India's Gorakhpur hospital: The night the children died

- Published

Israuti Devi (left) lost a newborn grandchild that night

On the night of 10 August 2017, some 30 children died at a hospital in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, highlighting chronic malaise in the public health system. The hospital and state government denied the deaths were caused by a lack of liquid oxygen after bills went unpaid.

"She was alive until the morning and then after half past six I saw her shake and crumble in front of my eyes."

Mohamed Zahid's five-year-old daughter Khushi was among those who died at Baba Raghav Das Hospital in Gorakhpur.

It was the first time the family had gone to a government hospital and Mr Zahid feels guilt ridden. There was no offer of a post mortem - which would be routine in many other countries - into any of the deaths that night.

But he is convinced he knows why his daughter and other infants died: "I'll tell you why, because they didn't have oxygen! If my daughter had had sufficient oxygen she'd have survived."

Mr Zahid was sent home with Khushi's shrouded body within hours of her dying - her death certificate, a scrap of paper with something scribbled on it, resembled a receipt from a shop. The family say they have not received any of the 50,000 rupees (about $770; £550) in compensation promised by state authorities.

Twenty-four hours earlier, Khushi had been playing with her dolls on the stairs of their home in a run-down suburb of Gorakhpur. Like many of the children who died that night, she was a victim of encephalitis.

Mohamed and Rehana Zahid lost their five-year-old daughter Khushi

Encephalitis is an infection that leads to inflammation of the brain and is especially dangerous to young children. The condition is rife in eastern Uttar Pradesh and looking around Mr Zahid's neighbourhood, it's easy to see why.

The maze of narrow alleyways are full of potholes, with goats grazing on piles of rubbish, kids playing on rooftops and pools of stagnant water everywhere. These are ideal conditions for the mosquitoes that carry encephalitis to breed.

Mohamed, like many of the other parents who lost children that night, was given an "ambu bag" (a manual oxygen pump) to assist Khushi with her breathing. The pumps are intended for emergency use when there is a shortage of ventilators. They are less effective for prolonged periods of time, and can be exhausting to operate.

"I don't know how to use this, how long can we go on like this pumping constantly?" Israuti Devi, who was also at the hospital that night, recalled asking a nurse as she tended to her new-born grandchild.

"If you don't pump the child will die," came the reply. The unnamed infant died the following morning.

The Baba Raghav Das Hospital, where the deaths occurred, is used to scenes of chaos at the height of the encephalitis season, usually when the monsoon rains start in August. The corridors are transformed into campsites with duvets carpeting the floor and pressure cookers whistling in the background.

Many of the deaths happened at the intensive care unit of the hospital

The poor come from afar to seek treatment here and these hallways become their home for weeks. This hospital, which caters for a population of up to 60 million, is overburdened and under-resourced.

But even given the pressures it operates under, those who witnessed the night of 10 August say it was frantic and extraordinary. Parents were seen carrying the bodies of their dead children as journalists tried to gain entry to the ward. The local media had got a tip-off that there was an apparent shortage of oxygen.

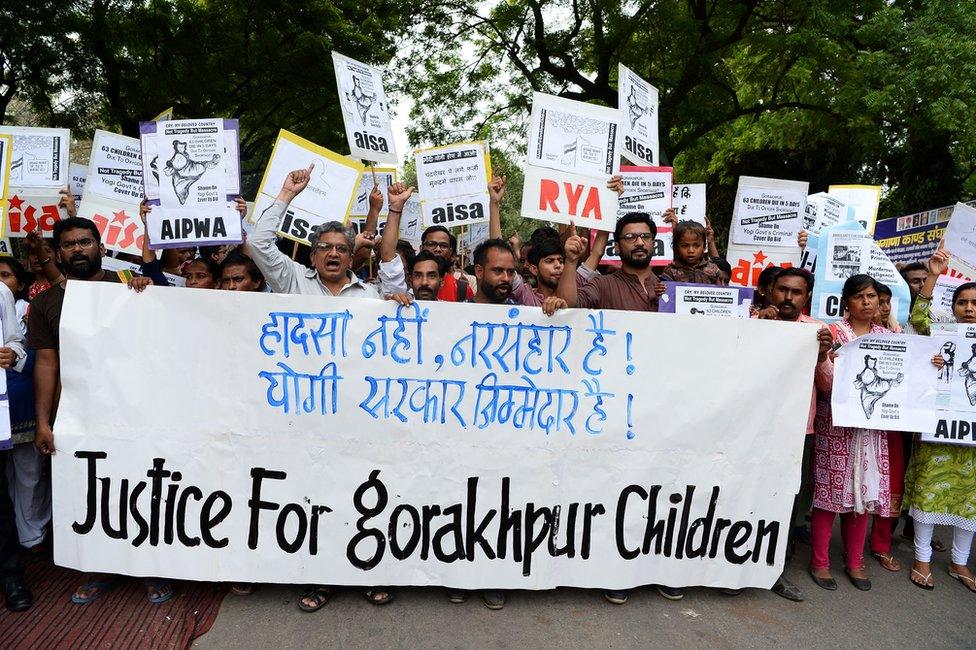

In the days that followed, there were protests on the street, debates in parliament and wall-to-wall media coverage. One account in particular, from junior doctor Kafeel Khan, was widely shared across Indian social media.

In a video, Dr Khan describes begging nearby hospitals for canisters of oxygen when he learnt that his hospital's central supply had been exhausted.

"I brought 250 cylinders in 24 hours! 250! I don't know how many children lived or died but I did my level best."

Dr Khan is now in prison, along with eight others. He is awaiting trial on charges of attempting to commit culpable homicide, a criminal breach of trust by a public servant and criminal conspiracy. His lawyer told the BBC that Dr Khan had done nothing wrong.

But, contrary to what Dr Khan said in the video, the lawyer said that the oxygen was low but never ran out - the children were simply very sick.

The lawyer was not alone in pouring cold water on the idea of a crisis last August. Some prefer not to talk about it at all, fearful of government recriminations.

Yogi Adityanath (in orange) is Uttar Pradesh's chief minister and a Hindu priest

Both the state government and the hospital administration have said that the children died from various diseases, including encephalitis.

Up until earlier this month, Gorakhpur was fertile territory for India's ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and it was the constituency of Yogi Adityanath, Uttar Pradesh's chief minister. He's a firebrand politician with a divisive past, but he is also the high priest of the city's revered Gorakhnath temple.

Gorakhpur's newfound notoriety hasn't gone down well with him. It has also become an electoral liability - a recent by-election saw the BJP lose Gorakhpur to a coalition of smaller parties. The result was unprecedented. Gorakhpur had been won five times by Mr Adityanath, external until he became the chief minister last year.

We tried to get a response from the state government. After corresponding with Mr Adityanath's office on numerous occasions over several months, they insisted no interview request was ever received.

There deaths triggered protests across the state

In the days following the tragedy, Pushpa Sales Private Limited, the hospital's oxygen supplier, provided the media with a series of letters sent to the hospital and state authorities, warning them that bills were overdue.

The company has always insisted they never cut the supply and that the letters were only a threat. The letters had been signed by Manish Bhandari, the firm's owner, who is now in jail. He was arrested in September 2017 for "breach of contract".

"We are doing business - never cheating in our family," says Mr Bhandari's father, his eyes welling up. "It is not in our blood to cheat."

We had stumbled across him after a tip-off from an elderly security guard. Nobody else was willing to tell us where the family was based.

"We pray to God: please - send him home as soon as possible. We have full faith in our judiciary."

Another man evidently moved by the events of that night is Dr Rakesh Saxena, who showed me around the dilapidated hospital, including the oxygen supply room.

"The oxygen pressure from the liquid oxygen cylinder was low, so it was switched over to emergency oxygen," he told me.

Dr Rakesh Saxena was at the hospital on the night of 10 August

But when I asked for more detail, his muffled response was telling.

"There was lot of media, lot of chaos; things were going on here and there - I don't know what happened."

Seven months on, the matter is before the courts and the media furore has quietened. Paediatric experts tell me we will never know for certain how many children died as a direct result of a shortage of oxygen. There's no knowing when or if parents will get the answers they need to fully grieve for their children.

Back at Mr Zahid's home, his wife, Rehana, takes a break from her chores to share her memories of Khushi with me. She shows me a picture of Khushi.

Mohamed Zahid also showed the picture to journalists at the time of the tragedy last year

Dressed in a black poufy dress, Khushi's eyes are defined with dark kohl to ward off evil spirits, her hair in a well-oiled side parting.

This is the only picture the family have of her.

"She was always happy, that's why we called her Khushi, which means happiness. And now she's gone so far away. I feel so empty."

You can also listen to Krupa Padhy's report on the BBC World Service.

- Published16 August 2017

- Published8 November 2011