territory is supposed to be governed.

It wasn't just human rights groups and legal experts expressing alarm, but the business community, multinational corporations and foreign governments too, worried that overseas nationals might also find themselves targeted by such a law.

And so, the first claims of "foreign meddling" began to be heard.

Protests have ranged from peaceful family events to large-scale, armed street violence

On 9 June, a massive and overwhelmingly peaceful rally against the bill was held, with organisers putting the attendance at more than a million.

The accusations made in person by officials, like the one mentioned earlier, were echoes of a narrative being taken up in earnest by China's Communist Party-controlled media.

The morning after the march, an English language editorial in the China Daily raised the spectre of "interference"., external

"Unfortunately, some Hong Kong residents have been hoodwinked by the opposition camp and their foreign allies into supporting the anti-extradition campaign," it said.

From the protesters' point of view, the dismissal of their grievances as externally driven explains, to a large extent, what happened next.

The city's political elite, backed by Beijing and insulated from ordinary Hong Kongers by a political system rigged in its favour, demonstrated a spectacular failure to accurately read the public mood.

The trauma of Hong Kong's teenage protesters

Three days after the march, with Hong Kong's leader, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, insisting she would not back down, thousands of people surrounded the Legislative Council building where the bill was being debated.

It was on the same spot just outside the chamber, less than five years earlier, that a phalanx of trucks with mechanical grabbers had begun scooping up rows of abandoned tents.

To the sound of the snapping of poles and the crunching of bamboo barricades - the detritus of weeks of protest and occupation - 2014's pro-democracy demonstrations finally ran out of steam.

Now the proposed law, one that may once have been seen as relatively inconsequential, was about to reignite the movement.

The protesters threw bricks and bottles, the police fired tear gas and by the evening of 12 June, Hong Kong had witnessed one of its worst outbreaks of violence in decades.

More than 6,000 people have been arrested through the months of increasingly violent unrest

No-one could be in any doubt that the Umbrella Movement, with its demands for wider democratic reform, was back with a vengeance.

The few concessions - first the suspension and finally the withdrawal of the bill - came too late to stop the cycle of escalating violence from both the protesters and the police.

Beijing is right to point out that there are plenty of Hong Kongers who deplore the mask-clad militants building barricades, vandalising public property and setting fires.

Some of them are ardent supporters of Chinese rule, others are simply being pragmatic, believing that violence will only provoke the central government into intervening more strongly in Hong Kong's affairs.

First-time voters and candidates ousted seasoned veterans in some constituencies

But the authorities were stunned last month by a test of the true strength of those viewpoints, when - on a record turnout in local elections - the pro-democracy camp swept the board.

The poll gave its candidates almost 60% of the total share of the votes.

At first there was an astonished silence from mainland China, which had genuinely thought the pro-Beijing side would win.

The initial news reports mentioned only the conclusion of the voting, not the results, but then came a familiar refrain.

The state-run Xinhua news agency blamed "rioters" conspiring with "foreign forces".

"The politicians behind them who are anti-China and want to mess up Hong Kong reaped substantial political benefits," it said.

As proof of interference, China cites cases of foreign politicians voicing support for democracy, external or raising concerns about its erosion under Chinese rule.

It has also blamed Washington for passing a law mandating an annual assessment of Hong Kong's political freedoms as a pre-condition for continuing the territory's special trading status.

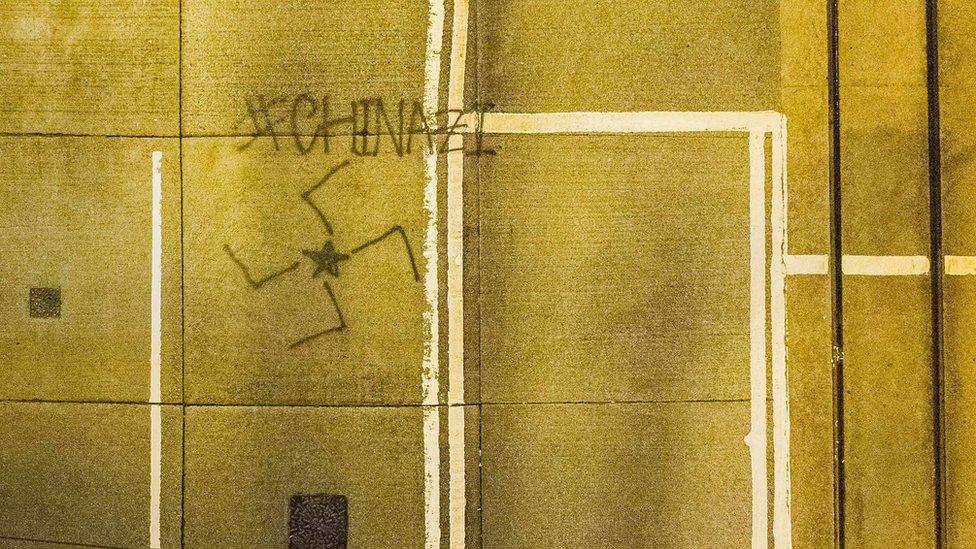

Hong Kong's protesters have adopted the word "Chinazi" to display their views towards Beijing

Xinhua has denounced it as "a malicious political manipulation, external that seriously interferes with Hong Kong affairs".

But no evidence has been produced of any outside forces co-ordinating or directing the protests on the ground.

In reality, the young, radical protesters, with the ubiquitous use of the portmanteau "Chinazi" in their street graffiti, appear as much motivated by statements from Beijing as they are from Washington.

The very institutions - independent courts and a free press - that are supposed to be protected by the "one country, two systems" formula, are derided by the ruling Communist Party as dangerous, foreign constructs.

Where once Hong Kongers might have hoped that China's economic rise would bring political freedoms to the mainland and a closer alignment with their values, many now fear the opposite.

Mass detention camps in Xinjiang, a wider crackdown on civil society, and the abduction of Hong Kong citizens for perceived political crimes have all underlined the concern that their city is now ruled by political masters inherently hostile to the very things that make it special.

And any appeal to universal values as underwriting Hong Kong's side of the "two systems", is anathema to Beijing, one that it rejects by conflating it with outside foreign meddling.

Despite earlier fears, the central government seems unlikely to send in the army - a move certain to provoke even more of an international outcry.

Mainland Chinese soldiers deployed in Hong Kong have remained in their barracks throughout the protests

But nor can it offer a political solution.

Giving the pro-democracy movement any more of what the Communist Party strains every fibre of its organisational structure to deny to the mass of Chinese people is impossible.

Its values are stability and control, not freedom and democracy, and it struggles to understand how anyone would choose the latter over the former.

So Beijing finds itself bound by a sense of historical destiny to a territory with which it is - in large part - in deep ideological opposition.

It is a tension that has not gone unnoticed elsewhere in the region, in particular, in Taiwan, the self-governing island that China considers a breakaway province.

Hong Kong's experience of one country, two systems, the Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen has suggested, has shown that authoritarianism and democracy cannot coexist.

Referring to the prospect of a similar formula being foisted on Taiwan she tweeted, in Chinese characters, the phrase bu ke neng - "Not a chance".

The history behind Hong Kong's identity crisis and protests - first broadcast November 2019

- Published15 August 2019

- Published1 July 2022

- Published11 October 2019