Can India really provide bank accounts to 1.2 billion people?

- Published

Nearly 40% of Indians have little or no access to formal banking services

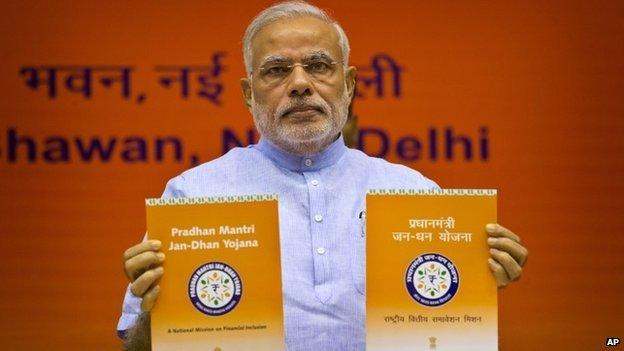

When it comes to ambition, one cannot find fault with India's new Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

His recent pledge to provide bank accounts to all of his country's 1.2 billion people - and in particular its poorest citizens - is one of the most audacious ever announced by an Indian government.

It is ambitious because nearly 40% of Indians, or some 480 million people, have little or no access to financial services.

To put that in context, that is nearly one-and-a-half times the US population and nearly 17% of world's entire "unbanked" population.

Even if the task at hand is difficult, it does not mean it is not a worthy goal.

As more people - especially the poor - gain access to financial services, they will be able to save better and get access to funding in a more structured manner.

This will reduce income inequality, help the poor up the ladder, and contribute to economic development.

But there are many hurdles India will need to overcome before its plan can make a significant impact.

The infrastructure barrier

The first is changing the mindset of what a bank "looks" like. And this will have to happen at all levels, from government to consumers to the banks themselves.

A nationwide network of typical brick-and-mortar branches is simply not a feasible option, from a timeline or profit standpoint. The government needs to realise this fast. At present, it is issuing licenses for new banks with a condition that 25% of the branches will be opened in rural areas.

On 15 August, PM Narendra Modi pledged to provide bank accounts to all of India's 1.2 billion people

This may not a workable idea on many fronts, not least because of the lack of trained staff to work at these branches.

At the same time, the amount of profit and revenue that the branches in rural areas would generate may not justify the expenses.

As a result, banks must adapt their business models.

One way to do this is to tap into mobile banking, using the more than 900 million mobile phones in use in India.

Another is by using the ubiquitous mom-and-pop stores as channels for collecting and distributing funds, especially in rural areas, with simple cards to track money flows.

These shops provide great local access, as their customers tend to be regulars who have built a relationship of mutual trust with the owners.

Mann Deshi Mahila Bank in India, a co-operative bank, has used e-card technology to take its services to rural women. These e-cards instantly allow the bank's field agents and clients to view savings account balance, loan account status, and repayment history.

Red carpet or red tape

On his recent visit to Japan, Mr Modi declared that India was replacing its infamous "red tape" culture with a "red carpet" mindset. The comment was aimed at attracting more foreign investors to India. His ambitious domestic banking plan could do with a similar change in attitude.

A key aspect to expanding the reach of the financial services to more people will be simplifying the regulatory environment around it.

The government aims to provide bank accounts to 75 million households by 2018

To begin with, customer documentation - currently a byzantine process requiring many forms of proof - must be simple enough so that people, especially those who have never been to a bank, won't be scared off.

State-owned banks currently dominate India's banking sector and they will be key to making Mr Modi's plan a success.

However, they have long been averse to offering accounts to people with little money because of costs and low profits. The government has to make it easier and more lucrative for these lenders to operate in these areas.

Financial literacy

The unbanked in rural areas must adapt to the idea of banking and believe it is worth their time. The key to this is increasing financial literacy. Most of the target people are unlikely to have much knowledge about how they can use banking services to their benefit.

The government and banks have to take the lead in educating people about how they can use these services - savings or loans - to create wealth.

Cash is costly to print, move, secure, and store

One aim of the plan is to help the government pay rural poor their welfare benefits directly into accounts, cutting layers of corruption. This is an area where banks can tap into and create tailor-made products and services for customers to help them utilise these benefits better.

The banks can also reach out to these customers with more personalised help. For example, if farmers from a certain village are supplying milk to a dairy plant, the bank can use the plant's accounting team to inform and educate farmers about how they can save money or get loans for buying new cattle.

The success of such an ambitious plan hinges on a holistic approach and multiple stakeholders playing a part, not just government policy.

Cashless future?

While we are talking about big ambitions, one major step could help this plan succeed: cutting India's dependence on cash.

Cash is costly to print, move, secure, and store, yet it is basically free to users. Mobile and technology-enabled payments, on the other hand, can prove cheaper and more beneficial for the economic system including for the government, retailers, telecom operators and the banks.

It is crucial to increase financial literacy, especially in rural areas

It won't be easy to change this, but a combined effort by the various stakeholders can help build an electronic payment system. Not only would that reduce the costs of making banking more accessible in rural areas, it will also help India address the country's many unaccounted cash transactions and the parallel underground economy.

Reaching 1.2 billion people may prove impossible in the long run - no developed country has achieved 100% banking so far. But if India can work towards addressing these challenges, financial inclusion in the country could increase significantly.

That can only be good news for Asia's third-largest economy.

Jungkiu Choi, a former banker, is Partner, Financial Institutions Practice, with global management consulting firm AT Kearney

- Published28 August 2014

- Published28 August 2014

- Published2 September 2014

- Published21 December 2010

- Published16 December 2010

- Published28 February 2013

- Published4 August 2014

- Published31 January 2014