Koh-i-Noor: Six myths about a priceless diamond

- Published

India has long claimed the diamond

The Koh-i-Noor is one of the world's most controversial diamonds.

It has been the subject of conquest and intrigue for centuries, passing through the hands of Mughal princes, Iranian warriors, Afghan rulers and Punjabi Maharajas.

The 105-carat gemstone came into British hands in the mid-19th Century, and forms part of the Crown Jewels on display at the Tower of London.

Ownership of the gem is an emotional issue for many Indians, who believe it was stolen from them by the British.

William Dalrymple and Anita Anand have written a book titled Kohinoor: The Story Of The World's Most Infamous Diamond, published by Juggernaut. Here the authors write about the main myths surrounding the priceless gem:

After the Koh-i-Noor came into the hands of the Governor-General Lord Dalhousie in 1849, he prepared to have it sent, along with an official history of the stone, to Queen Victoria.

Dalhousie commissioned Theo Metcalfe, a junior assistant magistrate in Delhi with a taste for gambling and parties, to undertake some research on the gem.

But Metcalfe accumulated little more than colourful bazaar gossip that has since been repeated in article after article, book after book, and even sits unchallenged on Wikipedia today as the true history of the Koh-i-Noor.

Below are six of the main "myths" taken on in the book:

Myth 1: The Koh-i-Noor is the preeminent Indian diamond

The jewel is in the crown worn by the Queen Mother, which was displayed on her coffin during her funeral

Reality: The Koh-i-Noor, which weighed 190.3 metric carats when it arrived in Britain, had had at least two comparable sisters, the Darya-i-Noor, external, or Sea of Light, now in Tehran (today estimated at 175-195 metric carats), and the Great Mughal Diamond, external, believed by most modern gemologists to be the Orlov diamond (189.9 metric carats).

All three diamonds left India as part of Iranian ruler Nader Shah's loot after he invaded the country in 1739.

It was only in the early 19th Century, when the Koh-i-Noor reached the Punjab, that the diamond began to achieve its preeminent fame and celebrity.

Myth 2: The Koh-i-Noor was a flawless diamond

Queen Victoria wearing a brooch set with the Koh-i-Noor

Reality: The original uncut Koh-i-Noor was flawed at its very heart.

Yellow flecks ran through a plane at its centre, one of which was large and marred its ability to refract light.

That's why Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, was so keen that it be re-cut.

The Koh-i-Noor is also far from being the largest diamond in the world: it's only the 90th largest.

In fact, tourists who see it in the Tower of London are often surprised by how small it is, especially when compared to the two much larger Cullinan diamonds, external that are displayed near it.

Myth 3: The Koh-i-Noor came from the Kollur mine in India in the 13th Century

Reality: It is impossible to know when the Koh-i-Noor was found, or where. That's what makes it such a mysterious stone.

Some even believe that the Koh-i-Noor is, in fact, the legendary Syamantaka gem from the Bhagavad Purana , externaltales of Krishna, one of the most popular Gods in the Hindu pantheon.

Indeed, according to Theo Metcalfe's report, tradition had it that "this diamond was extracted during the lifetime of Krishna".

What we do know for sure is that it wasn't mined at all, but unearthed from a dry river bed, probably in south India. Indian diamonds were never mined but found in alluvial deposits of dry river beds.

Myth 4: The Koh-i-Noor was the Mughals' most precious treasure

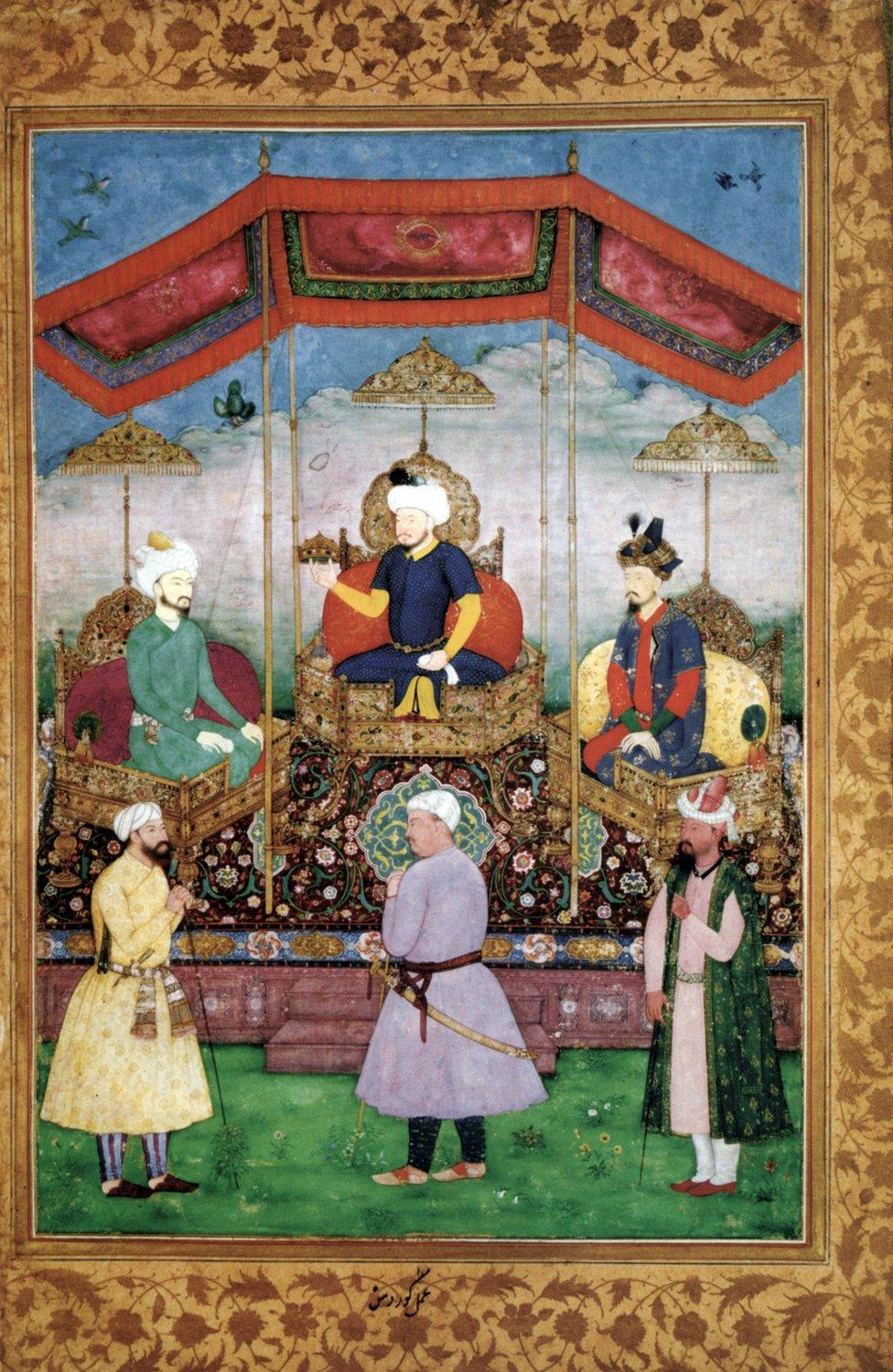

Timur handing the imperial crown to Babur in the presence of Humayun. Babur's famous diamond, which he gave to Humayun, may have been the Koh-i-Noor

Reality: While Hindus and Sikhs prized diamonds over other gems, Mughals and Persians preferred large, uncut, brightly-coloured stones.

Indeed in the Mughal treasury, the Koh-i-Noor seems to have only been one among a number of extraordinary highlights in the greatest gem collection ever assembled, the most treasured items of which were not diamonds, but the Mughals' beloved red spinels from Badakhshan and, later, rubies from Burma.

In fact, Mughal emperor Humayun even gave away Babur's diamond - widely thought to be the Koh-i-Noor - to Shah Tahmasp of Persia as a present when he was in exile.

Babur's diamond eventually wound its way back to the Deccan but it's unclear how or when it found its way back into the Mughal court thereafter.

Myth 5: The Koh-i-Noor was sneakily stolen from Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah Rangila on the pretext of a ceremonial turban swap

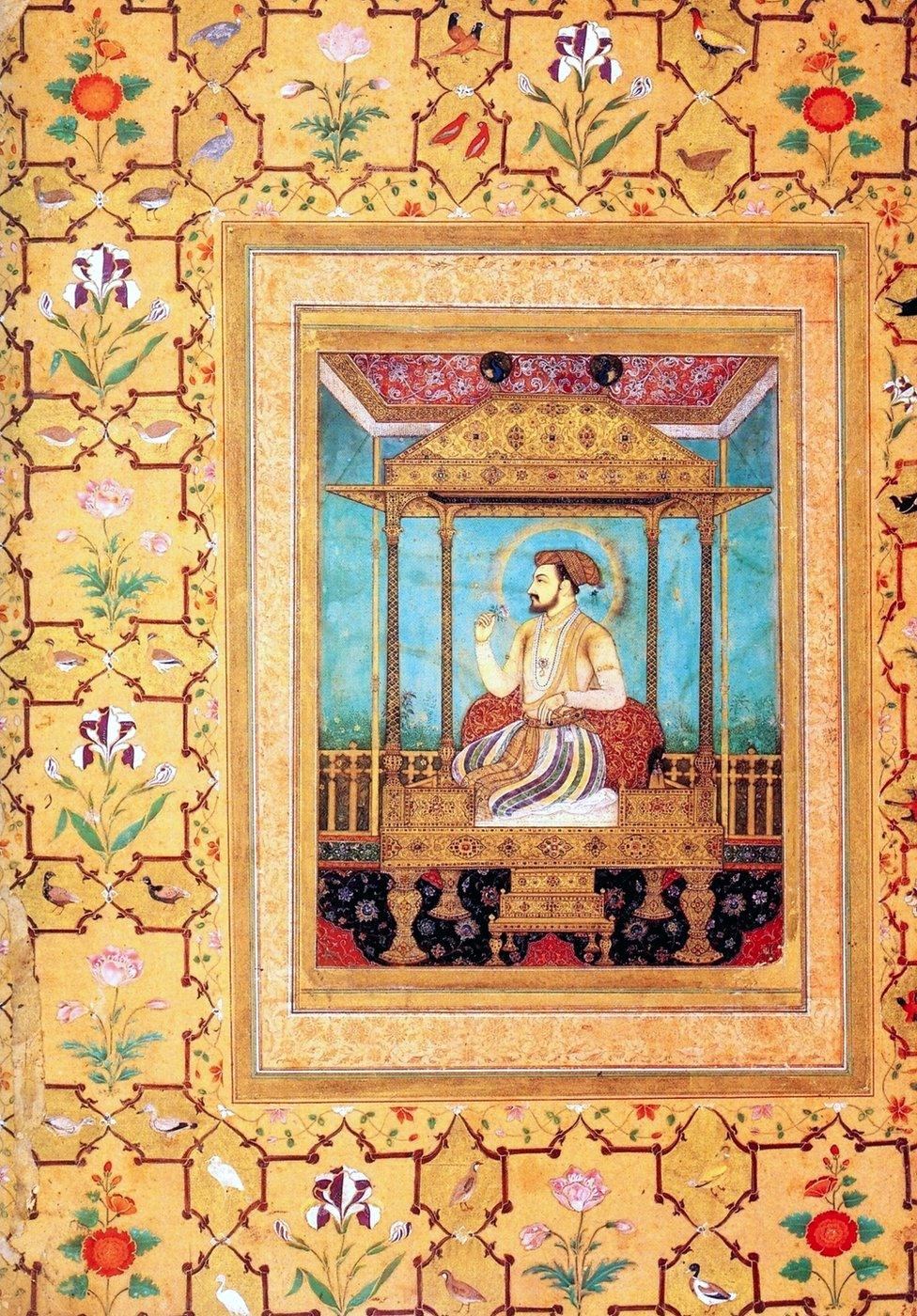

Shah Jahan seated on his richly jewelled Peacock Throne

The popular story is that Nader Shah connived to deprive the Mughal emperor of his diamond, which had been squirreled away in his turban.

But, it was far from being a loose, singular gem that Muhammad Shah could secrete within his turban, and which Nader Shah could craftily acquire by a turban swap.

According to the Persian historian Marvi's eyewitness account, the Emperor could not have hidden the gem in his turban, because it was at that point a centrepiece of the most magnificent and expensive piece of furniture ever made: Shah Jahan's Peacock Throne.

The Koh-i-Noor, he writes from personal observation, in the first named reference to the stone - until now untranslated into English - was placed on the roof of this extraordinary throne, set in the head of a peacock.

Myth 6: The Koh-i-Noor was cut rather clumsily by a Venetian cutter and polisher of stone, which reduced its size significantly.

Reality: According to French gem merchant and traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who was given permission from Mughal emperor Aurangzeb to see his private collection of jewels, the stone cutter, Hortensio Borgio, had indeed brutally cut a large diamond, resulting in a sad loss of size.

But he identified that diamond as the Great Mughal Diamond that had been gifted to Mughal king Shah Jahan by diamond merchant Mir Jumla.

Most modern scholars are now convinced that the Great Mughal Diamond is actually the Orlov,, external today part of Catherine the Great's imperial Russian sceptre in the Kremlin.

Since the other great Mughal diamonds have largely been forgotten, all mentions of extraordinary Indian diamonds in historical sources have retrospectively come to be assumed to be references to the Koh-i-Noor.