Why Obama's India Republic Day visit is significant

- Published

This is the first time that a US head of state is the chief guest at India's Republic Day celebrations

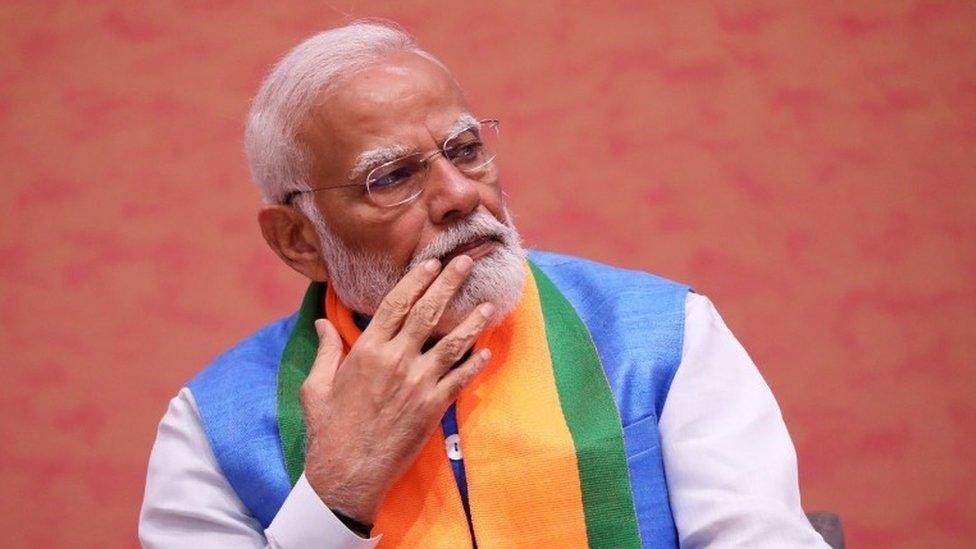

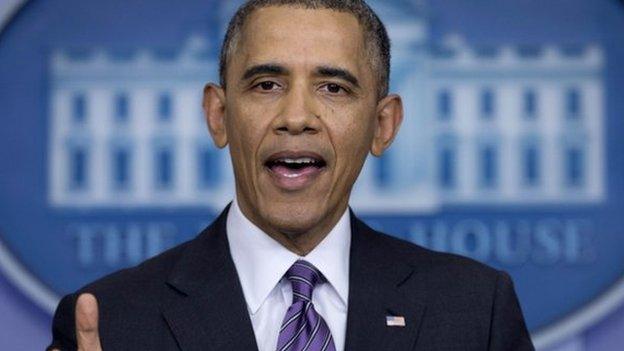

The most significant aspect of the US President, Barack Obama's upcoming summit with the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, is that Mr Obama will be the chief guest at India's Republic Day celebrations.

This is the first time that a US head of state will be given this honour by India and reflects, more than anything else, the degree of comfort that Delhi has in its relations with Washington.

India, traditionally, has invited its Republic Day guests who will not attract controversy at home and come from countries with whom it has close strategic relations.

Thus the heads of neither Pakistan nor China have been invited on the first count. While no Latin American leaders have ever come for the second reason.

It says something about how difficult Indo-US relations have been that it has taken over seven decades for Delhi to invite the US president to participate in a ceremony marking its emergence as a full-fledged constitutional democracy.

While there is much focus on what diplomats call the "deliverables" - substantive agreements and deals - that will emerge from the meeting, the likelihood is that the symbolism will be much greater than the substance on this visit.

Mr Obama and Mr Modi held a fruitful summit in September last year and the present invitation was extended seemingly on the spur of the moment by Mr Modi when the two met on sidelines of the East Asia Summit in Myanmar (Burma) last November.

This has meant, officials on both sides admit, relatively little time to put together a substantial agenda.

A better measure of the Republic Day summit's agenda will be the areas the bilateral talks will focus on - defence, energy and counter-terrorism.

These are all in the sensitive zone of most governments and the depth of the discussion in each of these underlines how close the two countries have become.

Contending interests

In defence, the spearhead of the relationship is less the business of selling and buying arms than attempts by India and the US to jointly develop and produce a new generation of weaponry.

This idea has been kicked around for several years between the two countries, struggling to overcome political and bureaucratic resistance within both capitals.

The expectation is that at least one, if not more, such deals will be signed later this month.

A few dozen possible technologies and weapon systems have been offered by the US.

India is particularly interested in drones, carrier technology and so on that enhance its ability to project its air and naval power.

In energy, the two governments are looking at contending interests - improving the supply of fossil fuels and inhibiting climate change.

Mr Modi and Mr Obama are relatively unusual among world leaders in their personal belief that global warming is an issue of overriding importance.

The US has thus been a strong supporter - though with some commercial opportunities in mind - of the Indian government's ambitious plans for renewable energy, especially solar. The September Indo-US summit was shot through with green energy.

India's Republic Day celebration is a spectacular event

Mr Obama would like Mr Modi to give binding commitments on India's carbon emissions, even ones as broad as the ones China agreed to recently.

But India has a troubled fossil fuel dependent power generation sector. It is looking increasingly to the US for inexpensive natural gas - and has been pushing for a long-term commitment by Washington to allow such imports.

The US, in return, will continue to push India to change a flawed nuclear liability law that makes it difficult for the US and other countries to sell reactors to an energy-starved India.

Neither issue is likely to be resolved during this summit, though there may be discussion to that effect.

Intelligence sharing

Counter-terrorism is a particularly good measure of the strength of relations for two reasons.

One, India continues to be wary of the degree of intelligence cooperation between the US to India's regional rival, Pakistan. The more Indian and US intelligence agencies work together, the less important the shadow of Pakistan becomes to bilateral relations.

By all accounts, India and US already enjoy a very high level of intelligence sharing on terrorism.

Narendra Modi visited the US in September

Notably, when European governments were complaining about revelations of widespread electronic surveillance by the US National Security Agency, a terrorism-wary India reportedly asked the NSA to step up its eavesdropping activities.

An area where the two sides are working more closely together, however, is cybersecurity.

An ever more connected India is becoming more conscious of its vulnerabilities in this area and understands the need for international support.

However, the spectacle that will accompany the Republic Day summit will obscure the weakness of shared big strategic thinking between the two countries.

The two leaders are extremely focused on domestic concerns, seeing foreign policy as a sideshow to the economic and social agenda they have for their own countries.

The two are on opposite sides when it comes to the US policies in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

But they are increasingly on the same page when it comes to East Asia and China.

When Mr Obama takes the salute of marching Indian soldiers, these will not be at the forefront of the summit agenda.

The symbolism of the event will undermine the other side of the geopolitical coin: differences between India and the US pale in comparison to what brings them together.

Pramit Pal Chaudhuri is Foreign Editor of Hindustan Times

- Published25 September 2014

- Published23 April 2024

- Published24 November 2014

- Published27 September 2014