Is affirmative action in India becoming a gimmick?

- Published

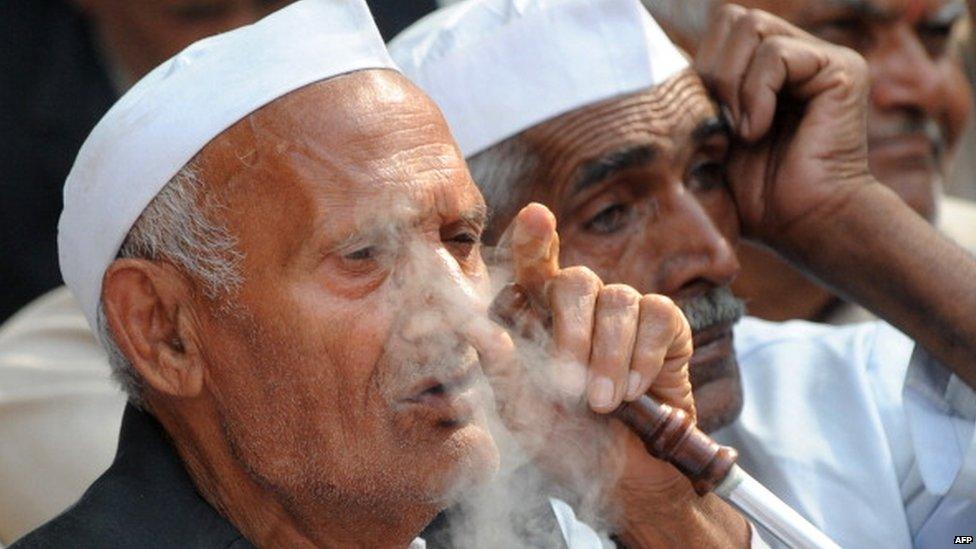

There has been a clamour for quotas among the economically weak upper castes

India's affirmative action programme is one of most comprehensive in the world.

It is built into the country's 68-year-old constitution, and reserves seats in parliament and state assemblies for the country's most socially disadvantaged groups, as well as government jobs and places in educational institutions.

"Reservations" or quotas have been given to the caste-based groups - mainly Dalits (previously known as "untouchables") and tribespeople - to rectify historical wrongs perpetrated by the country's harsh and toxic Hindu caste hierarchy. There's ample evidence to prove that these quotas have helped to empower and uplift the socially deprived.

The programme is also controversial. Identity and caste-based groups clamour for fresh quotas as formal jobs and quality education remain chronically scarce. This has forced the Supreme Court to cap reservations at 50% of the total jobs and seats. No wonder affirmative action has become a tool for politicians to win quick votes.

Earlier this week, fresh evidence of this surfaced when Prime Minister Narendra Modi's BJP-led government proposed that 10% of government jobs and seats in educational institutions should be reserved for economically-backward upper caste citizens - those who earn less than 800,000 rupees ($11,500) annually and own less than five acres of land.

Since all parties are complicit in mining caste to dole out patronage, few MPs resisted this move. A bill to amend the constitution to allow for the new quotas was passed by the lower house in a record 48 hours. The upper house passed it late on Wednesday.

The timing of the move is evidently suspect.

The BJP is facing crucial general elections in a few months. The shock defeat of the ruling party in three major states recently has energised - and united - the often fractious opposition ahead of the summer elections. Mr Modi, a charismatic campaigner and his party's prime vote-getter, no longer looks unbeatable. Formal jobs have dried up, and farmers across the country are struggling because of poor crop prices.

"This is an eleventh-hour ploy to shape a pre-election economic narrative," says Milan Vaishnav, a senior fellow and director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

India's historically deprived communities have been the main beneficiaries of quotas

It is difficult to argue otherwise. India's economy may be reasonably buoyant, but the rising tide is no longer lifting all boats. Put simply, there aren't enough jobs.

To make matters worse, the country lost 11 million jobs last year, according to a startling report by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. People in both cities and villages have been hit. Two-thirds of Indians live in villages, where the majority of the job losses have taken place. Even people belonging to politically influential, upper caste groups have fallen upon hard times.

Wooing back voters

Mr Modi's party hopes that this quota announcement will help it woo back the upper castes - traditionally the party's faithful base - who are now economically struggling because of a lack of jobs and a sluggish business environment. But, as Pratap Bhanu Mehta, vice-chancellor at Ashoka University, says, announcing a quota to tackle what is essentially a dire jobs crisis is "cynical politics, cynical policy".

Many believe it is cynical because it will be difficult for Mr Modi's government to honour this promise. For one thing, there isn't enough time to enforce it before the elections, which must be held by May. Secondly, this move may still run into legal challenges, and the top court may yet strike it down. Thirdly, it could trigger another wave of affirmative action demands from other groups like minorities and women.

India's top court in 2016 struck down a government move to reserve jobs for the powerful Jat caste

Most importantly, there aren't enough government jobs to honour the quota. There were 17 million jobs in the government in 2012, down from 19 million in 1991.

"The fact is that an increasing number of people in India are clamouring for a consistently shrinking number of government jobs. More people want a slice, but the pie is getting smaller each year. This may be good politics, but it also reflects a sense of desperation about India's jobless growth trajectory," says Mr Vaishnav.

The summer elections will prove whether it's good politics. After all, as political scientist D Shyam Babu says, Indian voters are astute. "They are very suspicious of pre-election promises of this kind".