Why a problem of plenty is hurting India's farmers

- Published

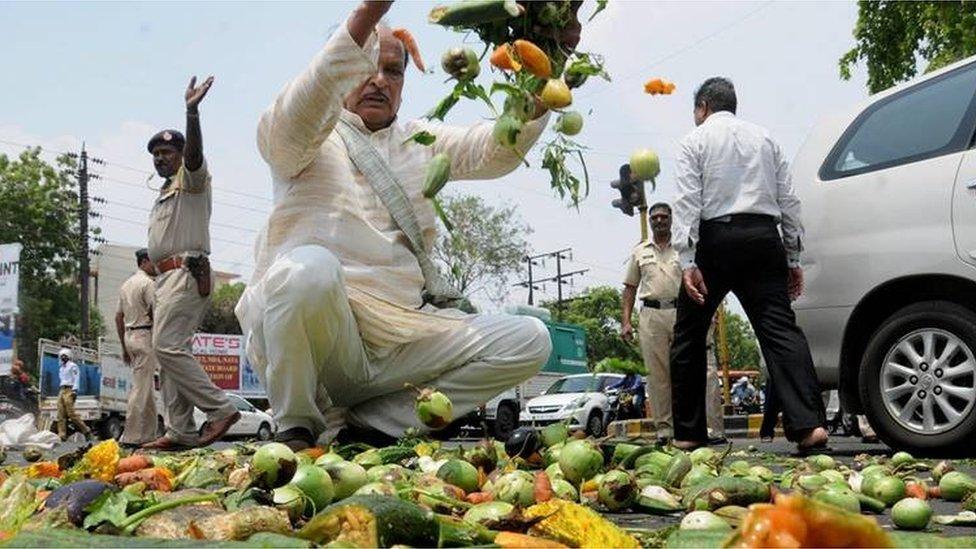

Farmers in Maharashtra have dumped their produce on the roads in protest against low prices

Farmers are on the boil again in India.

In western Maharashtra, external state, they have been on strike for a week in some seven districts now, spilling milk on the streets, shutting down markets, protesting on the roads and attacking vegetable trucks. In neighbouring Madhya Pradesh, curfew has been imposed after five farmers were killed in clashes with police on Tuesday. Last month, farmers in southern Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, external staged protests and burnt their red chilli crop.

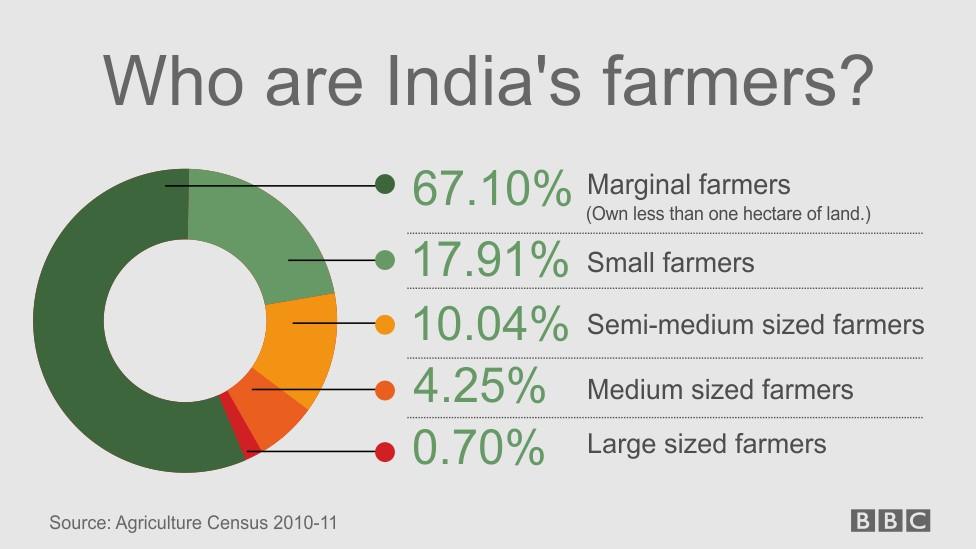

The farmers are demanding waivers on farm loans and higher prices for their crops. For decades now, farming in India has been blighted by drought, small plot sizes, a depleting water table, declining productivity and lack of modernisation.

Half of its people work in farms, but farming contributes only 15% to India's GDP. Put simply, farms employ a lot of people but produce too little. Crop failures trigger farm suicides with alarming frequency.

The present unrest is, however, rooted in a problem of plenty.

In Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, the farmers are on the streets because a bumper harvest fuelled by a robust monsoon has led to a crop glut. Prices of onions, grapes, soya-bean, fenugreek and red chilli, for example, have nosedived.

In most places, the governments have been less than swift in paying the farmer more for the crops - the government sets prices for farming in India and procures crops from farmers to incentivise production and ensure income support.

So why has a bumper crop led to a crisis in farming?

Some believe that the price crash is the result of India's controversial withdrawal of high value banknotes - popularly called demonetisation - late last year.

The ban, surprisingly, did not hurt planting as farmers "begged and borrowed" from their kin and social networks to pay for fertilisers, pesticides and labour, Harish Damodaran, rural affairs and agriculture editor at The Indian Express newspaper told me.

So more land was actually cropped, and bountiful rains led to a bumper crop. But traders, Mr Damodaran believes, possibly did not have enough cash to pick up the surplus crop.

"Although the chronic cash shortage has passed, there is still a liquidity problem. I have been talking to traders who say there's not enough cash, which remains the main medium of credit in villages. I suspect the price crash has been caused by a lack of cash."

'Exaggerated fears'

A prominent trader in Lasangaon, Asia's biggest onion market in Maharashtra, a state which accounts for a third of India's annual production, told me that concerns over shortage of cash leading to crop price crashes were "exaggerated".

"There has been a good crop for sure, but a lot of traders have picked up crop, paying cash, issuing cheques and using net banking. Some of the glut and wastage has been due to the ongoing strike, when trucks of vegetables have been attacked on the highways," Manoj Kumar Jain said.

Still others believe the main reason for the ongoing crises actually rooted in India's chronic failure of coping with surplus harvests because of lack of adequate food storage and processing capacity.

"If the rains are good, you end up with a glut of crops and prices crash. The glut only highlights the inefficiencies of the farming value chain and hits farmers," Ashok Gulati, an agriculture specialist at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, told me.

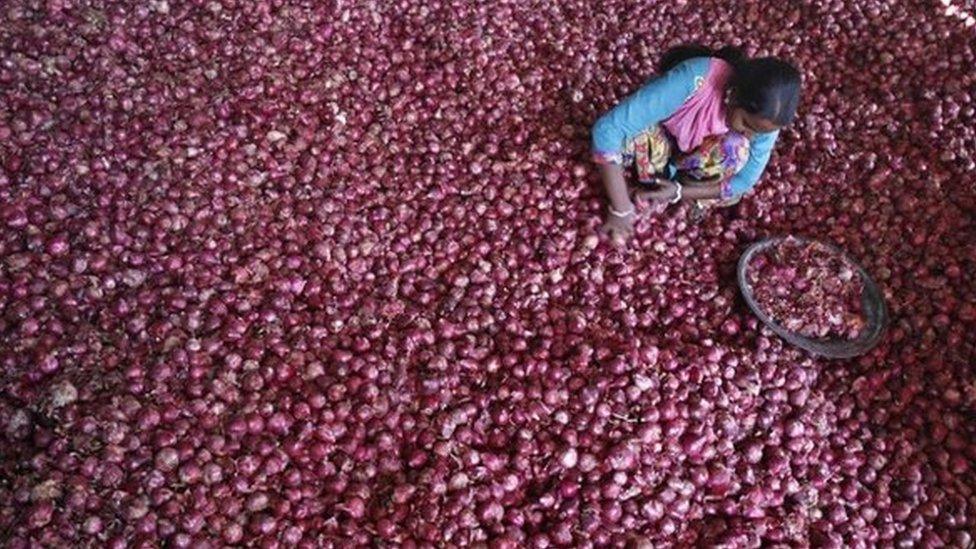

Take onions, for example. The vegetable is 85% water and loses weight quickly.

India is one of the world's biggest onion producers

In Lasangaon, traders buy the crop from farmers and store the onions on concrete in tarpaulin-covered sheds. If the weather stays right, 3-5% of the stored crop is wasted in storage. But if the mercury soars, more onions dry up, lose weight and 25-30% of the stored crop could be wasted.

In a modern cold storage, however, onions can be stored in wooden boxes at 4C. Crop wastage is less than 5%. Storage costs about a rupee (less than a US cent) for every kilogram of onion a month.

So the government needs to make sure - or even subsidise - to keep the vegetable affordable to consumers once it reaches the retail market.

"We need to make the supply storage chain so efficient that the customer, farmer and the storage owner are happy. Unfortunately India hasn't been able to make that happen," Dr Gulati said.

Poor storage

For one, India just doesn't have enough cold storages.

There are some 7,000 of them, mostly stocking potatoes in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. Resultantly, fruits and vegetables perish very quickly. Unless India hoards food effectively, a bumper crop can easily spell doom for farmers.

Secondly, there's not enough processing of food happening to ensure that crops don't perish or go waste.

Take onions, again.

One way to dampen volatility in onion prices is to dehydrate the bulb and make these processed onions more widely available. Currently, less than 5% of India's fruit and vegetables is processed.

Thirdly, farmers in India plant for new harvest looking back at crop prices in the previous year.

If the crop prices were healthy, they sow more of the same, hoping for still better prices.

If the rains are good, a crop glut can happen easily, and lead to extraordinary fall in prices. Farmers hold on to the crops for a while, and then begin distress sales.

Half of its people work in farms, but farming contributes only 15% to India's GDP

"You need to allow future prices through contract farming, not cropping based on last year's prices," says Dr Gulati.

Radical measures

Clearly, farming policies in India need a radical overhaul.

Punjab, India's "granary", is a perfect example.

At a time when India does not suffer food shortages, water-guzzling wheat and rice comprise 80% of its cropped area and deplete groundwater.

Rising production of cereals has meant that government has been giving paltry rises to the farmers while buying paddy and wheat, eroding their profitability.

"They [the policies] are distorting the choices that farmers make - those who should be finding ways to grow vegetables, which grow more expensive every year, are instead growing wheat we no longer need," says Mihir Sharma, author of Restart: The Last Chance for the Indian Economy.

But the best that the governments here do is to quickly raise crop buying prices and alleviate the farmers' suffering.

Faced with a crop glut at home, the newly appointed BJP government in Uttar Pradesh was smart enough to promptly raise the procurement price of potatoes - and announce a controversial farm loan waiver - and quell a simmering farmers' revolt .

The government in Madhya Pradesh, ruled by the same party, failed to act in time. Now it says it will pay more to buy off the surplus onions. The more things change, the more they remain the same.