How 'black money' saved the Indian economy

- Published

There is no question that India has the most positive economic story on the planet.

Buoyed by increased manufacturing output, India's economy grew by 7.4% in the third quarter of 2015, the fastest growth of any major country in the world.

But there is a dark side to India's success, says one of the country's most eminent economists.

Kaushik Basu, the chief economist of the World Bank and former chief economic adviser to the Indian government, says the nation's tradition of petty corruption helped India avoid the worst of the banking crisis that has crippled most other large economies in the last few years.

It is an extraordinary claim for such an influential figure to make but, as he says in his new book, external, An Economist in the Real World, "economics is not a moral subject".

His argument is that the pervasive use of "black money" - illegal cash, hidden from the tax authorities - created a bulwark against a crisis in the banking sector.

Let me explain.

Mr Basu says dirty money saved India from the financial crisis that engulfed the rest of the world

Back in the last years of the noughties India's economy was looking just as frothy as the rest of the world.

It had been growing at an astounding 9% a year for the three years to 2008.

What's more, India's growth had been fuelled, at least in part, by a dramatic housing boom.

Between 2002 and 2006 average property prices increased by 16% a year, way ahead of average incomes, and faster even than in the US.

The difference in India is that all this "irrational exuberance" did not end in disaster.

Dirty money

There was no subprime loans crisis to precipitate a wider crisis throughout the banking sector.

So the big question is why not.

There were some shrewd precautionary moves by India's central bank, concedes Mr Basu, but he says one important answer is all that dirty money.

In most of the world the price you pay for a property is pretty much the price listed in the window of the local realtor or estate agent.

Not in India.

Here a significant part of almost all house purchases are made in cash.

And because the highest denomination note in India is 1,000 rupees, ($15; £10) it isn't unusual for a buyer to turn up with - literally - a suitcase full of used notes.

This is how it works.

Let's say you like the look of a house that is for sale. You judge it is worth - for argument's sake - 100 rupees.

The chances are the seller will tell you he will only take, say, 50 rupees as a formal payment and demand the rest in cash.

That cash payment is what Indians refer to as "black money".

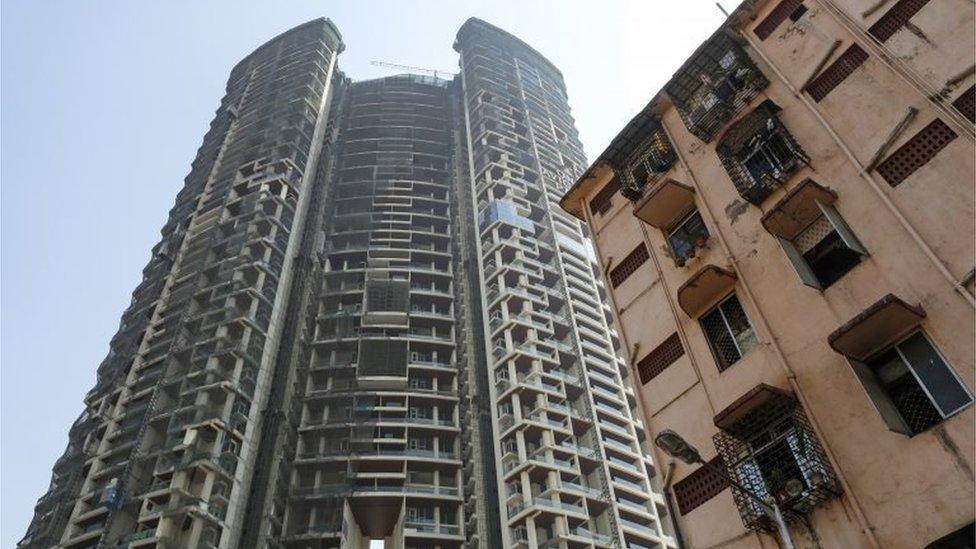

Homebuyers will almost always have to pay part of the property price in cash

It means the seller can avoid a hefty capital gains tax bill. Buyers benefit too because the lower the declared value of the property, the lower the property tax they will be obliged to pay.

What it also means is that Indians tend to have much smaller mortgages compared to the real value of their properties than elsewhere in the world.

At the peak of the property boom in the US and the UK it was common for lenders to offer mortgages worth 100% of the value of the property.

Some would even offer 110% mortgages, allowing buyers to roll in the cost of finance and furnishing their new home.

That's why when the crash came, the balance sheets of the big banks collapsed along with property prices.

In India, by contrast, mortgage loans can only be raised on the formal house price. So, says Mr Basu, a house worth 100 rupees would typically be bought with a mortgage of 50 rupees or less.

So when prices fell in India - and they did fall in 2008 and 2009 - most bank loans were still comfortably within the value of the property.

That's why India managed to avoid the subprime crisis that did so much damage elsewhere.

Legalising bribery

India did experience a slowdown, but it was collateral damage from the global recession rather than the result of any national problem. Indeed, within a year India had begun to pull out of the crisis, returning to growth of almost 8% a year between 2009 and 2011.

That is not to say that Mr Basu approves of petty corruption.

Mr Basu says only those who take bribes should be held criminally responsible

He compares it to the effect of an unpleasant disease: it may have some positive side effects - encouraging your hair to grow, for example - but you would still prefer not to have the illness.

Indeed, Mr Basu is famous for having devised a particularly clever and characteristically radical way of rooting out corruption - legalising bribery.

A few years ago, he proposed that instead of both bribe-givers and bribe-takers being held criminally responsible for their actions, only the bribe-taker should face sanctions.

It is a simple change, but radically alters the relationship between the two parties.

It means people who give bribes no longer have a shared interest in keeping their nefarious activity secret.

Freed from the risk of prosecution, bribe-givers would have a powerful incentive to reveal corruption.

Unfortunately, says Mr Basu, his innovation has still not found its way into mainstream Indian law.

- Published29 October 2014

- Published23 June 2014