India election 2019: Did the ban on high-value banknotes work?

- Published

In the run-up to the Indian election, which gets under way on 11 April, BBC Reality Check is examining claims and pledges made by the main political parties.

One of the most dramatic actions taken by the ruling BJP was the withdrawal in 2016 of all high-value banknotes from circulation, almost overnight.

This effectively removed 85% of all cash notes from the economy.

The Indian government said this was intended to flush out undeclared wealth and counterfeit money.

It also said it would help move India towards an economy less dependent on cash.

However, Reality Check has found that there's little evidence the ban has helped root out illegally held assets.

And compared with other emerging economies, the level of cash in circulation in India has remained high.

What actually happened?

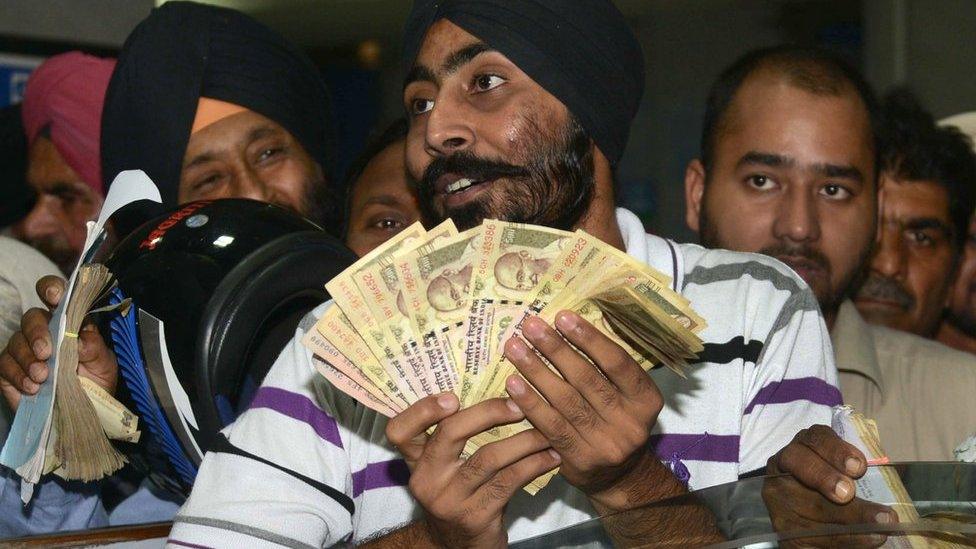

In November 2016, the two highest notes in circulation - 500 and 1,000 Indian rupees (£11) - were scrapped.

The surprise move - referred to in India as "demonetisation" - caused widespread confusion and led to street protests.

For a limited period only, the withdrawn notes could be exchanged for legal currency at banks - but there was a limit of 4,000 rupees per person.

What impact did it have?

Critics said the policy severely disrupted the economy, badly affecting the poor and rural communities that relied on cash.

The government said it was targeting illegal wealth held outside the formal economy, which fuelled corruption and other illegal activity and had not been declared for tax purposes.

It was assumed that those with large amounts of such cash would now find it difficult to exchange for legal tender.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But by August 2018, a report published by India's central bank said that more than 99% of the old banknotes in circulation prior to the ban had been accounted for.

This caused some surprise - and led to further criticism of the move.

It was suggested that there had not been much unaccounted for wealth held in cash in the first place - or if there had been, the owners had found ways to convert it to legal tender.

Did the policy achieve the objective of exposing counterfeit currency?

Not really, according to India's central bank.

The number of fake 500 and 1,000 rupee notes found after the ban was only marginally higher than the amount from the previous year.

The new notes have features designed to make them harder to counterfeit, but fake versions of these have since been discovered, according to economists at the State Bank of India., external

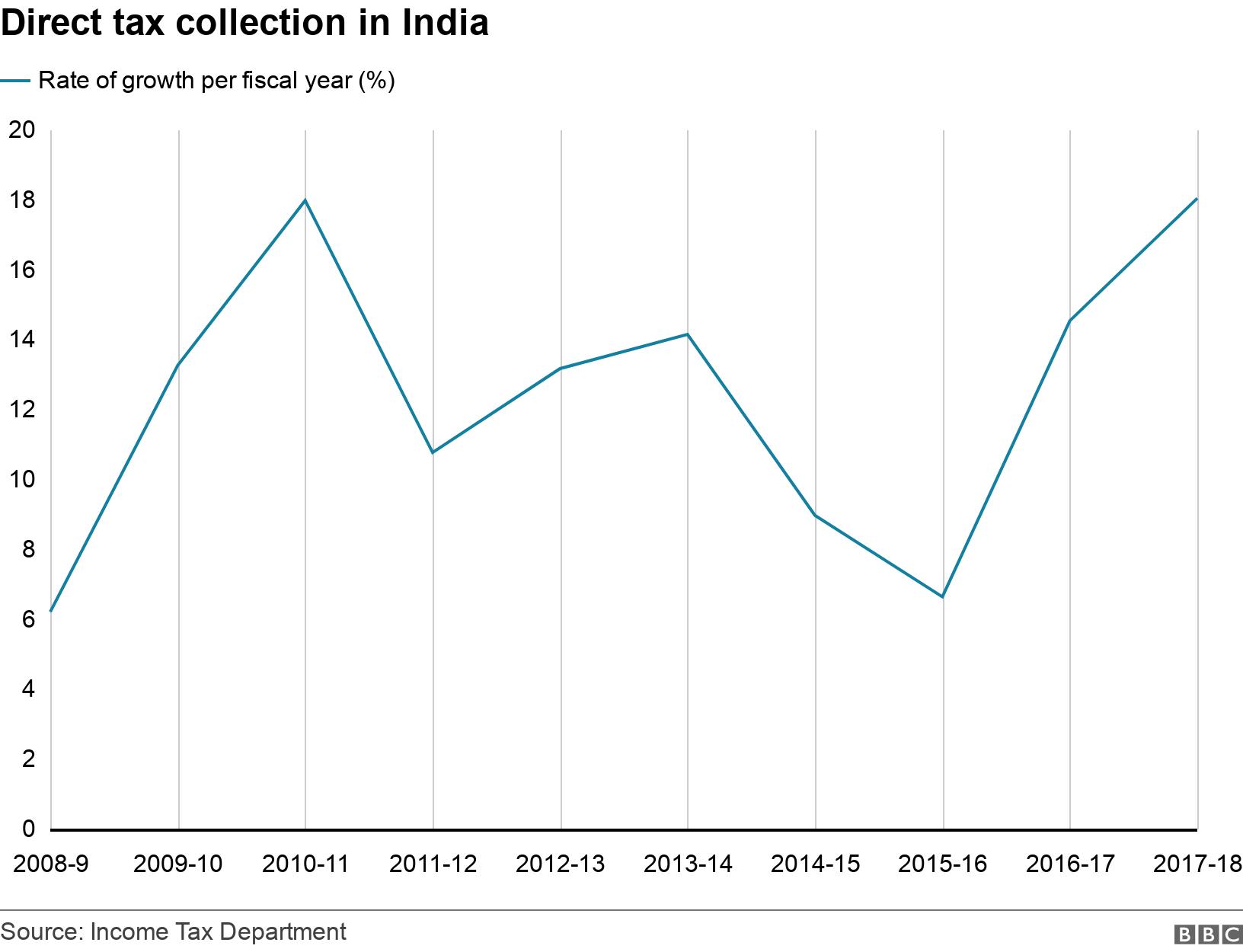

Is more tax being collected?

Another aim of the policy had been to improve India's poor record on tax collection.

The idea was that if more transactions were carried out digitally and in the open, it would be easier to enforce tax payments.

An official government report last year said the note ban had indeed resulted in an improved tax take, largely by revealing more tax evaders. , external

In the two years before the currency withdrawal, tax collection growth rates had been in single digits.

Then in 2016-17, the amount of direct taxes collected increased by 14.5% over the previous year.

The following year, collections rose by 18%.

But the rate of growth in collecting direct taxes had seen a similar increase between 2008-09 and 2010-11, when the Congress party was in power.

And it's likely that other policies - such as an income tax amnesty in 2016 and a new goods and services tax the following year - may have contributed as much to the growing tax take as demonetisation.

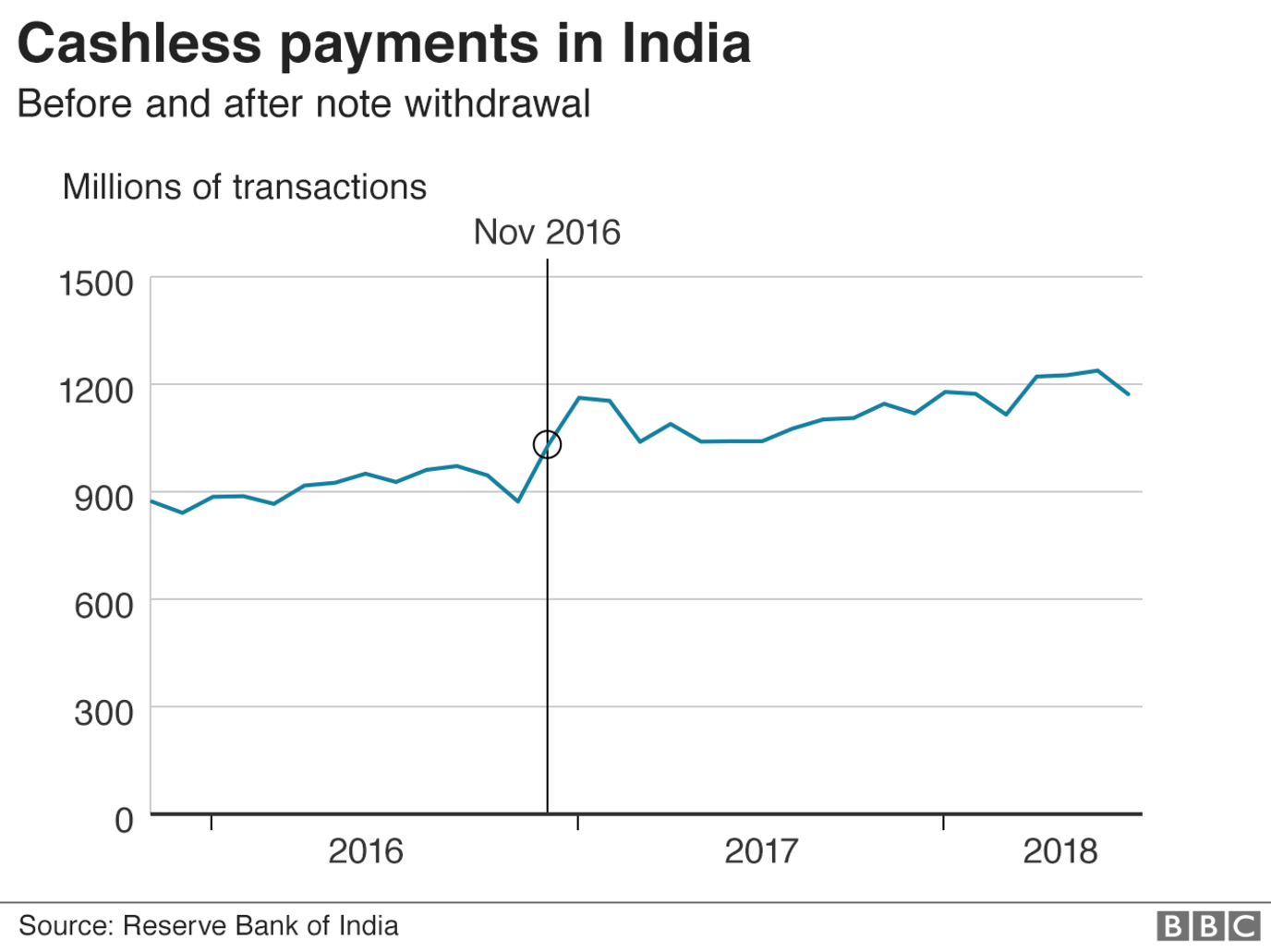

What about a cashless society?

Against a long-term trend of a gradual rise in cashless payments, there is a significant jump at the end of 2016, when the notes were withdrawn.

But this reverted soon afterwards to the steady rising trend.

The overall increase over time may have less to do with government policy and more to do with changing technology and easier cashless payments.

As to whether the overall amount of cash in the economy has fallen, we can look at India's currency to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio over time.

This is a measure of the amount of currency in circulation in proportion to the total value of goods and services produced.

This took a sharp dive immediately following the withdrawal of the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes - but by the following year, currency in circulation had reverted to pre-2016 levels.

And not only has cash usage not fallen, India also still has one of the highest levels when compared with other emerging economies, external.

- Published17 November 2016

- Published14 November 2016

- Published30 August 2017

- Published10 April 2019