China internet: Top talking points of 2019 and how they evaded the censors

- Published

China has one of the most tightly controlled internet environments in the world, but despite this its 854 million internet users yet again in 2019 found ways to challenge the government or talk about the issues they want to discuss.

This year, China has seen a reignited #MeToo movement, young people have challenged unethical working hours, and the nation has united in concern against the aggressive rollout of AI technologies.

But the government has also promoted its own interests related to the environment, the business sector, and of course, in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong's demonstrations have dominated discussions among Chinese online

In the last six months, this one topic has dominated news coverage on social media platforms both inside and outside mainland China.

In fact the large-scale Hong Kong protests, which attracted international media attention in early June, led to the word "Hong Kong" initially becoming a censored search term on 9 June, external. When the protests first began, the Beijing government censored any reference to them, but after it became clear they wouldn't go away, official media mounted a heavy media campaign to portray the demonstrations as violent with "shades of terrorism".

Hashtags including #SupportTheHongKongPolice and #ProtectHongKong were aggressively rolled out by government media on the Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo.

In contrast, on Twitter and Instagram, protestors used the hashtag #FightForFreedomStandWithHK and #GloryToHongKong - slogans that have subsequently become associated with the demonstrations.

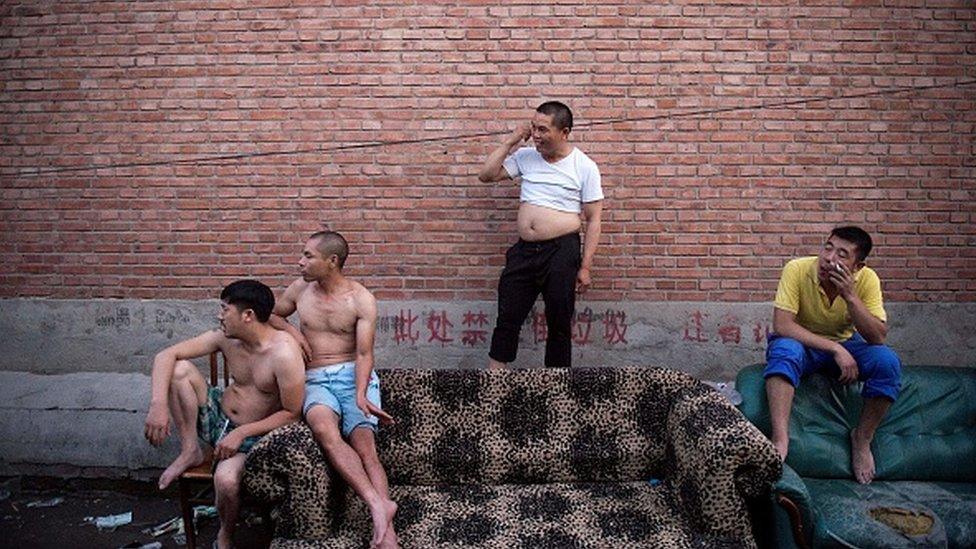

'Civilised behaviours'

A number of Chinese cities are moving to make exposed bellies an example of 'uncivilised behaviour'

Ahead of China rolling out a controversial social credit system in 2020, as a means of assessing citizens' economic and social reputation, one phrase has repeatedly cropped up: the need for more "civilised behaviours".

The Beijing government has left it to regions to determine how they implement this, and as a result, a number of regulations encouraging citizens to be "civilised" have come into effect around the country, but have also left people scratching their heads.

In July, the eastern Chinese city of Jinan banned topless men and the "Beijing bikini", external: the habit of men exposing their bellies by rolling up their shirt.

In May, the capital targeted manspreading and eating on the subway, external, and eastern Nanjing has warned jaywalkers - pedestrians who cross the road at a red light - that their social credit could be impacted if they failed to wait for the little green man., external.

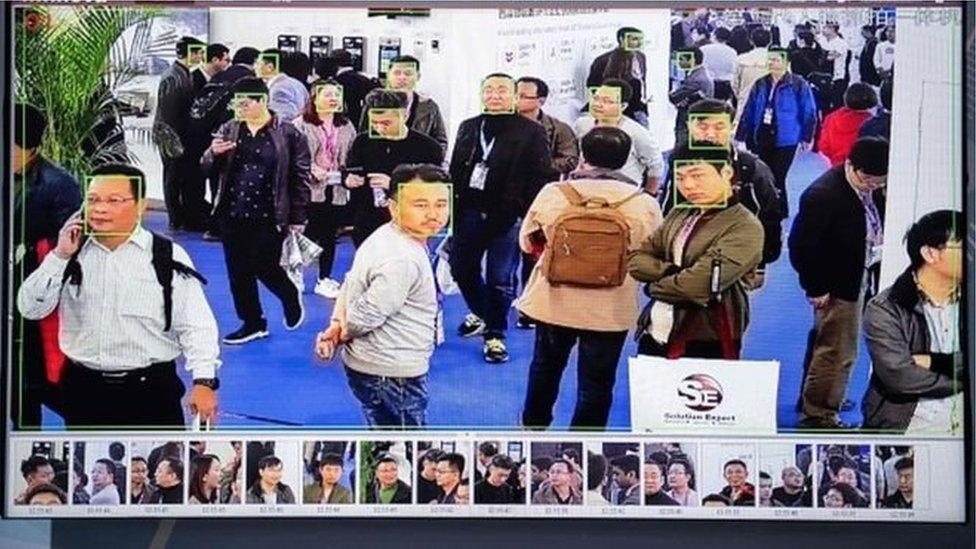

Facial recognition

Facial recognition is entering more and more Chinese industries - but people aren't impressed

China's development of artificial intelligence technologies has rocketed this year, but online topics related to the rise of facial recognition technologies have raised eyebrows and ignited a lot of concern online.

Early in the year, payment service Alipay extensively worked with retail stores to enable consumers to buy products using facial recognition. But by July, it announced that it was adding beauty filters to facial scan payment devices, noting that the majority of consumers were not comfortable with the technology, and hated seeing their face to pay., external

Facial recognition has been mocked for its imperfections. In May, a security camera wrongly identified a man scratching his face as taking a phone call.

And there have been a string of controversies related to platforms being unnecessarily intrusive when collecting consumers' facial data.

In July, a vlogger was mocked after facial filters she had used revealed her to be a much older woman. In September, an app called ZAO was shut down, after it allowed users to insert their faces in place of film and TV characters, and sparked fraud and privacy fears.

And in November, a law professor sued a wildlife park, after it suddenly enforced facial recognition as a prerequisite for entry.

'996'

Jack Ma says his Alibaba business wouldn't have been successful if he hadn't worked extensive overtime

Late last year, the term "996" cropped up on a number of social media microblogs and forums, originally by workers in China's tech industry as a subtle way to vent their frustrations at the excessive amount of work they were expected to do.

The Chinese censors struggle to censor number sequences, given that they can often be innocuous. Consequently, Weibo users were able to use the term "996" to complain openly that their employer was violating China's labour laws by making them work some 72 hours a week: from 9am to 9pm, six days a week.

But the phrase has now seen expanded usage beyond the tech industry, especially among China's young, who complained that overtime has become an epidemic.

However, some of the country's best-known entrepreneurs have defended the "996" system, crediting it with enabling their businesses to surpass others. These include China's richest man, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, and fellow tech entrepreneur Richard Liu.

985,211,996,251

Another of China's giant companies has been dragged into the number scandal too. The string of numbers 985,211,996,251 looks like a website address, but it's actually being used to talk about a scandal involving a former employee of tech giant Huawei.

The first and second set of numbers refer to China's top universities, where many tech employees will come from - 985/221 in the country's national university rankings; 996 is the number of hours they're usually expected to work, and the 251 represents the number of days former Huawei employee Li Hongyuan spent in police custody after a disagreement with his employer.

Li was sent to prison for asking for severance pay having worked 13 years for the company. He was accused of extortion. Prosecutors freed him in August, after finding insufficient evidence to back Huawei's claim.

The case has tarnished the reputation of Huawei, despite the huge wave of domestic patriotism towards it following the arrest of its CFO Meng Wanzhou in Canada a year ago.

Sexual assault

Beauty vlogger Yuyamika encouraged others to break their silence on experiences of domestic violence

Last year, following international momentum of the #MeToo movement, China saw a number of women trying to use the hashtag to mention their own experiences of sexual abuse, but they were swiftly censored online.

This year, however, women in China have made it difficult for government censors to filter their experiences of sexual assault, by sharing footage that they have covertly filmed of their own experiences.

It has been increasingly common, and an almost daily occurrence in recent months, for videos to appear on Sina Weibo, which quickly go viral, of women being assaulted by their partners. The All-China Women's Federation says that as many as 30% of China's married women - some 90 million women - have suffered some form of domestic violence, external.

In November, a beauty vlogger Yuyamika called on her million of followers to be "no longer silent" on domestic violence.

And there have also been calls among student communities to out people in positions of power for abusing women.

In December, students at universities in Beijing, external and Shanghai, external united online to detail their experiences of sexual assault at the hands of their professors. This led to two university professors being sacked.

Recycling

VR games went viral for showing Chinese people that recycling could be fun

The environment has become a growing topic of international interest this year, and in July, the largest and most populous city in the world, Shanghai, took the bold move to enforce strict new recycling regulations.

It demanded that people divide their waste into four different kinds, or else face hefty fines. Additionally restaurants and food delivery businesses have banned plastic cutlery and hotels have banned disposable goods.

The same month, the hashtag #DividingRubbishChallenge went viral, with the government promoting ways that people could remember which product goes in which bin.

Social media users across the country animatedly discussed viral songs, board games, and even a video of a man playing a virtual reality rubbish dividing game.

And there has been a widespread national consciousness to be more environmentally friendly. The official CGTN broadcaster says that 46 major Chinese cities will be following in Shanghai's footsteps by the end of 2020, external.

'Boycott…'

Some say they are boycotting the 2020 film Mulan after actress Liu Yifei posted support for Hong Kong's police

This year, there have been repeated calls - largely state-orchestrated - to boycott either individuals, products or franchises, if they are seen to be anti-China.

A number of international brands were slammed by Chinese media in August, because they referenced either Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan as separate countries or regions: including luxury brands Versace, Coach and Givenchy.

China went further this year, risking antagonising its international sports fans by indicating that it would also not be tolerant of huge sporting franchises. After basketball manager Daryl Morey tweeted his support for Hong Kong protestors in October, China outright banned NBA games on its state broadcaster.

In December, a tweet by Arsenal football player Mesut Ozil also led to Chinese TV removing Arsenal games from its sports channels.

There have also been media counter campaigns overseas in retaliation to China's cancel culture.

In March, Indian users used the hashtag #BoycottChineseProducts after China initially blocked a bid to designate Pakistan's Masood Azhar, the leader of a group that carried out a Kashmir suicide bombing, a terrorist.

In August, people on Twitter used the hashtag #BoycottMulan after Chinese actress Liu Yifei expressed her support for the Hong Kong police.

Additional reporting by Yashan Zhao

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

Journalist Karoline Kan explains how Chinese social media is censored.

- Published3 December 2019

- Published28 August 2019

- Published8 October 2019

- Published16 October 2017