Can India's currency ban really curb the black economy?

- Published

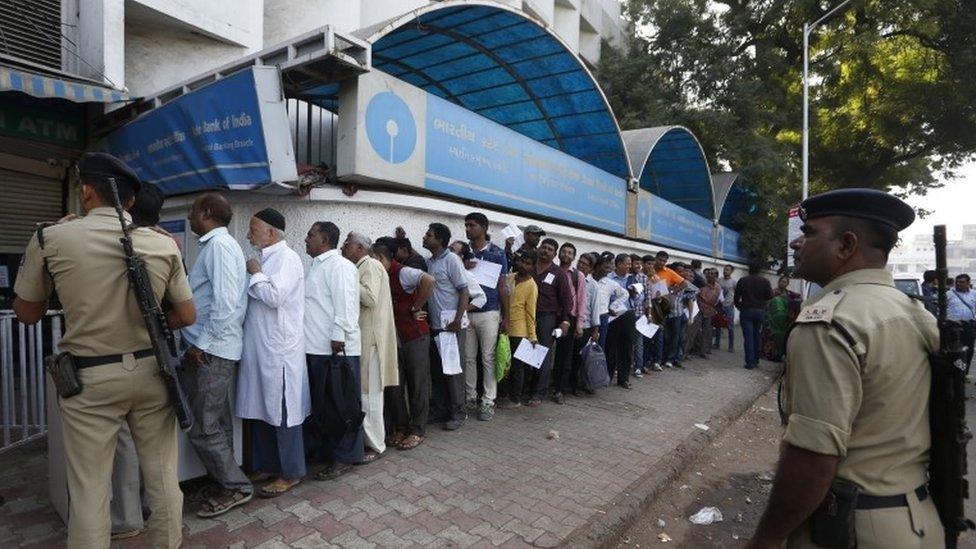

People are lining up outside banks on Thursday to get the new currency notes

On Tuesday night, in an unusual broadcast to the nation, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi scrapped 1,000 and 500 rupee notes in a bid to flush out tax evaders. The banknotes that were declared illegal tender represent more than 86% of cash in circulation in India. Economic analyst Vivek Kaul explains the fight against tax evasion.

The notes which have been withdrawn can be deposited in banks as well as post offices until 30 December and the money will be credited into the account of the individual depositing the money. Up to 4,000 rupees can also be exchanged in the bank.

While Indian cities are full of bank branches, those living in rural areas will find exchanging the old notes a little difficult. Only 27% of Indian villages have a bank within 5km (three miles).

The idea behind this move, the government says, is to curb "financing of terrorism through the proceeds of fake Indian currency notes and use of such funds for subversive activities such as espionage, smuggling of arms, drugs and other contraband into India".

Armed policemen have been deployed outside many banks to control and manage the crowds

It is also to hit those who have a massive amount of "black money" in the form of cash.

Black money is essentially money that has been earned - either through legal activities or through corruption - without any tax being paid on it.

There are several estimates of the total amount of black money going around in the Indian economy. A World Bank estimate puts the size of the black economy at 23.2% of India's total economy in 2007.

Shock as India scraps 1,000 rupee notes

Ideas from India to use and abuse redundant cash

'No customers': Indians react to currency ban

By making high denomination bank notes worthless overnight, the government hoped that those who had black money in this form would not be able to convert it into physical assets like gold.

News reports suggest that jewellers in many parts of the country worked overtime through the night of 8 and 9 November to help convert 500 and 1,000 rupee notes into gold.

Starting Thursday, new 2,000 rupee (about $30; £24) and 500 rupee notes will be injected into the economy over the next "three to four weeks".

The old 500-rupee notes are now worth nothing

Those who have black money will try exchanging it for new notes.

But they cannot simply go to a bank and deposit all their old cash, given that it is likely to lead to questions from the income tax department.

Any other way of exchanging notes will take some doing, given that the old denomination notes form more than 86% of notes in circulation by value.

Hence, it will not be easy to exchange these notes without leaving audit trails for the income tax department.

The major idea behind the move seems to be to incapacitate those who are holding a lot of black money in the form of cash.

Crisil Research expects income tax collections of the government to improve as money earlier unaccounted for enters the banking system and eventually gets taxed.

Reports says jewellers in many parts of the country worked overtime through the night of 8 and 9 November to help convert 500 and 1,000 rupee notes into gold

Inflation is also expected to come down in the short-term as cash transactions come down.

Another area which is likely to be impacted is real estate, since a portion of the payment while buying a house in India is almost always made in the form of cash.

With the high denomination notes having been taken out of circulation, it will become very difficult to organise for this payment and so prices are expected to fall.

If prices do fall, it will make real estate affordable. At affordable prices, the demand for real estate is likely to go up.

This is expected to create low-skilled and unskilled jobs which the country badly needs, given that one million individuals enter the workforce every month.

But the retail as well as the luxury goods businesses where the bulk of transactions are carried out in cash are expected to be hit as cash transactions will come down dramatically in the short term.

In fact, while the old notes are being withdrawn and the new notes make it to the market, cash transactions are likely to remain down.

India is a country where most transactions are still carried out in cash.

A 2012 estimate, carried out by The Fletcher School at the Tufts University, estimated that 86.6% of the transactions were in cash.

An area likely to be impacted is real estate since a portion of the payment while buying a house in India is almost always made in the form of cash

While this figure would have come down since then, it will still be at a very high level.

Another research paper, entitled The Cost of Cash in India, points out that "the ratio of currency to GDP in India (12.2%) is higher than countries such as Russia (11.9%), Brazil (4.1%), and Mexico (5.7%)". Hence, India is still largely a cash-driven economy and given this, the government's move is likely to cause a few problems in the short term.

Also, if the government is serious about tackling the black money menace, it shouldn't just leave it at this.

As the former central bank governor Raghuram Rajan said: "I think there are ways around demonetisation. It is not that easy to flush out the black money. Of course, a fair amount may be in the form of gold, therefore even harder to catch."

It is important that the government uses information technology to track down those who are earning money but not paying their share of taxes.

As Mr Rajan put it: "I would focus more on tracking data and better tax administration to get at where money is not being declared."

Further, the government needs to quickly introduce electoral financing reform in the country. Most elections in India are fought using black money.

Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy

- Published9 November 2016

- Published10 November 2016