Viewpoint: Manmohan Singh has stayed on too long

- Published

- comments

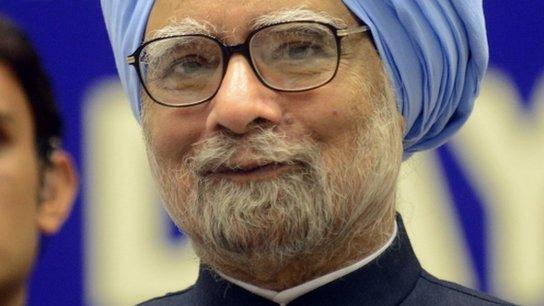

Manmohan Singh is one of the architects of India's economic reforms

India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is 80. Writer and historian Ramachandra Guha assesses his performance in office.

In April 1958, Jawaharlal Nehru went for a holiday in the hills to sort out his future.

After 10 bruising years as India's prime minister, he wanted a spell as a private citizen.

He thought he should give up his job, catch up with old friends and with his reading, and go on a "slow pilgrimage" to different parts of the country. In the end, Mr Nehru was persuaded to reconsider his decision, and stay on in office.

Had Mr Nehru retired in 1958 he would be remembered as not just India's best prime minister, but as one of the great statesmen of the modern world.

He had helped nurture a plural, multi-party democracy against massive opposition and in the face of widespread scepticism. He had forged innovative and independent-minded economic and foreign policies. He had made sure that India would not be a Hindu Pakistan.

After 1958, however, Mr Nehru's problems began.

Bruised reputation

The first major corruption scandal (the Mundhra affair), external took place under his watch; then he acquiesced in the shocking dismissal of an elected Communist state government in Kerala.

A spate of border conflicts erupted, culminating in the humiliating defeat at the hands of the Chinese Army in 1962. When Mr Nehru died in May 1964, his reputation lay in tatters.

Manmohan Singh is no Mr Nehru; but his term in office bears some curious resonances with that of his illustrious predecessor. His well-wishers had hoped he would retire in 2009, and perhaps the thought crossed his mind itself.

Mr Nehru's problems began after 1958

After the Gujarat riots and the vulgar 'India Shining', external campaign, his compatriots needed a safe, steady, understated hand; this Manmohan Singh and his government had provided.

Religious tempers had been calmed, government functioning made more transparent (through the right to information law, external), and a series of welfare measures for the rural poor (pre-eminently, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme, external) initiated. He had done his job; it was time now to make way for a younger man (or woman).

Had Manmohan Singh retired in 2009, history would have remembered him as one of the two main architects (PV Narasimha Rao being the other) of economic liberalisation in India; and as a moderately successful prime minister.

But, unable to resist the lure of office, he stayed on.

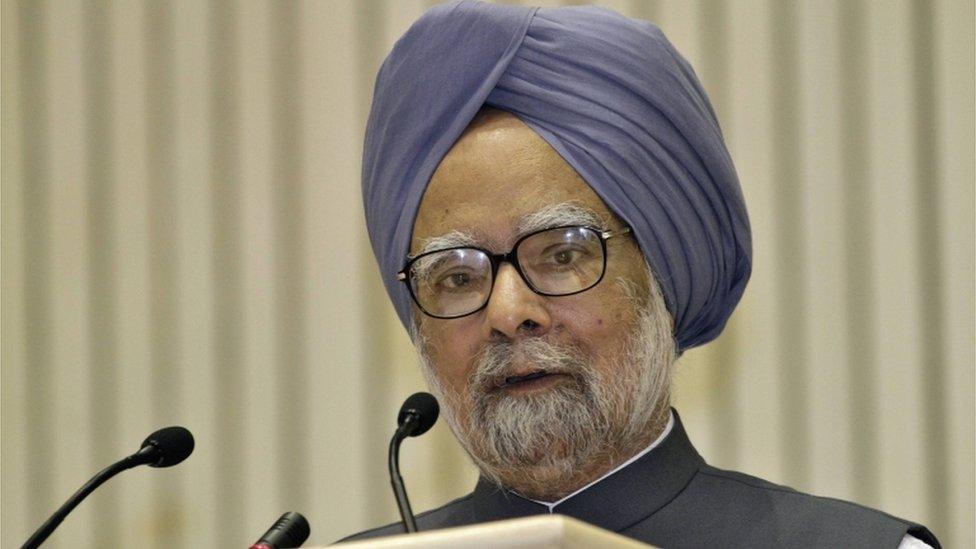

In his second term, he has presided over what is arguably the most corrupt government in Indian history.

The series of scandals - Commonwealth Games, telecoms spectrum, 'Coalgate' - that he has failed to prevent, detect or take prompt action over have massively damaged his party and his government and irretrievably dented his own reputation.

In the 1990s, in the first flush of the liberalisation he helped initiate, those entrepreneurs with the most creative ideas tended to do best; now, with him as prime minister, it is the cronies with the best contacts who flourish.

The corruption apart, the second term of the Congress-led government has also been marked by apathy and incompetence.

There have been no imaginative measures of the right to information law or the jobs for work scheme. In 2004, when Manmohan Singh, himself a trained economist, became prime minister, there were great hopes that he would modernise administration, bring well-qualified professionals into public service, and insulate civil servants and police officers from political interference.

He has done nothing of the kind; rather, he has been unwilling to disturb in any way the networks of patronage that have so grievously damaged the ability of the Indian state to provide decent education, health care and public safety to its citizens.

Political authority

Slow, timid, status quoist, and, above all, corrupt; these are the terms in which Manmohan Singh and his second government will be remembered.

It need not have turned out that way.

But then the Indian case is illustrative of a much wider phenomenon; of once competent, once admired politicians who stay on too long in office and see their reputation diminish as a result.

This may be why the United States introduced a two-term limit for their presidents.

Across the Atlantic, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, seen as modernising go-getters in their early years in office, had eventually to be defenestrated by their own colleagues to save their party's reputation.

In August 2011, in an article for the Hindustan Times, external, I urged the prime minister to resign.

Mr Singh's government has been under pressure for most of its second term

His apathy, age and lack of independent political authority were increasingly evident.

"It is time," I wrote, that Manmohan Singh "made way for a younger man or woman, for someone who has greater political courage, and who is a member of the Lok Sabha [lower house] rather than the Rajya Sabha [upper house]. As things stand, with every passing day in office his reputation declines further. So, more worryingly, does the credibility of constitutional democracy itself."

When I wrote this I knew that India was not the United Kingdom.

Unlike in the case of Mrs Thatcher or Mr Blair, the Congress party, itself timid and status quoist, was not likely to ask Manmohan Singh to leave office.

My appeal, rather, was to his own reason and background; surely, as a well read and historically minded intellectual himself, he knew it was now time to retire from politics?

The great Indian cricketer Vijay Merchant, external, when asked why he had retired from the game after scoring a century in his last Test innings, answered: "I wanted to go when people asked 'Why' rather than 'Why Not'?"

This is a lesson few cricketers have heeded, and even fewer politicians. In staying on so long in office - despite the cost to his party, his government, his country and himself - Manmohan Singh is in the rather elevated company of Winston Churchill, Charles de Gaulle, Margaret Thatcher and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Ramachandra Guha's books include India after Gandhi and Makers of Modern India. He lives in Bangalore. The views expressed in this article are his own.

- Published11 March 2015

- Published12 June 2012

- Published21 September 2012

- Published26 September 2012