Is Rahul Gandhi reluctant to become PM?

- Published

- comments

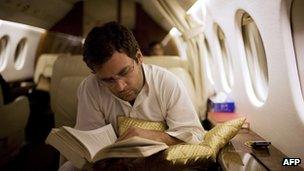

Rahul Gandhi has been called a reluctant politician

It is not the first time the heir apparent of India's powerful Nehru-Gandhi dynasty has spoken about his disinclination to become the prime minister in the event of his party winning the general elections.

"Asking me whether you want to be the prime minister is a wrong question," Rahul Gandhi of the ruling Congress party told MPs at an informal meeting on Tuesday. "The prime minister's post is not my priority. I believe in long-term politics."

He reiterated that his priorities lay in decentralising power, democratising the party, building local leaders. Nobody disagrees that the Congress direly needs all of this to energise its rank and file and improve its political prospects.

And then, if local reports are to be believed, he made a curious comment, external on his marriage prospects.

"If I get married and have children, I will be a status quoist and will be concerned about bequeathing my position to my children," he reportedly said.

The context of this remark is not clear, but in the past Mr Gandhi has publicly expressed his discomfort with dynastic politics, of which he himself is a privileged beneficiary.

His latest remarks seem to have baffled political watchers.

In January, he was promoted to the number two position in the party, becoming its vice president. (His mother, Sonia Gandhi, is the president.)

Many analysts - and party supporters - then said the 42-year-old leader's elevation was a step forward in nominating him as the party's candidate in the 2014 general elections.

Now he appears to be - again - sounding reluctant about becoming the prime minister.

Many believe Mr Gandhi's remarks on Tuesday may have been timed to counter a recent attack on Congress's dynastic politics, external by Narendra Modi who, many believe, is being positioned as the prime ministerial candidate by the main opposition Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

On the face of it, Mr Gandhi may be caught between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, it appears that he genuinely believes in democratising his party - political power and patronage in the Congress has traditionally flowed from the top, thus thwarting the organic growth of strong local leaders and weakening the party in key states like Uttar Pradesh. Mr Gandhi has said he believes in a more democratic politics and that merit should score over dynastic privilege.

On the other, his message may not be finding too many takers within his own party, where generations of leaders and workers have believed that there is no life beyond the Delhi dynasty. The raison d'etre of the Congress, they believe, is loyalty to the Gandhi family. It is what keeps the flock of leaders and workers together.

"The party is completely anchored in one family. Most of the leaders at the top and bottom have no bases of their own. All power flows from the high command. Local leaders are measured by what they can do for the high command and keep it in good humour," says Aarthi Ramachandran, author of Decoding Rahul Gandhi, external, a well-researched study of the man and his politics.

Mr Gandhi's dream reforms require him to remain in control and allow leaders to become powerful under his watch. Will he able to strike that balance? It requires astute political thinking and management. Does he possess that? Only time will tell.

In the end, however, Mr Gandhi may even be a bit ahead of the curve. Indian voters actually still do not seem to have a problem with dynastic politics.

As analyst and editor of The Indian Express newspaper Shekhar Gupta pointed out recently, there are at least 15 new politically significant dynasties, external which are thriving in key states like Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Orissa.

"Each one of these now has a strong, proprietary vote bank and total ownership of its party. A pan-national [Gandhi-Nehru] dynasty no longer has the ability to breach these fortresses," he says.

So is it strictly a problem of opaque dynastic politics that is impeding the growth of Congress? Or is it, as many argue, an inability to tap into the political zeitgeist and face up to the reality that building powerful local leaders and tapping into regional issues are key to its national electoral fortunes?