Raman Raghav: When India's 'Jack the Ripper' terrorised Mumbai

- Published

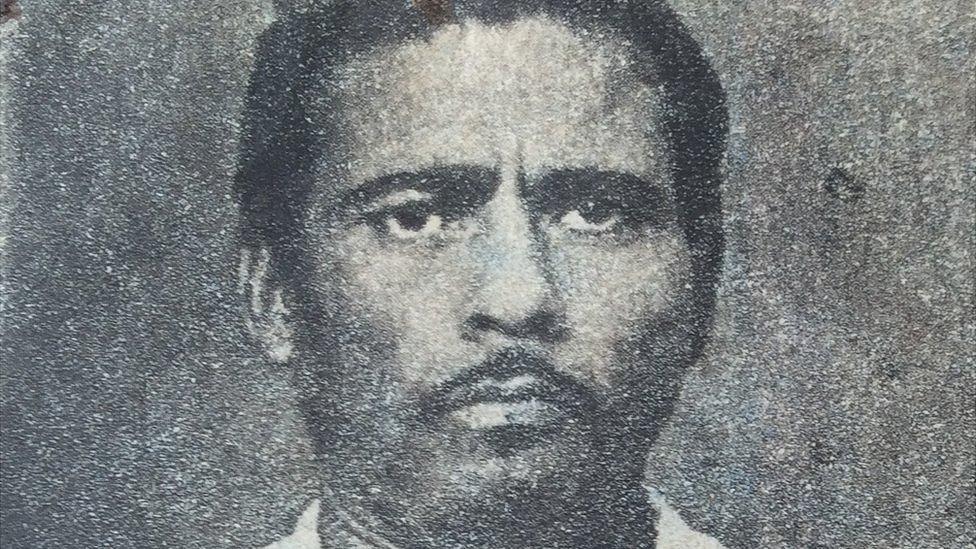

Raman Raghav confessed to murdering 41 people

Nearly 50 years after Raman Raghav terrorised Mumbai (then Bombay) by murdering 41 people, there's renewed interest in the serial killer - a film made for television in 1991 had its first public screening a fortnight ago and Raghav is also the subject of a feature film being made by indie director Anurag Kashyap.

The BBC's Geeta Pandey travels to Mumbai to piece together the story of the man described as India's "Jack the Ripper".

Raman Raghav went on a killing spree over three years in the 1960s, casting a spell of fear over the city.

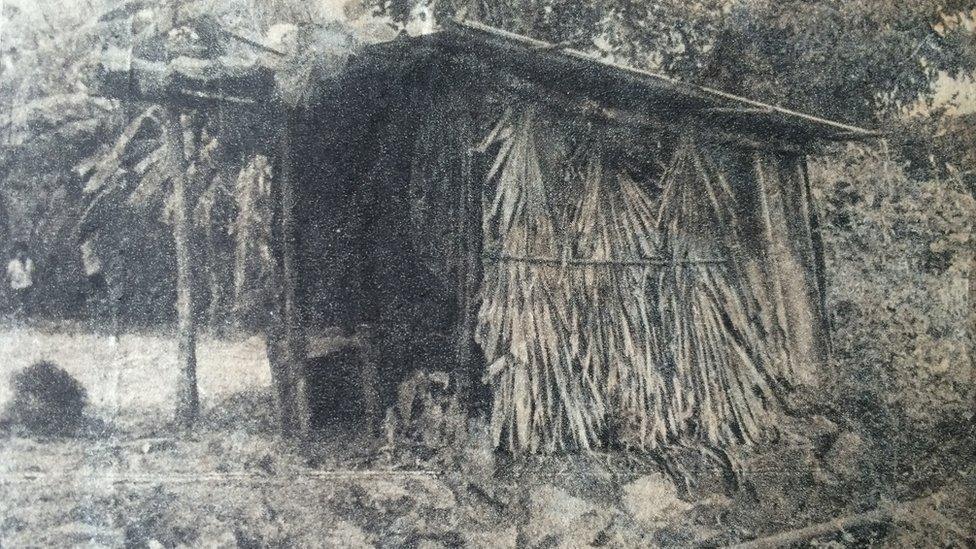

His victims were all poor people who either slept on the pavements or lived in ramshackle huts and temporary shanties in the northern suburbs of the city. They included men, women and children - even infants.

They were attacked at night while they slept, and all of them died after their heads were smashed with "a hard and blunt instrument", writes Ramakant Kulkarni, the young police officer who took over as the head of the crime branch in 1968 and whose team eventually captured Raghav on 27 August 1968.

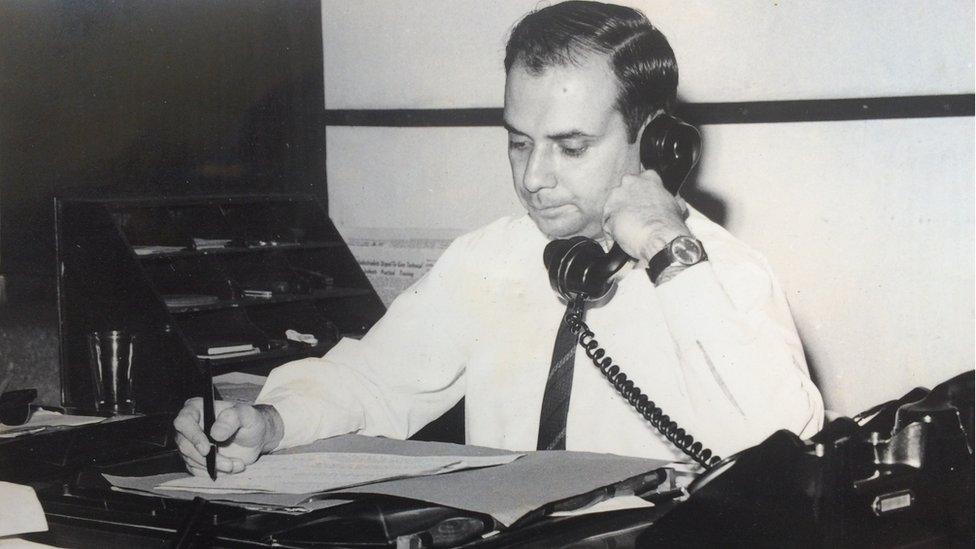

When Ramakant Kulkarni took over as the head of the crime branch, many said he was too young to investigate such a sensitive case

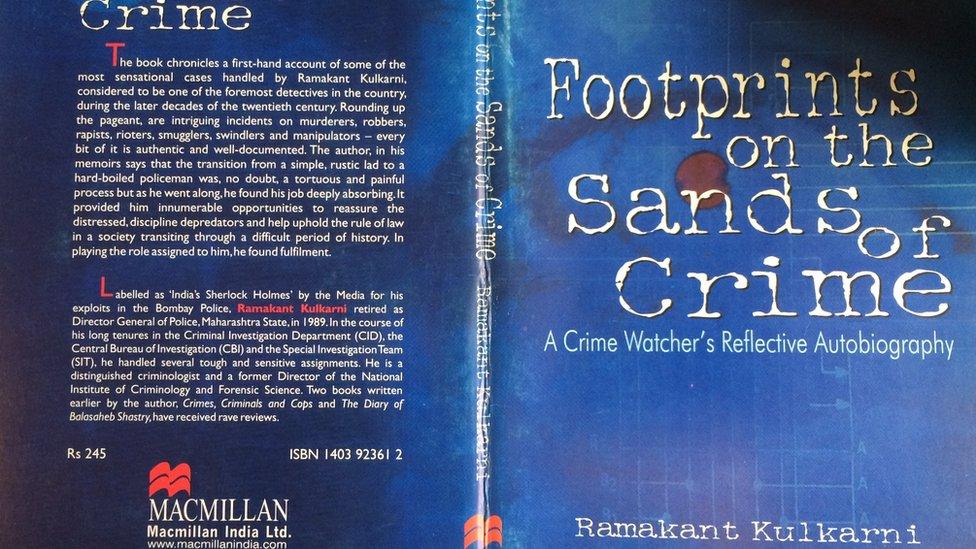

Mr Kulkarni, who retired in 1990 as the head of Maharashtra police and died in 2005, wrote detailed accounts of the case in two books: "Footprints on the Sands of Crimes" and "Crimes, Criminals and Cops".

"The murders were motiveless... if any petty gain had been achieved in the process, the violence inflicted on the victims was totally disproportionate to any such gain," he wrote.

As new murders were reported almost daily, rumours began circulating about "a mysterious assailant... gifted with supernatural powers" who could "assume the shape of a parrot or a cat" and the press dubbed him "India's Jack the Ripper", according to Lily Kulkarni, Mr Kulkarni's wife.

More than 2,000 policemen patrolled the streets at the time, but the city was in the grip of panic, especially in the suburban areas, Mrs Kulkarni says.

For all his murders, Raghav used an iron rod, shaped like the number 7

Parks and streets emptied out at dusk and in many areas, nervous residents carrying sticks patrolled the streets.

There were several incidents in which beggars and homeless men were badly assaulted by panicky crowds.

The murders took place in two lots - the first between 1965 and 1966 when 19 people were attacked. Raghav, who was found loitering in the area, was picked up then as well, but let off because police couldn't find any evidence against him.

The second round of killings took place in 1968, and on 27 August, a sub-inspector from Mr Kulkarni's team recognised him from photographs and descriptions given by those who had survived his attacks.

Most of his victims lived in ramshackle huts which he could enter easily, like the one in this photo in which he murdered an elderly priest

"As the news of the arrest spread, a large crowd gathered outside my husband's office. People celebrated," Mrs Kulkarni remembers.

There is little known about Raghav's childhood or early life. Reports from the time describe him as a Tamilian, who was tall and well-built, had little school education and was homeless.

During interrogation, he proved to be "a tough nut" who refused to say anything for two days, but the police had a breakthrough on day three.

Mrs Kulkarni says the murders had the city in the grip of a panic

Mr Kulkarni's book describes how one of Raghav's interrogators casually asked him if there was something which he really wanted and "without a moment's thought", he said "murgi" - chicken.

After he was fed a dish of chicken, he was asked if he wanted something else.

He asked for more chicken.

Next, he said he would "like to have a prostitute, but I guess the law does not permit that while one is in custody" - so he settled for hair oil, a comb and a mirror instead.

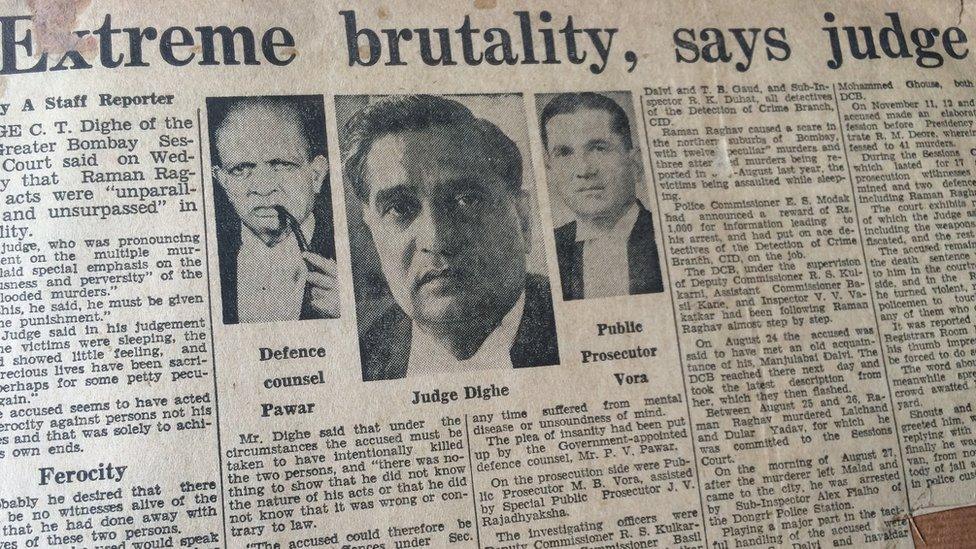

The case made daily headlines in newspapers

"He massaged his whole body with the coconut oil, appreciating its fragrance, combed his hair and looked admiringly at his own face in the mirror."

Then, he asked the police what they wanted from him.

"We want to know about the murders," one officer said.

"Well I shall tell you all about them," he said, and led the policemen to the bushes in Aarey Colony where he had hidden his tools - an iron crowbar, knives and other weapons.

During his confession before the magistrate, Raghav admitted to killing 41 people, though police say they believe the numbers to be higher.

In his confession, he said he had done it voluntarily and that he had been instructed by "God" to do so.

Other Indian serial killers

Surinder Koli has been found guilty of five murders and is on death row

'Auto' Shankar: Convicted of killing six people in the late 1980s in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. His real name was Gowri Shankar, but he was called Auto Shankar because he drove an autorickshaw. He and his group were found guilty of transporting illicit liquor, abducting women and running a prostitution racket, besides brutal murders. He was hanged in 1995.

'Cyanide' Mohan: Convicted in the southern state of Karnataka of killing 20 women. Born in 1963, Mohan Kumar preyed on women looking to get married - he would give them cyanide pills claiming they were contraceptives and rob them of their jewellery. He was arrested in 2009 and given the death sentence in December 2013.

Surinder Koli: Worked as the servant for businessman Moninder Singh Pandher in Nithari village in the Delhi suburb of Noida. The servant and the master were accused of killing, raping and dismembering at least 19 young women and children. Koli was accused even of cannibalism. The deaths were discovered in December 2006 after body parts and children's clothing were found blocking the sewer running in front of the house. While Mr Pandher was later freed on bail for lack of evidence, Koli has been found guilty of five murders. He is on death row.

The Stoneman: Nine people were killed in Mumbai in 1989 and each victim was found with their head bludgeoned by a stone or a heavy blunt object. The case remains one of the most famous unsolved murders in India as the killer was never caught.

The Beerman: Six people were killed in Mumbai between October 2006 and January 2007 and in each case, a bottle of beer was found beside the body. Police arrested Ravindra Kantrole and accused him of being the Beerman, but he was freed due to lack of evidence.

During his trial, Raghav's lawyers pleaded insanity - they said he did not know that killing people "was wrong or contrary to law".

But the "police surgeon" certified him as "neither suffering from psychosis nor mentally retarded", and the court gave him the death penalty.

In his order, Judge CT Dighe described him as a "psychopath, extremely wicked man with depraved or brutal mentality" and said his crimes were "unparalleled and unsurpassed in brutality".

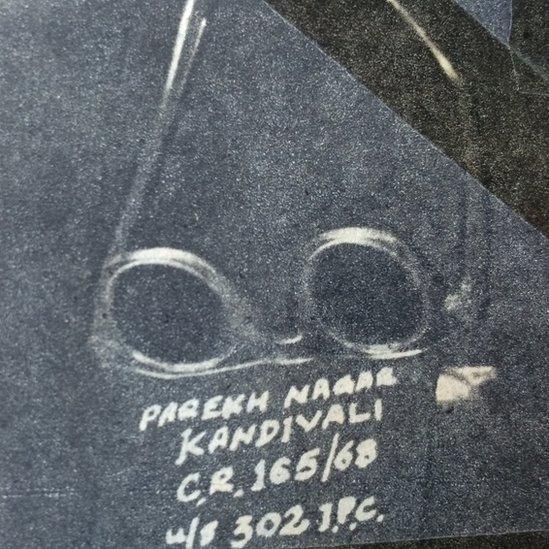

Among the items Raghav stole from his victims were a pair of old reading glasses, an old umbrella, a cooking stove, an old wristwatch and a jar

Media reports at the time said a large crowd outside the court greeted Raghav with "shouts, whistles and jeers" - and he "replied with equal energy".

Despite the ruthlessness of his crimes, and the fact that Raghav did not appeal, he escaped the gallows.

The high court, which had to confirm his death sentence, ordered a re-evaluation of his sanity and put his sentence on hold after a panel of three psychiatrists said he was schizophrenic and suffered from delusions and hence was "incurably mentally ill".

"We got lots of calls from the public, mostly women, asking my husband why he was not being hanged," Mrs Kulkarni said.

Raghav was lodged in Yerwada jail in the city of Pune.

Police officer Ramakant Kulkarni wrote about the case in two books

In 1987, after he had spent 18 years in solitary confinement, the high court commuted his death sentence to life in jail, and he died from a kidney ailment the same year.

Today, nearly 50 years later, not many in Mumbai know about Raman Raghav.

Perhaps the two films will help revive the interest in the psychopath who once terrorised the city.