#MeToo in India: The women left behind

- Published

Domestic maids and other women in India's informal sectors are particularly vulnerable

India's #MeToo campaign has taken off in fits and starts but it has still not touched the lives of millions of poor, vulnerable women who work in informal jobs, writes professor Sreeparna Chattopadhyay.

Meena (her name has been changed on request) is a 45-year-old domestic worker in the southern city of Bangalore. And she is a survivor of sexual harassment in the workplace.

She cooks and cleans in three different homes, earning around 6,000 rupees ($84; $64) a month. She used to earn nearly three times as much. But she lost her job in several homes after she accused one of her employers of sexually harassing her.

Meena said the harassment started after she borrowed 100,000 rupees for her older daughter's wedding from a couple in their early 70s. She had been working in their house for three years by then.

She alleged the man would initially try and brush past her while she was sweeping or mopping the floor. Sometimes, she said, he would try and touch her casually or even tug on her sari.

Scattered surveys of female workers in different parts of the country tell an incomplete but important story

His wife, Meena said, was often asleep and didn't seem to know about her husband's inappropriate behaviour.

Meena said she tried to resist his advances.

But one evening his wife locked herself in the bedroom and went to sleep. That day, she alleged, he grabbed her and tried to pull her onto the sofa.

Despite his age he was strong she said, but fortunately not stronger than her. She managed to push him away, and flee the house never to return.

Meena did not file a police complaint because she assumed no-one would believe her. But then the couple started pressurising her to return the money she had borrowed, failing which they wanted her to return to work to pay off her debt. At first, they threatened her over the phone. Then, she alleged, they sent men to her home to intimidate her.

The wife also blamed her for dressing "provocatively" and "tempting" her husband.

Given their economic and social vulnerability, informal workers are less likely to report offences against them

Meena said she was scared, depressed and did not know what to do. She could not pay off her debt in full and returning to work in their home was not an option.

In one of the other houses that she worked in, she felt comfortable enough to share her experience. This employer put her in touch with a domestic workers' union and another organisation that works on violence against women in Bangalore.

The union representative spoke to the elderly couple and threatened police action if they did not stop harassing Meena.

Meena had some money saved and decided to use it to pay off as much of the debt as she could.

Domestic workers' groups have been protesting for years for more benefits

Her tribulations ended but she still struggles. Her daughter suffers from cerebral palsy and needs constant care, so she spends a significant portion of her savings taking her to school every day because she can't walk by herself. She is entitled to a disability allowance from the government but the payments are not regular.

The incident also scarred Meena - she had nightmares, was afraid to take a job near the home of her previous employers and experienced shame and guilt.

Informal workers like Meena - women employed as domestic workers, construction labour, garment workers and vendors - make up 94% of India's female workforce. But their experiences of sexual harassment or assault rarely come to light.

And data is also hard to come by - scattered surveys of female workers in different parts of the country tell an incomplete but important story.

Read more about the #MeToo movement in India

A 2012 study by Oxfam of formal and informal workers in eight Indian cities showed that 17% of women were sexually harassed at work, external - the most vulnerable being female labourers (29%) and domestic workers (23%).

A survey of domestic workers in 2018 in and around India's capital, Delhi, , external found that 29% of them were sexually harassed at work.

These figures are low compared to studies from the formal sector where rates of reported harassment range from 88% in the BPO, external (Business Process Outsourcing) sector to 57% in the health sector.

But this is because given their economic and social vulnerability, informal workers are less likely to report offences. Even if they do, these cases may never lead to justice for the victims because they may be eventually withdrawn fearing reprisals.

Bollywood actress who began India #MeToo firestorm

There have been a few cases that have grabbed national attention.

In 2017 for instance, domestic workers and their families stormed a posh apartment complex in Delhi, external alleging that a domestic worker had been beaten up by her employers; in 2011, a Bollywood actor was convicted for raping his maid.

But these examples are few and far between.

The #MeToo movement in India, which was preceded by LoSha (a crowd sourced list of Indian male academics who allegedly harassed students or colleagues), has named several high-profile figures, including filmmakers, actors, artists and journalists.

But the face of #MeToo - both in India and globally - has been an urban, educated, articulate and privileged woman; the experiences of marginalised women are notably absent.

While some of the more critical voices have pointed to the fact that Dalit (formerly known as untouchables) women and poor women have been left out of this movement, these voices have remained on the fringe.

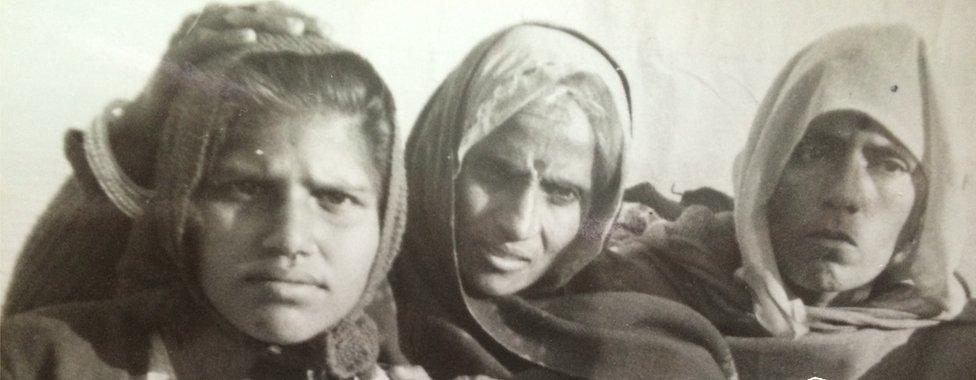

Bhanwari Devi (centre) was raped by upper caste men in 1992

This is ironic because it was the gang rape of a Dalit development worker, Bhanwari Devi, in Rajasthan state that led to India's first law against sexual harassment at the workplace.

India's sexual harassment laws mandate that in the absence of organisations, a Local Complaints Committee (LCC) headed by a district magistrate should address these complaints. But most cities or districts have no such committees.

The #MeToo movement in India has several supporters with social, economic and cultural capital and has now found a voice in mainstream media. But we are yet to see them aligning closely with informal workers' rights groups.

It is time for us to move from #MeToo to #UsAll.

Sreeparna Chattopadhyay is a senior research scientist the the Public Heath Foundation of India.

- Published17 March 2017

- Published16 December 2017

- Published23 April 2018