Does the Delhi gang rape sentence bring closure?

- Published

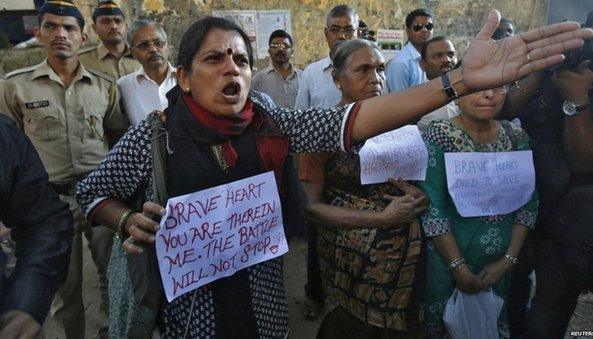

Protesters said the attack has highlighted the poor social and economic conditions many Indian women suffer

Did the fatal gang rape of a student last December eventually turn out to be a moment of dramatic change for India? And does the court's decision on Friday to hand out the death penalty to the four guilty men mark some kind of a closure?

The answer to the first question is possibly yes. The answer to the second is arguably, no.

The horrific crime triggered a firestorm of protest in the country like no other incident in the recent past. It touched a chord largely because India's restless and increasingly assertive youth - a fifth of India's 725 million eligible voters next year will be between 18 and 23 years old - identified with the victim: a struggling aspirant whose life came to a brutal end on the way back home after watching a film with her friend at a multiplex cinema in one of Delhi's ritzy shopping malls. A strident and purposeful media helped deepen this rage.

Over time the rage led to what many say is a deeper engagement with issues relating to violence against and discrimination of women. The young have taken the lead: schools, colleges and youth communities are agog with informed debate. As novelist Nilanjana Roy eloquently puts it: "The rapes might not stop; but this conversation isn't stopping either."

The Delhi rape also shone a light on poor, deracinated migrants who flock to the cities to escape the grinding poverty of their villages. As Jason Burke explains in this brilliant piece of reportage, external, the four men who raped the student represented a bulk of today's Indians - semi-skilled, poorly educated, unmarried and high on cheap alcohol in a city which has an awful sex ratio and record of protecting women and "high levels of alcohol abuse."

Also, the government, initially slow to respond to the chorus of outrage, was pushed to implement tougher anti-rape laws, which in itself was a positive development.

After the self-flagellation and scathing international condemnation - many said India had become the world's rape capital - there is an increasing realisation that rape is a deeply complex problem and blights all countries. Especially in India where the the majority of perpetrators are family members, relatives and friends of the victims. This useful infographic, external offers some clues: five cities in Madhya Pradesh, one of India's most undeveloped states which fares poorly in feeding, educating and protecting its women, have the highest rates of rape, but so do the prosperous cities of Delhi and Mumbai.

But India is not alone. Last week I read of college students in the US being disciplined after they were seen apparently "extolling the joys of sexual assault", external on an Instagram video. And a recent piece in the New Yorker revisited an incident in Steubenville, Ohio where high school football players were accused of repeatedly raping an unconscious 16-year-old girl after she was ferried from one party to another, that had earlier provoked a comment in New York Times titled Is Delhi So Different From Steubenville, external?

Nevertheless, there were nearly 25,000 reported cases in 2012 in India. In Delhi alone, over 1,000 cases of rape were reported until mid-August this year, against 433 cases reported over the same period last year. In dirt-poor Jharkhand, over 800 cases have been reported in the past seven months, up from 460 in the whole of 2012. The increase in numbers could be because of increased reporting by the victims, which in itself is a good thing. But the fact is that the violence continues unabated.

Clearly, patriarchy, misogyny and blaming women for "provoking" men are only part of the problem. India's criminal justice system remains broke: too few judges and policemen, shoddy investigations, questionable trials, low conviction rates.

More importantly, India, many say, needs to consider why in a society which, justly, prides itself on strong family values, continues to tolerate what many say is widespread abuse of and violence against women at home. There is simply not enough debate on this. "We are argumentative about everything except our own selves," writes sociologist Sanjay Srivastava in this excellent piece, external. Why are people talking without listening?

India also needs to become a more equitable society where fewer people will be left angry, frustrated and marooned in poverty amid shiny islands of wealth. Poverty, inequality and violence are inextricably linked.