Did the British Empire resist women’s suffrage in India?

- Published

The US took 144 years to give equal voting rights to women. Suffragettes in UK took nearly a century to win the vote. Women won the vote in some cantons of Switzerland as recently as 1974. But Indian women got the right to vote the year their country was born.

Ornit Shani, author of an excellently researched new book on how India received universal adult franchise in 1947, says the move was a "staggering achievement for a post-colonial nation" in the midst of a bloody partition that killed up to a million people and displaced 18 million others.

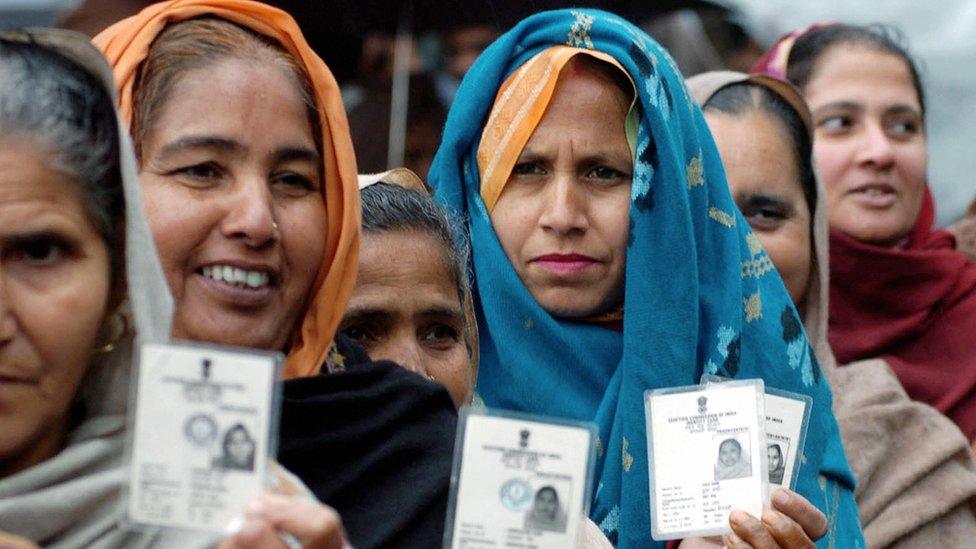

In independent India, the number of voters leapt more than five-fold to 173 million people - nearly half of the total population - and included 80 million women. Some 85% of them had never voted before. (Unfortunately, 2.8 million women voters had to be excluded from the rolls because they failed to disclose their names.)

But, as Dr Shani's book, How India Became Democratic: Citizenship at the Making of the Universal Franchise, shows women's suffrage, unlike under colonial rule was not questioned.

British officials had unfailingly argued that the universal franchise was a "bad fit for India," says Dr Shani. Elections in colonial India were exercises in restricted democracy with a limited number of voters casting their ballots in seats allotted along religious, community and professional lines.

In the beginning, Mahatma Gandhi did not support women gaining the vote, and urged them to help men fight the colonial rulers. But, as historian Geraldine Forbes writes, Indian women's organisations fought hard to demand voting rights for women.

In 1921, Bombay (now Mumbai) and Madras (now Chennai) became the first provinces to give the limited vote to women. Between 1923 and 1930, seven other provinces allowed women franchise.

British officials had argued that the universal franchise was a "bad fit for India".

The House of Commons ignored demands for voting rights by a number of Indian - and British - women's organisations, writes Dr Forbes, in her engaging book, Women in Modern India.

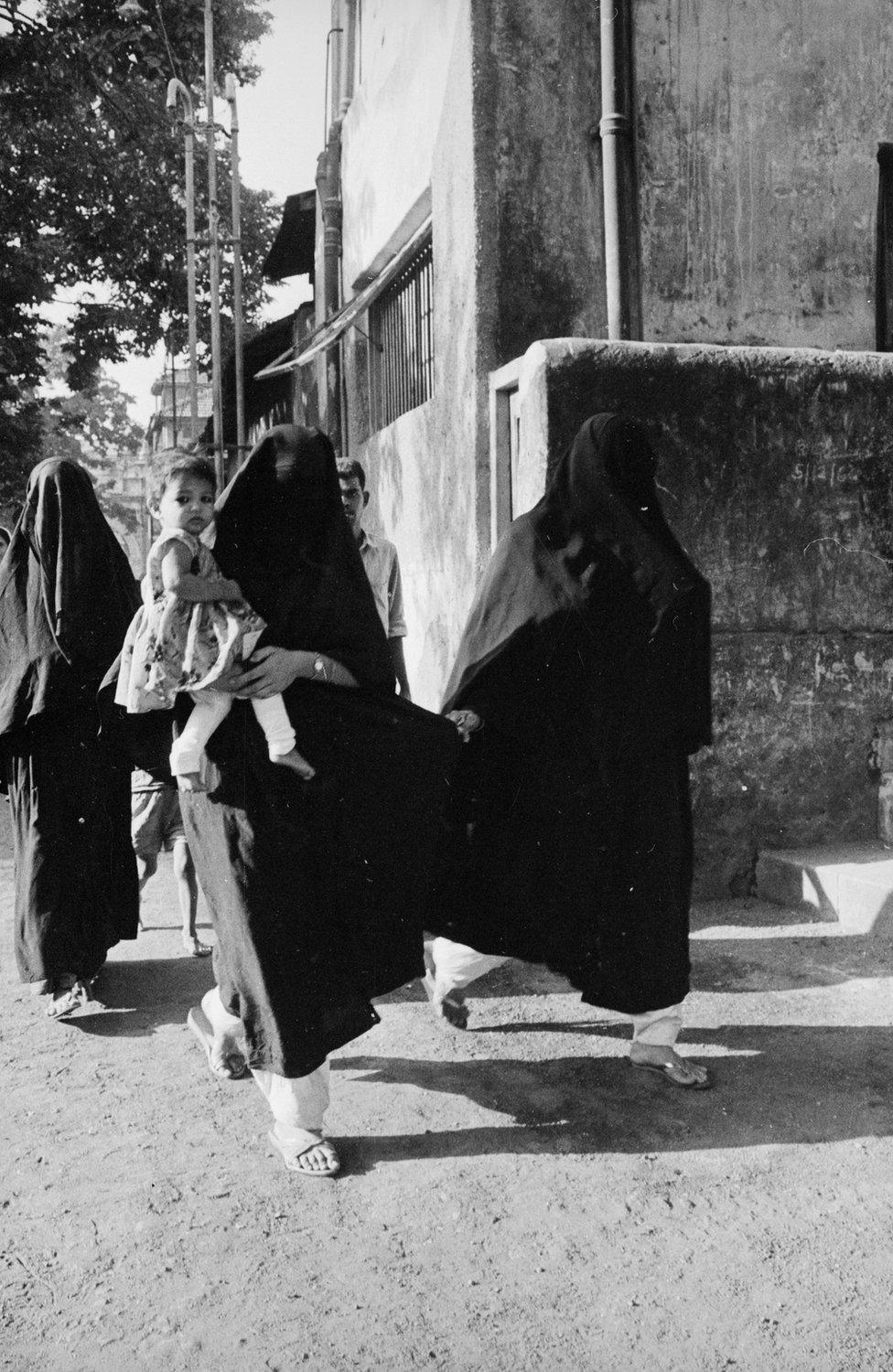

Women who lived in the purdah (female seclusion) appeared to be a convenient excuse for this denial.

"Obviously, the British promise to safeguard the rights of minorities meant only male minorities. In the case of women, the majority were denied rights because the minority lived in seclusion," writes Dr Forbes.

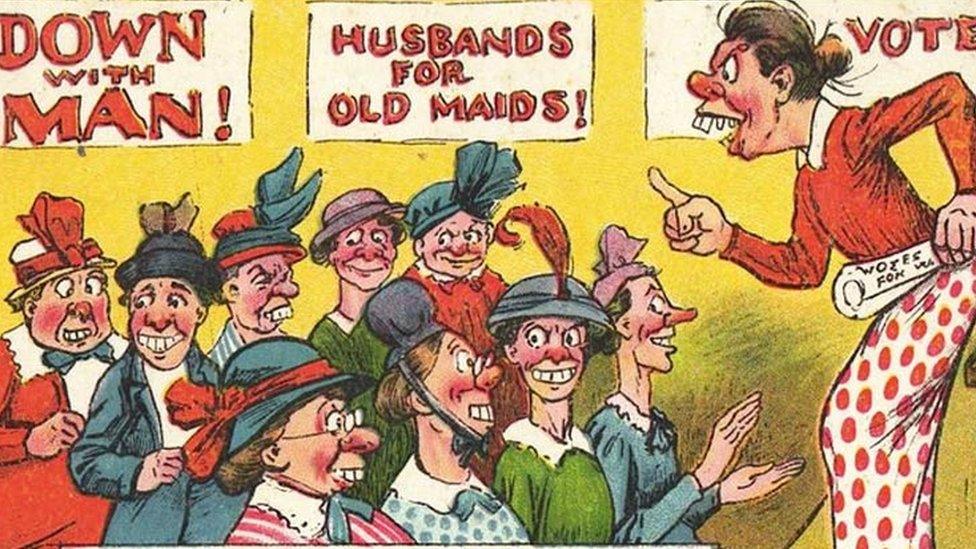

Colonial administrators and legislators - both Indian and British - resisted moves to expand the franchise. Opponents of the vote, according to Dr Forbes, "talked of women's inferiority and incompetence in public affairs".

Some said giving women the vote would result in the neglect of husbands and children; "one gentleman even argued that political activity rendered women incapable of breast feeding," she writes.

In independent India, the number of voters included 80 million women.

A suffragette, Mrinalini Sen, wrote in 1920 that although women were subject to "all the laws and rules of the land exercised by the British government" and had to pay taxes if they owned property, they could not vote. "It was as if the British were telling women not to go to the courts for justice but rather seek it at home," she said.

Under the The Government of India Act, 1935 - the last colonial legal framework for India - suffrage was extended to a little more than 30 million people or about a fifth of the adult population. A small number of them were women.

The government of the province of Bihar and Orissa (the two states made up a single province at the time) attempted to reduce the number of voters and take away voting rights from women. The government, writes Dr Shani, also believed that a "woman's name should be removed from the electoral roll if she is divorced, or if her husband dies or loses his property".

But when officials came across a matriarchal community - as they did in the Khasi hills in India's northeast - where women held property in their names, they saw this as a "pretext for an exception".

Provinces also made their own rules over enrolling women. In Madras, a woman could qualify to be a voter only if she was a pensioned widow or the mother of an officer or soldier or her husband was a tax-payer, implying that he owned property.

In 1948, many women refused to give their names.

So a woman's eligibility to vote largely depended on her husband - and his qualifications and his social position.

"The notion of conferring the right to vote and bringing women genuinely into the electoral roll was beyond the purview of the bureaucratic colonial imagination," says Dr Shani.

"It was also consistent with the colonial government's lack of faith in India's illiterate masses and their negative attitudes towards enfranchisement of people at the margins of the franchise, such as the poor and rural, illiterate people."

Things changed when independent India decided to give the universal franchise to its people.

Work on preparing the draft electoral roll began in November 1947. By the time India had her own constitution in January 1950, the "notions of universal franchise and electoral democracy were already grounded," says Dr Shani.

But there were problems when the preparation of the draft electoral roll began in 1948.

India ranks 148 out of 190 countries for the number of women in its parliament.

Officials in some provinces said the recording of women's names presented difficulties. Many women refused to give their names, introducing themselves as the wife, daughter or widow of a man. The government made it clear that this was not permissible, and that women had to register as individuals.

Contrary to the earlier colonial practices, the government had made it clear that women had to be registered as individual voters and not as relations of others. The government began media publicity to encourage women to register by their names. Women's organisations also appealed to women to register as voters so that they could send their representatives to safeguard their interests.

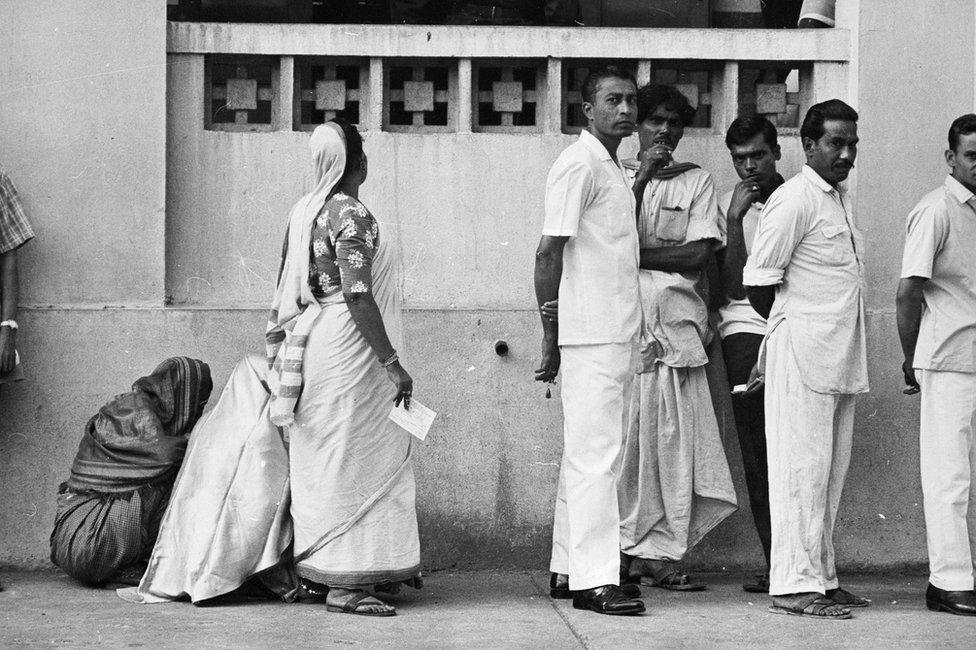

A candidate who contested a parliamentary seat in the first elections - held between October 1951 and February 1952 - in a rural constituency in Madras reported that "rural voters, men and women, waited patiently for hours and cast their ballots. Veiled Muslim women, he reported, had exclusive booths to themselves."

This was a major triumph.

Of course, the fight continues. A bill to reserve 33% of the seats in the lower house of India's parliament for women has been stuck since 1996 in the face of stiff opposition.

Even though more women are voting than before and sometimes even outnumbering men, this is not translating into parliamentary seats for women. A 2017 UN report ranked India 148 among 190 countries, external for the number of women in its parliament - they accounted for just 64 seats in the 542-member lower house.

Ornit Shani's book How India Became Democratic: Citizenship and the Making of the Universal Franchise, is published by Cambridge University Press. The South Asia edition is with Penguin Random House.

- Published9 April 2014

- Published16 April 2014

- Published6 February 2018