Chinese censors take aim at AirDrop and Bluetooth

- Published

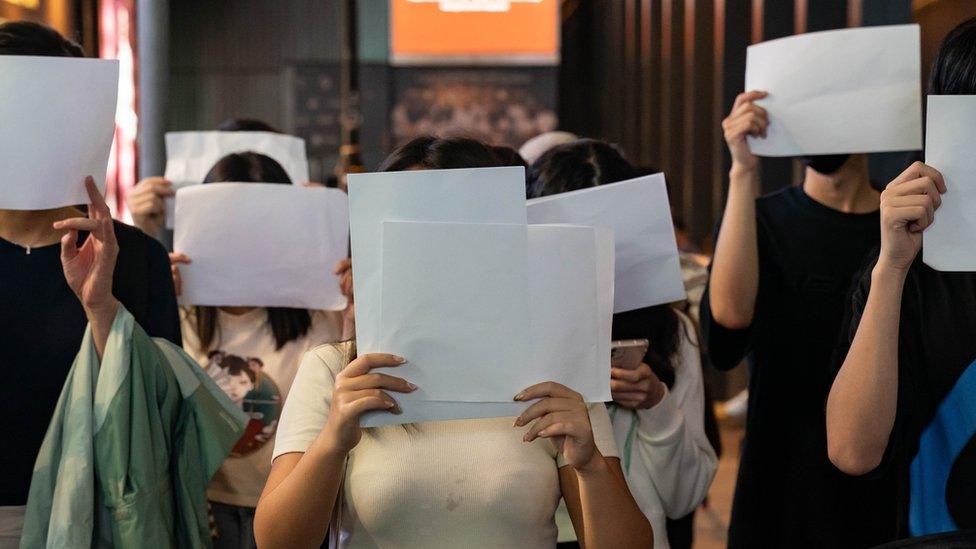

Protests are much harder to sustain in the face of China's censorship machine

China wants to restrict the use of mobile file-sharing services such as AirDrop and Bluetooth in a move that will expand its censorship machine.

The national internet regulator on Tuesday launched a month-long public consultation on the proposals.

They want service providers to prevent the spread of illegal and "undesirable" information, among other things.

Activists fear that this will further hinder their ability to mobilise people, or share information.

Bluetooth, AirDrop and such file-sharing services are crucial tools in China, where the so-called Great Firewall has resulted in one of the mostly tightly-controlled internet regimes.

In recent years, anti-government protesters have often turned to AirDrop to organise and share their political demands. For instance, some activists were sharing anti-Xi Jinping posters using this tool on the Shanghai subway last October - just as the Chinese president was awaiting a historic third term as the country's leader.

AirDrop is especially popular among activists because it relies on Bluetooth connections between close-range devices, allowing them to share information with strangers without revealing their personal details or going through a centralised network that can be monitored.

But soon after Mr Xi secured a third term, Apple released a new version of the feature in China, limiting its scope. Now Chinese users of iPhones and other Apple devices are restricted to a 10-minute window when receiving files from people who are not listed as a contact. After 10 minutes, users can only receive files from contacts. Apple did not explain why the update was first introduced in China, but over the years, the tech giant has been criticised for appeasing Beijing.

The latest move, activists say, suppresses the few remaining file-sharing tools at their disposal, although China has defended these regulations in the name of national security and public interest.

Proposals unveiled by the Cyberspace Administration of China on Tuesday require users to "prevent and resist the production, copying and distribution of undesirable information". Those who do not comply must be reported to the authorities, the draft regulations say.

Users must also register with their real name before they can use these file-sharing services, and the service must be turned off by default.

Read more of our coverage of protests in China:

"The authorities are desperate to plug loopholes on the Internet to silence opposing voices," says Netherlands-based human rights activist Lin Shengliang, adding that more such regulations could follow.

Mr Lin left China after he was detained in Shenzhen for printing T-shirts carrying a quote from an exiled Chinese businessman and political activist.

"This is China moving towards 1984," he says, referring to George Orwell's cautionary tale against totalitarianism.

Phone and app developers who want to continue operating in China will have to play by the new rules - or be culled from app stores, said a software engineer who wanted to stay anonymous.

"Like WeChat, developers will have to provide censorship capabilities and be subject to take-down orders. These new rules could be a show-stopper for non-Chinese applications," said the man.

Artwork depicting China's mystery "Bridge Man" protester proliferated online last year

The new regulations restrict the very features that activists find useful about file-sharing - such as being able to share content with strangers' without waiting for them accept the files; or their permission to pair devices.

The regulations include a feature that lets users put specified contacts on a "black list", which effectively lets them block certain devices from sharing files. There is also a provision for users to register complaints.

Censors already relentlessly scrub photographs, footage and comments online, while maintaining a growing list of banned words. Resourceful activists have been finding new ways to get around this but even those few cracks in the Great Firewall - like AirDrop - are now slowly being plugged.

While users may still be able to bypass such restrictions using virtual private networks or VPNs, activists fear that the number would be too small to make an impact.

Yet Mr Lin believes that China's recent wave of protests, sparked by zero-Covid measures, mark a new political awakening that will not be put out so easily.

"We will find new ways to speak up," he said. "If we are bold and we stand together, we will not be silenced."

Related topics

- Published5 June 2023

- Published28 November 2022