How an Indian writer 'returned from the dead'

- Published

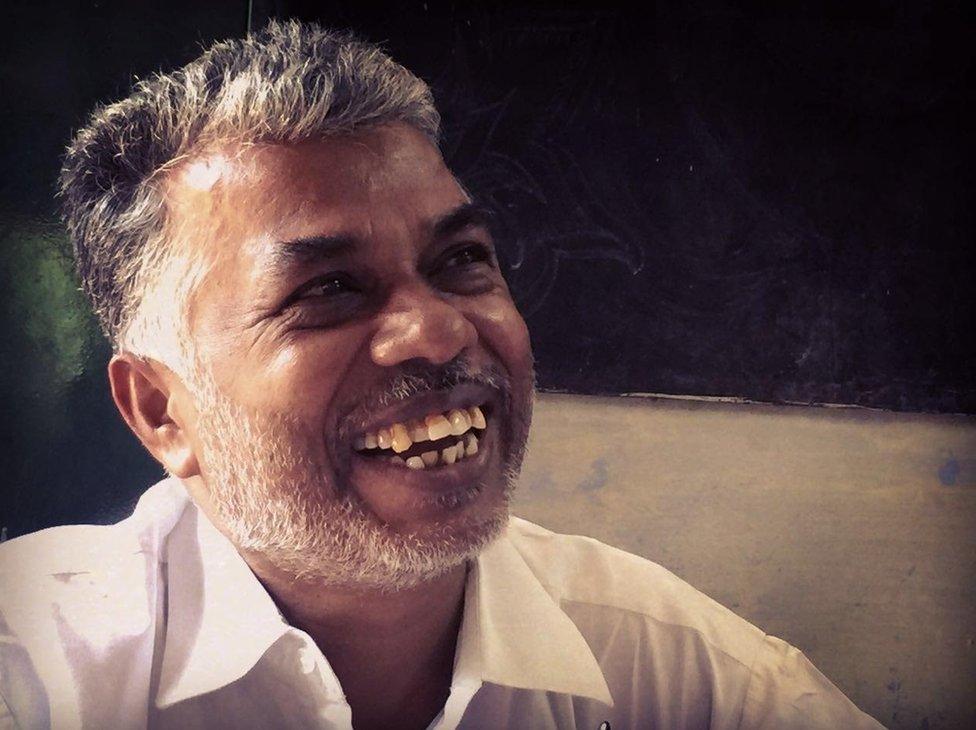

Perumal Murugan is seen as one of the finest writers in the Tamil language

For months after Perumal Murugan declared himself "dead", external as a writer following vicious protests against his novel by Hindu and caste-based groups last year, he couldn't read or write.

"I became a walking corpse," says Murugan, who is considered to be one of the most accomplished writers , externalin the Tamil language.

Then something happened. Murugan went to see his daughter in the temple town of Madurai, and spent a few days in a friend's house. There were two rooms on the first floor: one stacked with books, and the other had a bed.

"With nothing to do I lay dazed night and day," he told a gathering in Delhi on Monday evening.

"I wallowed in a dark hole without the urge to see or talk to anybody. But as I ruminated over my existence, there came a certain instant when the sluice gates were breached.

"I began to write."

Saviour

Murugan says he wrote whenever anything struck him.

"As I started to write, I began to revive little by little, from my finger nails to my hair."

He began writing poems. After all, his first piece of writing when he was "eight or nine" was a ditty on a pet cat. Although he later became famous for his novels and short stories, poetry had always been his first love. Not many know that he has four published volumes of poetry. Poems come easily to him: his third novel, for example, took him seven years to write, but he never stopped writing poetry.

Poetry has now saved him again.

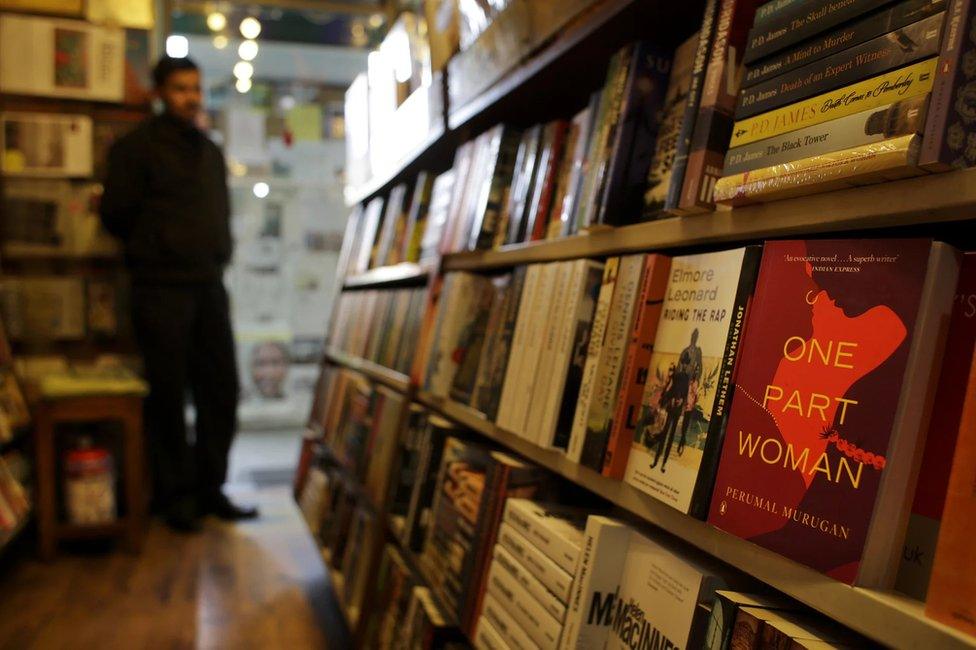

Copies of his novel were burnt and a petition sought the arrest of the author

In July, a court threw out a slew of petitions demanding that Murugan be prosecuted for his writings.

"Let the author be resurrected to what he is best at: write," said the judges.

Murugan says the judges' "order" sounded both like a "command and a benediction".

Earlier this week, Murugan, 50, returned with a collection of 200 poems he had written in exile.

It is called Oru Kozhaiyin Paadalkal - A Coward's Song - many of the poems are dark and brooding, possibly reflecting his state of mind during his exile.

One of them goes:

All that is left/is to die, flesh torn/and ravaged, like a chicken/caught among crows.

I ask for nothing, sir/let me just live by the side/as a spectator/as a mere spectator.

"A writer has returned to life," rhapsodised well-known Hindi poet Ashok Vajpeyi. "His new poems are full of courage and imagination".

Wounds of exile

But the wounds of a painful exile haven't healed.

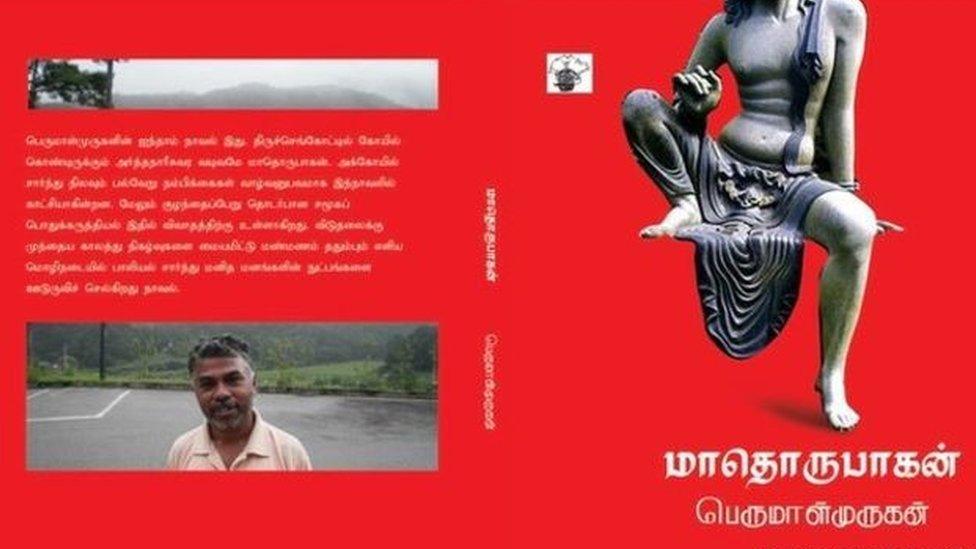

His novel Madhorubhagan (One Part Woman) that whipped up a storm is a gripping fictional account of a poor, childless couple, and how the wife, who wants to conceive, takes part in an ancient Hindu chariot festival where, on one night, consensual sex between any man and woman is allowed.

Set about a century ago near the author's home town of Tiruchengode in southern India, Murugan explores the tyranny of caste and pathologies of a community in tearing the couple apart and destroying their marriage.

Murugan's novel kicked up a storm in his native state of Tamil Nadu

Local groups led protests against the book, saying the "fictitious" extramarital sex ritual at the centre of the plot insulted the town, its temple and its women. Copies of the novel were burnt, residents shut down shops and a petition sought the arrest of the author.

Now Murugan, a quiet and self-effacing man who is evidently uncomfortable with the limelight, says a "censor is seated inside me now".

"He is testing every word that is born within me. His constant caution that a word may be misunderstood so, or it may be interpreted thus, is a real bother. But I'm unable to shake him off. If this is wrong let the Indian intellectual world forgive me."

'Weary task'

The author of five novels who has spent 17 years as a teacher of Tamil says he is even mulling over the re-publication of his earlier writings: he will soon "begin the weary task of reviewing my books" and if required, "I will revise the text".

"I'm not sure if this is right. However, when so many things that are not quite right are happening all over, why not this? What am I to do?"

Rooted in the western region of Tamil Nadu where he was born, Murugan's stories are peopled by characters caught up in change, struggling peasants, a child bonded to work in an upper caste home to repay the loan taken by his father.

He is outspoken about the evil practice of caste discrimination which, he says, "is ubiquitous and subtly present at the same time". His writing, according to his translator Aniruddhan Vasudevan, is filled with "rich details of life, landscape, ecology and social life of a region".

Murugan has written five novels

Writer reborn?

"I come from a peasant family," Murugan says. "At the age of 20, I saw a house as a place to live. Before that I had lived in the open and in cow sheds.

"I have an undying passion for open spaces to this day. So my descriptions of landscape come from this experience."

So will Murugan be now reborn as a different author?

"There's a conflict in my mind. Most of my writings have been in the realist mode. I doubt whether I will write in that mode again. I may resort to other techniques [of story telling]. Only time will tell."

When Murugan quit writing last year, he said he would not resurrect himself. He has. He once told his children that he would love to write 15 books, of which 10 would be novels. Now, he promises to speak again, through his words.