A day in the life of India's 'tuberculosis warrior'

- Published

On world tuberculosis (TB) day, public health specialist Chapal Mehra describes the work of Dr Zarir Udwadia, who has been working tirelessly to fight the disease in its often untreatable forms.

When Dr Udwadia, an acclaimed pulmonologist, wrote in a medical journal in 2012 about a virtually untreatable form of TB, the ordinary Indian did not know who he was.

But the letter set off a frenzy in the medical community and eventually made him one of India's best known doctors, and a man who reminded the country of its growing epidemic of TB and drug-resistant TB (DR TB) - a type of tuberculosis which is unresponsive to at least two of the first line of anti-TB drugs.

India is is the global TB epicentre - the country records 2.8 million new tuberculosis cases annually, of which more than 100,000 are multi-drug resistant (MDR), according to the World Health Organization.

The disease kills 400,000 Indians every year, and costs the government around $24bn (£19.2bn) annually.

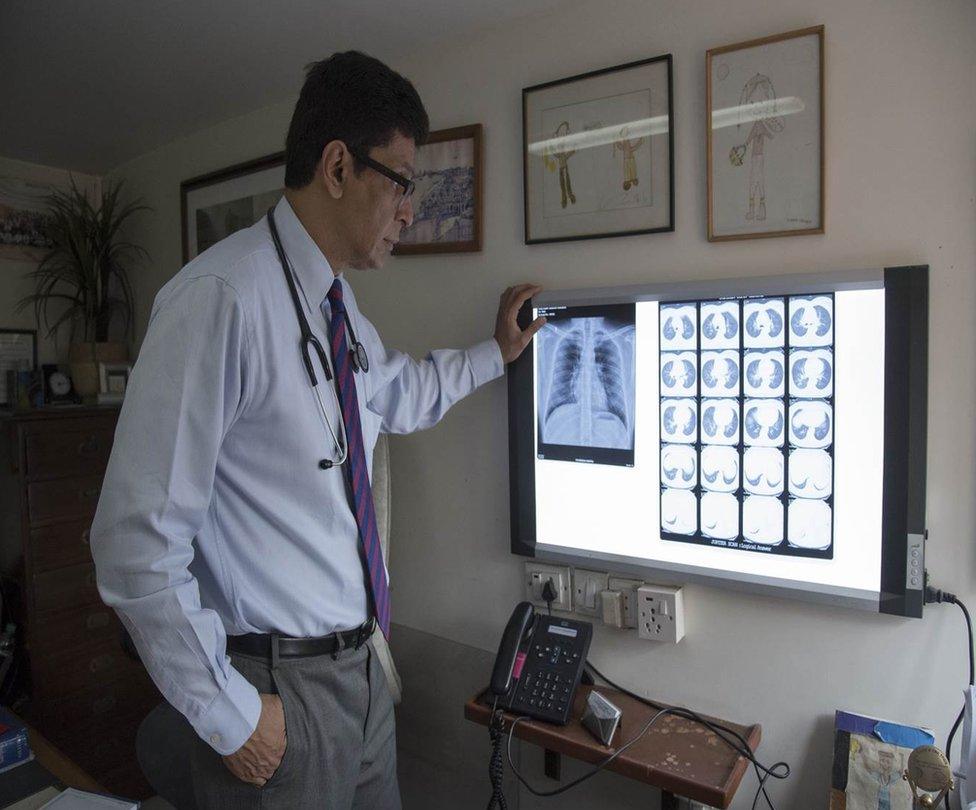

Why is TB diagnosis a challenge? "Because India continues to rely heavily on outdated diagnostic techniques, some of which miss about 50% of all TB cases," says Dr Udwadia, who is based in the western city of Mumbai, India's financial capital.

He believes India needs to adopt newer technologies such as the GeneXpert, a molecular test that detects the presence of TB bacteria.

"We need to scale up the GeneXpert and make it the first test for everyone like they do in South Africa."

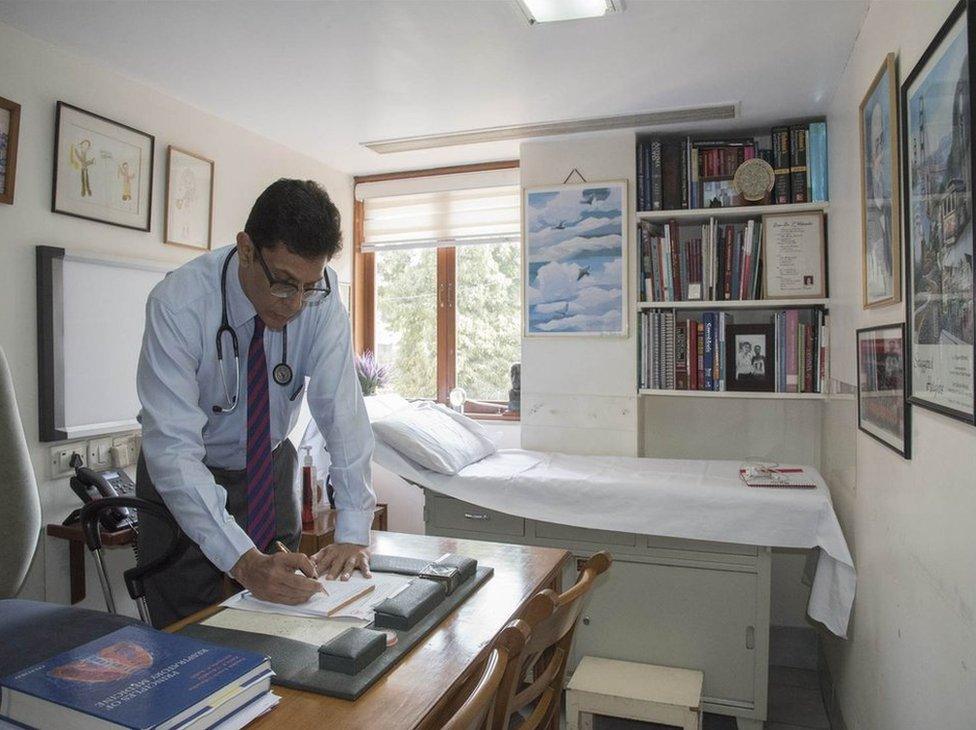

Dr Udwadia is often termed the miracle worker or the saviour by his patients. The most critical patients, often those with virtually no hope, and their families, crowd his free clinic, waiting with files of records and X-rays. Many wait overnight hoping to be seen by him.

Even though the government once found his findings questionable, it has more recently discovered in him an enabling critic who is helping India's fight against the deadly infection.

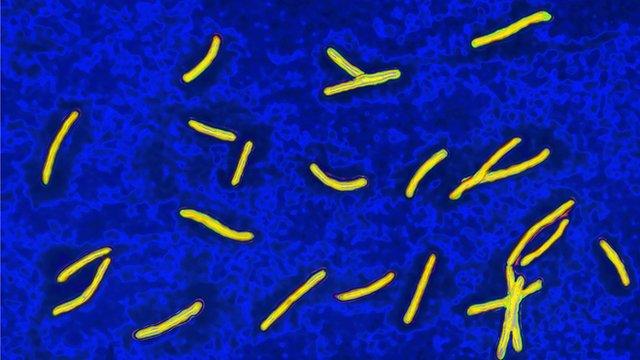

"TB is much more than just a medical affliction caused by a specific bacterium," says Dr Udwadia. "It is a strange, terrible and fascinating entity. Every death from TB is an avoidable tragedy. It is our task to reverse the tide."

Though treatable, TB kills an Indian every minute and is an engine of poverty, debt and suffering. It remains India's severest health crisis- one which needs urgent action.

"Normal TB is really easy to treat, four drugs over six months at a cost of $5 will almost always cure you," says Dr Udwadia.

But, he adds, if patients are given the wrong drugs or incorrect doses, or are irregular with their medication, the TB bacteria becomes resistant to the drugs.

This drug-resistant TB takes far longer - up to two years - and thousands of dollars to treat. It requires many more drugs - 250 injections and 15,000 pills, to be precise.

"When stacked up [the pills] equal a 30-storey tower," says Dr Udwadia. And the drugs that are toxic can have severe side effects, he adds. "They can make you deaf, blind, give you kidney failure and leave you psychotic."

TB can cause damage to the lungs

Drug-resistant TB

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is caused by a bacteria that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs.

Extensively drug resistant TB (XDR TB) is a rare type of MDR TB that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs, such as amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin).

"Every now and then, I come across patients who are virtually untreatable," he says.

Dr Udwadia describes MDR-TB, which is resistant to multiple drugs, as a "ticking time bomb" that could reverse the progress India has made so far in its battle against the infection.

"In our crowded communities, each MDR patient infects 10-20 others with the same deadly strain ensuring the epidemic amplifies relentlessly."

He recalls one of his patients, Salma, a poor woman who lived in Dharavi, a sprawling slum that lies at the heart of Mumbai. Nearly a million people are estimated to live in an unending stretch of narrow lanes, open sewers and cramped homes.

It is "an incubator of TB by virtue of its poverty and overcrowding", according to Dr Udwadia.

Salma, he says, had spent five years trying to cure herself of her TB infection. She had travelled for more than 1500km (932 miles), visited at least four government TB clinics, seen 12 private physicians and received multiple drugs in various combinations.

"What could be more soul destroying than taking five years of treatment but finding yourself getting worse, not better?" asks Dr Udwadia.

Salma, who was resistant to every single TB drug, died four days after a surgery.

"So who killed Salma? Who let her down? We did! drug-resistant TB is a collective indictment of us all."

In the last year alone, Dr Udwadia says, 10 million people across the globe have got sick with TB, two million have died of it and about 150,000 patients of drug-resistant TB in India are desperate for a cure.

"All they get is delays, disruptions and disillusion," he says.

Referring to India's launch of its first bullet train project in September 2017, he adds, "forget your bullet trains, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and just help our patients get on this one.

"Give us the new drugs we need to treat, give us the labs and tests to diagnose early, give us more funds, not more cuts in the TB budget, and give us social change, because TB is the perfect expression of an imperfect civilisation."

Photographs by Shampa Kabi.

- Published24 March 2017

- Published27 March 2014

- Published22 November 2017