Why aren't Indians angrier over note ban failure?

- Published

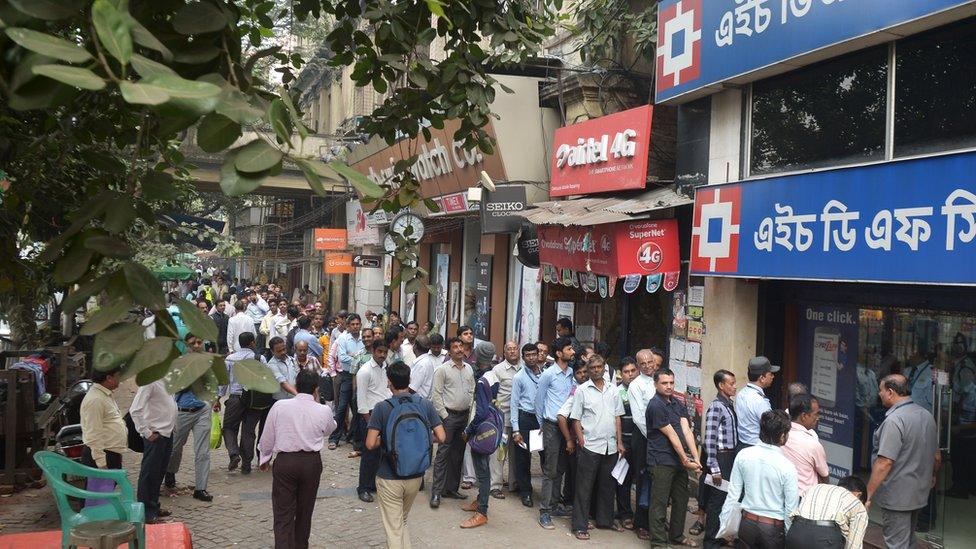

At one point it seemed the entire 1.2 billion population of the world's seventh biggest economy had joined a giant bank queue

You might imagine that people here in India would be angry at the news that Prime Minister Narendra Modi's audacious attempt to crack down on the scourge of "black money" had failed.

The surprise cancellation of 86% of the country's currency caused huge disruption.

At one point it seemed the entire 1.2 billion population of the world's seventh biggest economy had joined a giant bank queue.

But this was much more than an issue of inconvenience, everyone was affected.

Remember, virtually all transactions in India are conducted in cash.

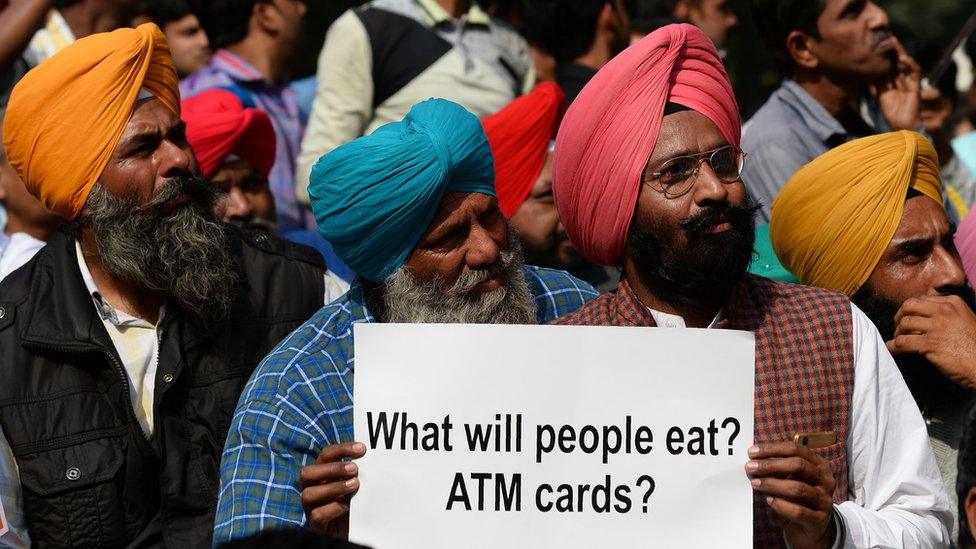

Businesses stalled, lives were disrupted. Lots of people barely had the money to buy food.

"We never expected that we would be reduced to becoming destitute in this manner," one of the hundreds of thousands migrant workers who lost their jobs told the BBC in the days after the policy was announced.

"We never expected our children to go hungry."

After 500 and 1,000 rupee notes were scrapped, Indian residents had to adjust to life, starting with waiting in queues for hours to deposit their cash

The cash crisis touched every aspect of life.

"It's my daughter's wedding tomorrow and I need money to pay for everything. I have nothing at the moment," worried an anxious father in the eastern state of Bihar.

"They told us to deposit our old money so I have given the bank everything I had, now they are not giving me anything back."

With tens of millions of people suffering distressing consequences you'd have thought there would be some blowback for the government now that we know almost all the cash was returned.

So why hasn't the country risen up in fury?

One reason is that lots of people find all the big numbers and complex details difficult and - frankly - dull.

You only need to look at the hundreds of news websites in India to see that. The story barely makes the list of top stories on the sites of the leading TV stations or even the country's biggest newspaper.

Another explanation is the success Mr Modi has had in spinning his note ban as a bold attempt to strike a blow to the rich and powerful on behalf of the poor.

"Those who have indulged in corruption by cheating the poor, cannot have a good night's sleep," he thundered from the ramparts of the Red Fort two weeks ago on the anniversary of India's independence.

The decision was taken to crack down on corruption and illegal cash holdings known as "black money"

Thanks to demonetisation, he continued, "no one is allowed to cheat in the country any more, everyone is answerable."

The figures from the Reserve Bank of India may suggest the policy did not achieve that but, in a country riven with inequality, Mr Modi's message hit home hard.

In part that is also because the government changed the emphasis of the policy as soon as it became clear that it wasn't working out quite as planned.

First off, demonetisation was all about tackling so-called "black money".

"There comes a time in the history of a country's development when a need is felt for a strong and decisive step," is what Mr Modi said when he launched the policy on the 8 November last year.

"For years, this country has felt that corruption, black money and terrorism are festering sores, holding us back in the race towards development."

But within a few weeks of that announcement it was already clear that far more money was coming back than the government had expected.

So the talk became more about how the policy was a tool to persuade Indians to use less cash and enter the so-called "digital economy".

"We can now see a positive momentum towards digital transactions in India," said Mr Modi in a New Year address. "More and more people are transacting digitally."

More than half of Indians still don't have a bank account, and some 300 million have no government identification

There certainly was a dramatic increase in digital transactions but, at the same time, the International Monetary Fund cut its growth forecast for India by one percentage point.

The other objective that came to the fore was the effort to tackle India's rampant tax evasion.

Because so much business is done in cash here it is very easy to evade tax - and many, many Indians do. Figures released last year showed just 1% of the population paid income tax in 2013.

This is one area where the policy may have actually been quite successful.

Between 1 April and 5 August more than 5.6 million people filled in their income tax returns this year, according to Mr Modi. Last year the figure was just 2.2 million over the same period.

But boredom and political spin aside there is another, even more compelling reason why Indians aren't more annoyed about the shortcomings of the policy.

The truth is that, nine months on and the worst hardships of demonetisation are over and, in a country as poor as India, most people have more pressing issues to think about than whether or not a government policy, however disruptive, has worked.