Viewpoint: What was the real reason behind India's reforms?

- Published

India has just opened its retail sector to global supermarket chains such as the US giant Wal-Mart which operates this wholesale outlet with India's Bharti

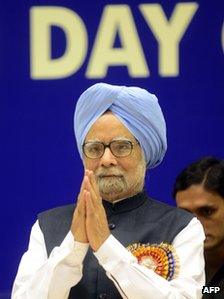

There has been a lot of speculation about why India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh pushed through controversial economic reforms recently and risked his government's survival.

Last week, a key ruling coalition ally, the Trinamool Congress party, withdrew support in protest against the government's decision to open the retail sector to global supermarket chains and raise diesel prices.

The government has been reduced to a minority, but its majority in parliament is not at immediate risk as it still has the support of some regional parties.

Many believe Mr Singh's reforms rush is an attempt to refurbish his image and energise his colleagues.

Others say it was to give a forceful answer to his critics in the foreign media, and divert attention from corruption charges against his government.

However, in his address to the nation on 21 September, the prime minister hinted at the real reason why the government opted for these contentious decisions.

If we had not acted, he said, it would have meant "a loss of confidence in our economy".

'Junk status'

What he left unsaid was that this would indeed have happened if the global rating agencies like Standard & Poor's (S&P), had downgraded India's investment status to "junk".

In April S&P threatened that it could downgrade the country's sovereign rating to "below-investment" grade within 24 months.

A "junk status" would have implied a huge crisis on the external front.

In his speech, Mr Singh outlined its contours, saying it would lead to a higher fiscal deficit, and a further steep rise in prices.

He added that in such a situation "both domestic as well as foreign investors would be reluctant to invest in our economy", and Indian companies would not be able to borrow abroad.

Mr Singh was the finance minister during the 1991 crisis

The result: dismal economic growth and high unemployment.

Mr Singh said that the last time the country faced this problem was in 1991.

By June 1991, following the Gulf war, soaring global crude prices and domestic political uncertainty, India faced an acute shortage of foreign exchange.

A 2002 International Monetary Fund (IMF) paper, external, said the foreign reserves were nearly depleted.

With less than a billion dollars, India could finance only a few weeks of imports, and was on the verge of defaulting on its external payment obligations.

Earlier, the country had to airlift 67 tonnes (67000kg) of gold and pledge it overseas to raise crucial foreign exchange.

Only when the Congress Party's Narasimha Rao government came to power in 1991 with Mr Singh as the finance minister, did India devalue its currency, take a huge loan from the IMF, and announced wide-ranging reforms to put her on the right economic track.

This year there were enough signals that the Indian economic situation could return to the 1990-91 days.

'Preventive action'

S&P in its April report, suggested India needed to act immediately to find answers to its economic problems, which included low growth, high inflation, huge debt, a looming fiscal deficit and a lack of reforms.

By May, another rating firm, Fitch, was keeping a close eye on the developments in India.

During its meetings with S&P and Fitch in those months, government officials said that the country's future outlook was not as bad as was painted by these agencies.

They told S&P that several reform measures were in the offing; critical bills pending in parliament would be passed in its monsoon session throughout August and September, and new important bills, including land acquisition, would be introduced.

Attempts were made to convince Fitch that inflows from foreign investors were still robust, signalling there was global optimism about India.

There have been protests against the reforms

Unfortunately, by the second week of September, both these arguments sounded hollow.

, external; there was a complete logjam as opposition parties stalled both the houses because of opposition charges against the prime minister in a scandal involving allocation of coalfields to private companies.

In the first quarter of 2012-13 (April-June 2012), gross foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows were more than 50% lower than in the same period in the previous year.

The growing evidence before the government by mid-September was that S&P would have no option but to downgrade India, and much sooner than its two-year deadline.

Only this time, unlike in 1991 when he swallowed the reform pills as per the IMF prescription, the prime minister decided to act on S&P's suggestions, say experts.

In its April report, the rating agency had urged the government to raise diesel prices, cap subsidies on other fuels such as LPG, and remove FDI restrictions in sectors such as multi-brand retail and banking.

Most of these policies were announced by the government in September.

Mr Singh's justification for these measures was that "I know what happened in 1991 and I would be failing in my duty as prime minister of this great country if I did not take strong preventive action".

- Published21 September 2012

- Published20 September 2012

- Published14 September 2012

- Published20 September 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published19 September 2012

- Published17 September 2012