'No customers': Indians react to currency ban

- Published

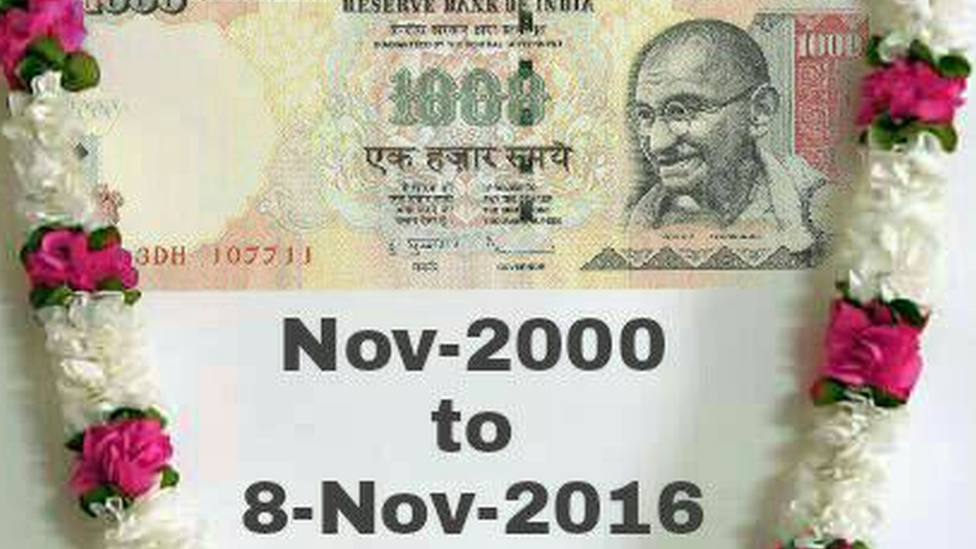

Old 500 and 1,000 rupee notes are no longer in circulation

Indians are scrambling to adjust to life without 500 and 1,000 rupee notes after they were removed from public circulation in a shock announcement on Tuesday night. The move is part of a crackdown on corruption and illegal cash holdings.

The BBC's Vikas Pandey in Delhi and Aakriti Thapar in Mumbai take to the streets to find out how citizens are coping.

'My child has cancer, we can't buy food'

Mohit Kumar, 10, has blood cancer

Mahavir Singh, sitting outside Delhi's famed All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), is the picture of despair. The farm labourer has travelled nearly 80km (49 miles) from his village with his mother and his 10-year-old son Mohit Kumar, who suffers from blood cancer. The trio had brought 5,000 rupees for the trip to cover food, travel and lodging expenses, only to find that most of their money is now effectively worthless.

"We are facing major problems. Auto-rickshaw drivers and hotels are not accepting 500 rupee notes and that is all I have. It's been such a struggle to feed my family, and my son will have to sleep on the pavement tonight," he told the BBC.

His mother, Pushpa Devi, says they have already spent all the 100 rupee notes they have. "I have heard that there are some people who come here every evening to distribute food as charity, so I am hoping we can have that for dinner."

'I have no customers'

Sameer owns a roadside clothing store

Sameer, who owns a roadside clothes shop along Mumbai's busy Linking road, says that he has had next to no customers all day.

"You can see, there is no one here," he says. "Those who do come in try purchasing a cheap item with their 500 and 1,000 rupee notes and then asking us for change since the ATMs are shut. But we are not accepting those notes.

"In the long run this is going to affect our business badly as we only deal in cash."

'You tell me what to do with this cash'

Kalamuddin works as a rickshaw puller in old Delhi

Kalamuddin, a rickshaw puller in old Delhi, is angry. "I am left with all this," he says, animatedly waving 500 rupee notes around. "What will I do? I don't have any identity card or even a bank account. It's my hard-earned money. You tell me how I can prove that this is not black money."

Mr Kalamuddin's problem is likely to be a common one in India, which is overwhelmingly a cash economy and where many daily-wage labourers do not possess formal identification or bank accounts.

'A great move'

Ranchor owns a convenience store in Mumbai

Ranchor, who owns a convenience store in western Mumbai, says he is accepting 500 and 1,000 rupee notes from customers desperate to rid themselves of the now-banned currency.

"But we are not giving any change back. They have to purchase goods that are worth that amount. We will go to the bank and change those notes.

"This has benefited us because people are coming here as they can't go to the smaller local shops. This is a great move by the prime minister. It is time to crack down on black money."

Wedding woes

Neeraj Bharadwaj runs a jewellery shop in old Delhi

Neeraj Bharadwaj, a jeweller in old Delhi, agrees it is important to bring "black money" back into the economy. But he says he is not sure about the way it was done.

"What are we going to do for the next few weeks? Our business is mainly during the wedding season, which starts in a few days. But now how are people going to buy gold and silver? They can only convert 4,000 rupees a day and that's not enough when you have a wedding to fund," he says.

"I pay all my taxes but I still mainly deal in cash. Now I am left with thousands of rupees worth of valueless notes. What am I going to do with them? Even if I change 4,000 rupees a day every day, it will take me months to convert all my money. I am educated and know what to do, but imagine the plight of a vegetable seller or milkman?"

'Incredible India'

Chiara Rossi is a tourist from Italy

Chiara Rossi, an Italian national who has been in India for six weeks, said the fiscal move had left her at a loss as to what to do with her foreign exchange.

"This is India and anything can happen but this is not fair. The government should have thought about tourists. I have 5,000 rupees and I am leaving India this evening. I don't know what to do with my money. It's frustrating."

- Published9 November 2016

- Published9 November 2016