India election 2019: The next manufacturing superpower?

- Published

In the run-up to the Indian election, which gets under way on 11 April, BBC Reality Check is examining claims and pledges made by the main political parties.

The Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has undertaken an ambitious programme to generate growth in the country's manufacturing sector.

While it's too early to pass judgement on Mr Modi's pledge, we can look at the progress made towards this goal.

Make in India

Launching the Make in India programme in September 2014, Narendra Modi promised to "raise the contribution of the manufacturing sector to 25% of GDP [gross domestic product, the total value of goods and services produced in India] by 2025".

The government said it aimed to achieve this by:

targeting specific sectors

providing support to existing companies

attracting foreign investment

But the leader of the opposition Congress party, Rahul Gandhi, has strongly criticised the programme, saying manufacturing is "not firing up" and that the plan was badly thought out.

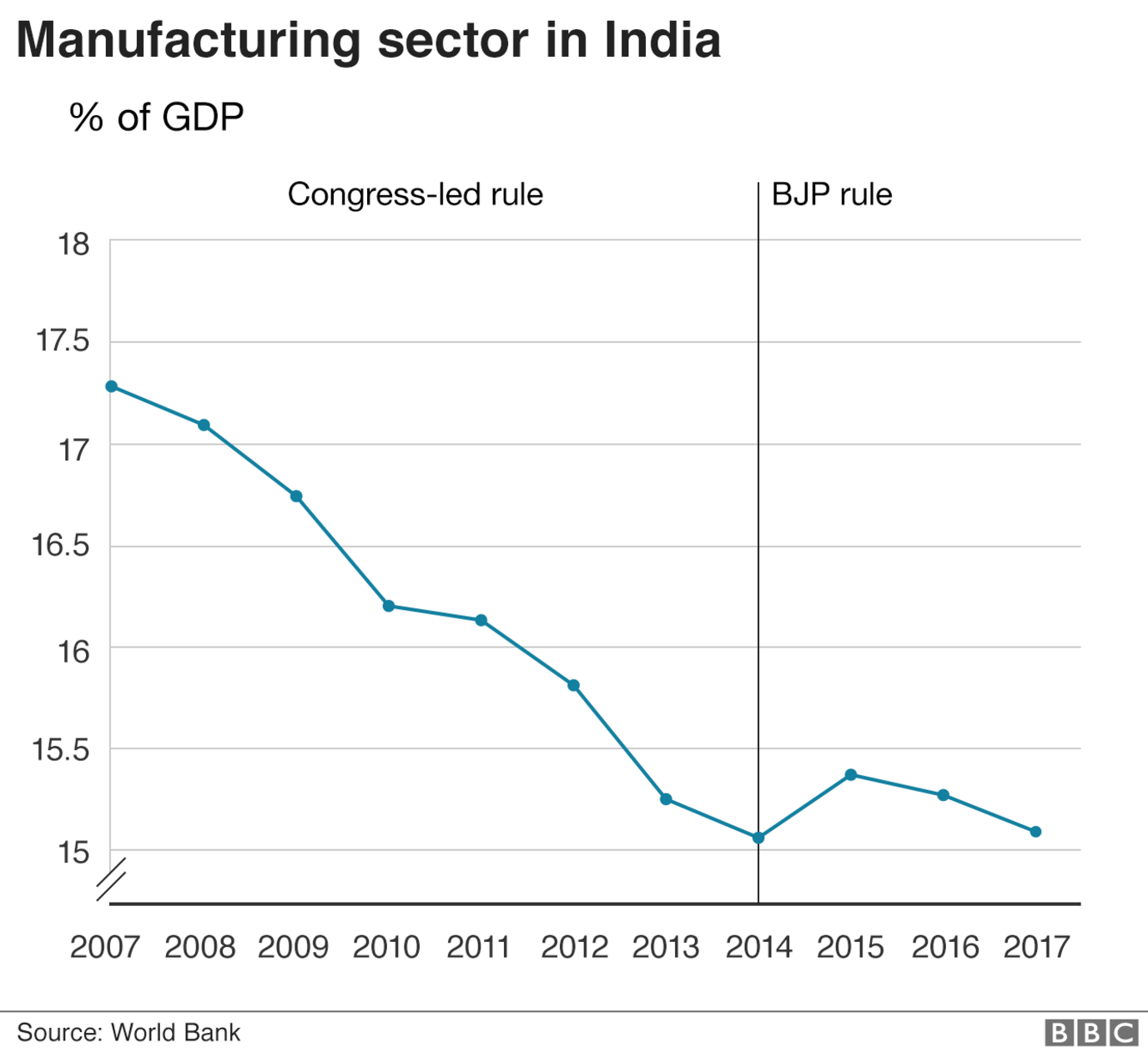

An initial look at data published by the World Bank shows the contribution of the manufacturing sector has remained just above 15% in recent years.

This is not only far short of the target but there is also little sign of an upward trend towards meeting it.

The government has been highlighting more recent data showing signs of improving industrial growth.

In a recent progress report on the Make in India project, the government points to a significant growth in manufacturing output, external over the past year.

This, however, should be seen in the context of the current economic growth rate (GDP) of about 6-7% - rather than an increasing share of manufacturing in the total.

Long-term decline

Pushing for a 25% share for manufacturing has been a familiar theme for successive governments - and one that has come nowhere near being achieved.

The share of manufacturing in the overall economy has been on a downward trend for a over two decades.

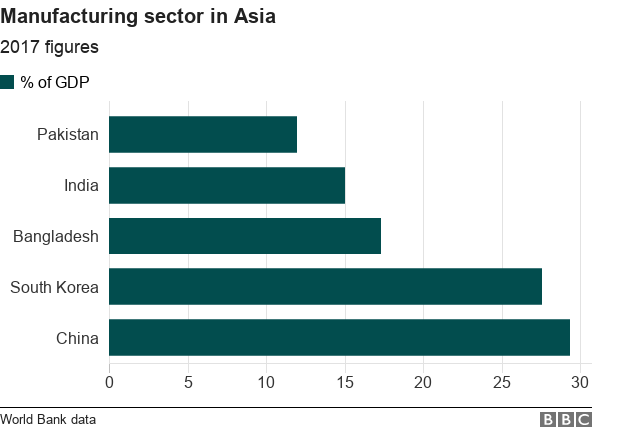

Other economies in Asia, such as China, Korea and Japan, have been more successful in achieving higher shares of manufacturing output.

China, in particular, has created large numbers of jobs in the manufacturing sector.

"It's important to remember that China started with a much more broad-based and educated workforce when it embarked on its economic transition," says Swati Dhingra, from the London School of Economics.

"India has seen mostly jobless growth in manufacturing even during boom periods - or at least a lack of secure employment arising from it," she adds.

So, if one of the aims of Make in India was to create more jobs in manufacturing, that doesn't appear to be happening.

Efforts may yet pay off

The current government does point to progress in specific sectors:

an increase in arms exports and defence equipment production

substantial investment in the biotech industry

more education and training in appropriate skills for manufacturing

the commissioning of new chemical and plastics plants

The annual World Bank Ease of Doing Business report also shows India moving up the rankings for 2018, external - a fact that's also been highlighted by the government.

And there are other encouraging signs - the automobile industry, for example, where India is emerging as a major player.

"It is unlikely that manufacturing will increase a lot in the next five to seven years," says Abhijit Mukhopadhyay, of the Observer Research Foundation.

"It takes a lot of time and sustained effort for it to be the engine of economic growth," he adds.

Nevertheless, India remains one of the fastest growing economies globally, whether or not it's powered by manufacturing.

A recent UN report has forecast that the Indian economy will grow by 7.6% in 2019 and 7.4% the following year, external, putting it ahead of other economies in the region.

- Published26 September 2018

- Published25 September 2018