Harappa grave of ancient 'couple' reveals secrets

- Published

The couple are believed to have died at the same time

About 4,500 years ago, a man and a woman were buried in a grave together in a sprawling cemetery on the outskirts of a thriving settlement of one of the world's earliest urban civilisations.

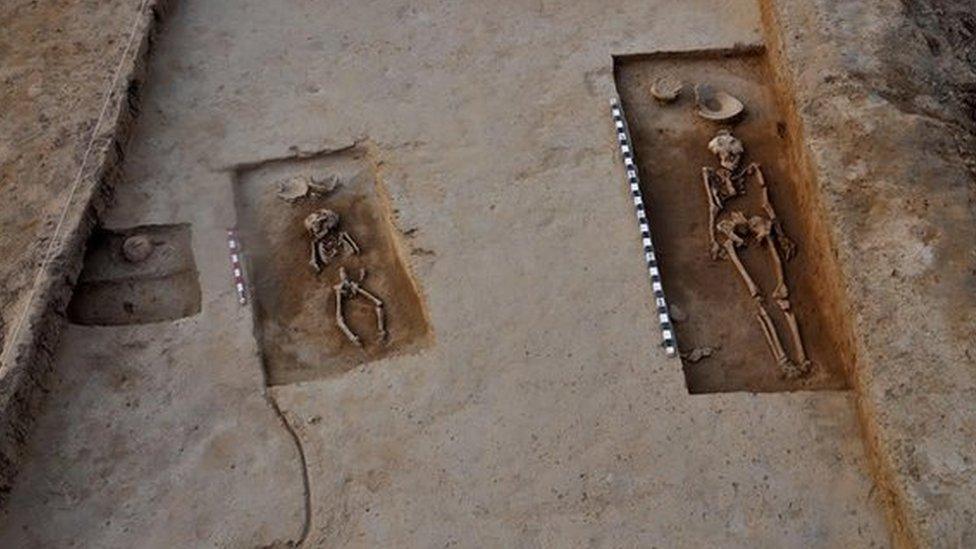

In 2016, archaeologists and scientists from India and South Korea found these two "very rare" skeletons in a Harappan (or Indus Valley) city - what is now Rakhigarhi village in the northern Indian state of Haryana. For two years, they researched the "chronology" and possible reasons behind the deaths; and the findings have now been published in a peer-reviewed international journal. , external

"The man and the woman were facing each other in a very intimate way. We believe they were a couple. And they seemed to have died at the same time. How they died, however, remains a mystery," archaeologist Vasant Shinde, who led the team, told me.

They were buried in a half-a-metre-deep sand pit. The man was around 35 years old at the time of his death, while the woman was around 25. Both were reasonably tall - he was 5.8ft (1.77m) and she, 5.6ft. They were both possibly "quite healthy" when they died - tests didn't find any lesions or lines on the bones or any "abnormal thickness" of skull bones, which could hint at injuries or diseases such as brain fever.

Scientists have excavated 40 graves in Rakhigarhi

Archaeologists say this unique "joint grave" was not an "outcome of any specific funeral customs commonly performed at that time". They believe that the man and the woman "died almost at the same time and that, therefore, they had been buried together in the same grave".

Ancient joint burial sites have always evoked interest. In a Neolithic burial site in an Italian village, archaeologists found a man and a woman in an embrace. In another joint burial reported from Russia, the couple were holding hands and facing each other. Nearly 6,000-year-old skeletons in Greece were found embracing each other, with their legs and arms interlocked.

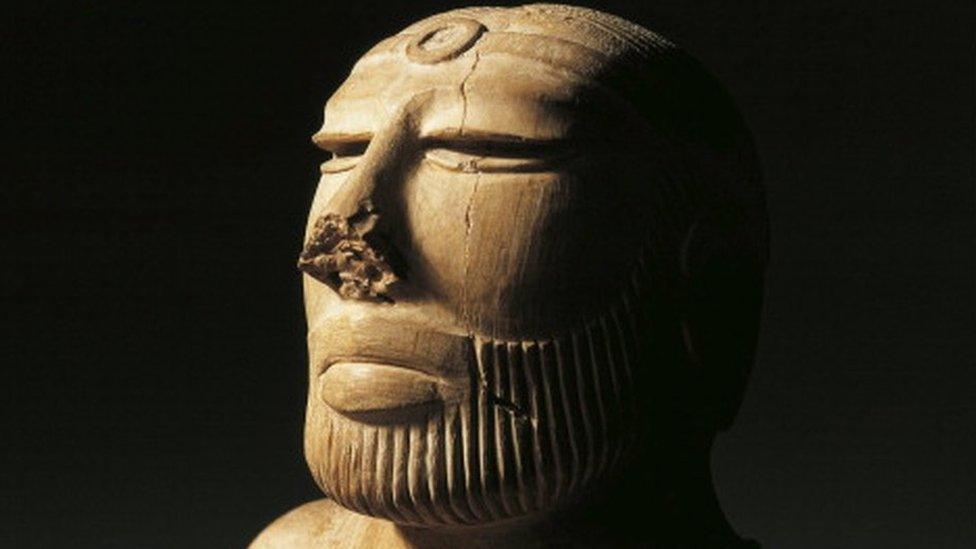

Everything else they found in the Rakhigarhi grave was unexceptional for its time: a few earthen pots and some semi-precious stone bead jewellery, commonly found in graves from the bronze age Harappan civilisation. "The most striking thing about Harappan burials is how spartan they were. They didn't have grand burials like, for example, kings in West Asia," says Tony Joseph, author of Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From.

In Mesopotamia, for example, kings were interred with hoards of precious jewellery and artefacts. Interestingly, jewellery made of carnelian, lapis lazuli and turquoise possibly exported from Harappa were found in graves in Mesopotamia.

More from Soutik:

In Harappan cities, graves usually contained pots with food and some jewellery - people likely believed in life after death and these materials were meant to be grave offerings. A lot of the pottery, says Mr Joseph, comprised lavishly painted dishes on stands and squat, bulging jars. "There was nothing remotely suggestive of royal funerals, which were common in west Asia," he adds.

Archaeologists believe the "mystery couple" lived in a settlement spread over more than 1,200 acres, housing tens of thousands of people. Of the 2,000-odd Harappan sites discovered in India and Pakistan so far, the settlement in Rakhigarhi is the largest, overtaking the more well-known city of Mohenjo Daro in Pakistan. (The ancient civilisation was first discovered at Mohenjo Daro in the 1920s.)

Archaeologists say the skeletons have been 'well preserved'

To be sure, this is not the first time archaeologists have discovered a couple in a Harappan grave.

In the 1950s, the skeletal remains of a man and a woman, heaped on top of each other, were found in a sand pit in Lothal in what is now Gujarat. The skull of the woman bore injury marks. Some excavators made a controversial claim that the grieving woman had killed herself after her husband's death - a claim that could never be proved.

At Rakhigarhi, archaeologists have discovered 70 graves in the cemetery, barely a kilometre away from the settlement, and excavated 40 of them. But this single grave of the "mystery couple" has turned to be most fascinating of all.

- Published30 December 2018

- Published28 November 2017